‘Viva Verdi!’ celebrates the joy and power of creation

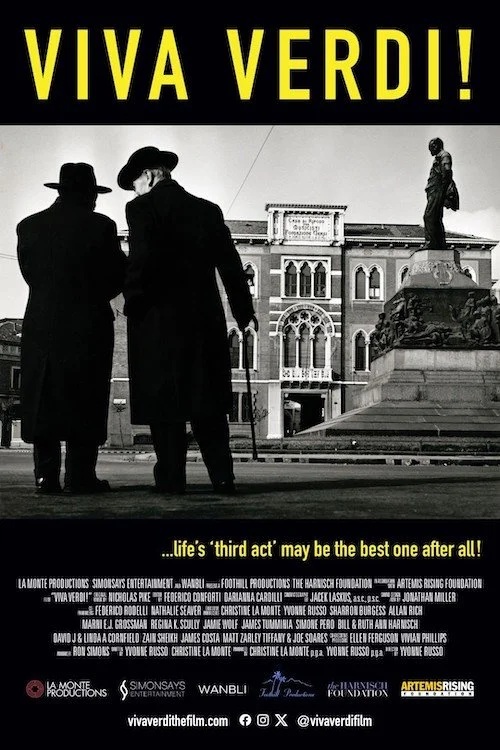

“Viva Verdi!” (2025) (Italy/USA). Cast: Claudio Giombi, Chitose Matsumoto, Tina Aliprandi, Lina Vasta, Anthony Kaplen, Leonello Bionda, Catherine Geller, Massimiliano D’Antonio, Ferdinando Dani. Director: Yvonne Russo. Screenplay: Christine La Monte and Yvonne Russo. Web site. Trailer.

One of the most inspiring messages I’ve run across in my life maintains that “The greatest joy is in creation,” a message that, ironically, came my way via a Chinese fortune cookie just as I had begun work on my first book. The timing couldn’t have been better, as this sentiment fed directly and abundantly into my writing. It proved to me at the time – and ever since – that creativity is essential to help keep us feeling young, fulfilled, prolific and vital. And, not surprisingly, that notion has also been crucial in the lives and well-being of a remarkable group of seniors who reside in a truly special retirement community in Milan, Italy, one that celebrates the joy and power of creation and what those qualities can do to help sustain – and even revitalize –.them and us. These talented individuals serve as inspiring role models not only for their peers, but also for anyone in need of rejuvenation in their lives, as illustrated in the uplifting new documentary, “Viva Verdi!”

In 1890, famed Italian composer Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901) embarked on a philanthropic undertaking that he would ultimately call his greatest accomplishment, bigger than any of the grand, legendary operas for which he became renowned. Having attained tremendous material success from his many storied works, he wanted to give something back to those who helped him attain his fame and fortune. In particular, he wanted to recognize the contributions of the musicians who brought his compositions to life, especially those who faced financial uncertainty in retirement. At the time, there were no old age pensions for retired artists, so those individuals often had no fiscal safety nets in place to protect them at a point in their lives where they likely needed assistance most.

To that end, Verdi decided to finance the construction of a retirement community for musicians in need during their golden years. But he wanted the facility to be more than just a roof over their heads. He wanted it to be a place where these musicians could live in a setting with a high quality of life, a sanctuary where residents could still be immersed in their music, both as performers for their peers and the public at large and as mentors to aspiring music students. Not only would this allow these retirees to continue to enjoy their driving passion, but it would also give them a sense of purpose and usefulness in practicing their art and in shepherding new generations of musicians into a life of enduring creativity.

Such is how Casa di Riposo per Musicisti (a.k.a. Casa Verdi) was born. Construction began in 1896 and was completed two years later, though no one occupied the facility until 1902, a year after its benefactor’s death. In its nearly 125 years of operation, Casa Verdi has been home to more than 1,000 “guests” representing practitioners of an array of musical genres, not just opera singers. Given the facility’s mission, it’s often considered a sort of “living museum,” one where the musical arts are celebrated by residents as performers and teachers while providing them with a comfortable, supportive place to call home. Today Casa Verdi houses residents aged 77 to 103, with a full range of performance and mentoring opportunities and a wide range of artistic and recreational activities, not just those specifically tied to music. In a sense, then, this geriatric artists’ sanctuary resembles the musicians’ retirement community depicted in the narrative feature “Quartet” (2012), a haven that provides more than just basic shelter.

Casa Verdi has thus more than lived up to its multifaceted mission. It has provided its residents with a venue in which they are made to feel vital as artists and instructors. They’re able to enjoy their craft and the company of their peers and to share their talents with appreciative followers while not having to worry about their material needs. Those are important considerations for individuals at this stage of life, to make the most of what time they have left, especially in the face of the ever-present conditions of declining physical and mental health. This is an inescapable fact of life for residents, as evidenced by the passing of some of those profiled in this offering who have passed on since filming on the production finished. Nevertheless, Casa Verdi has given – and continues to give – its live-in guests what they need most at a time when those needs are arguably greatest.

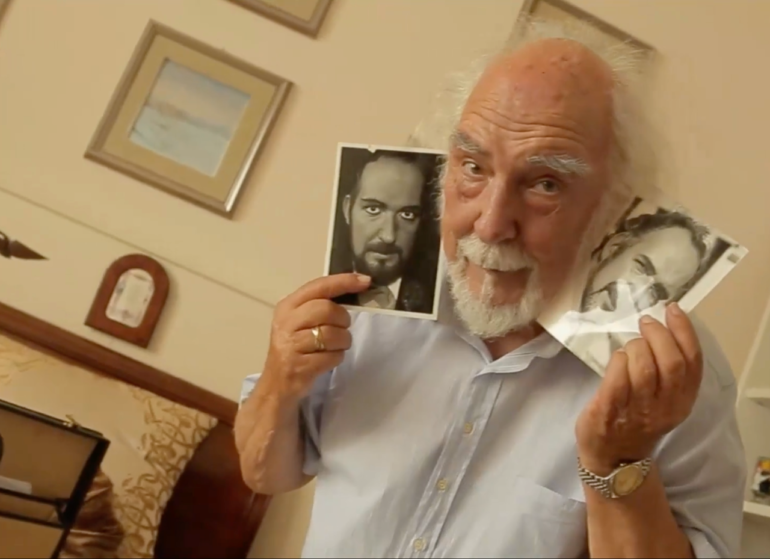

Writer-director Yvonne Russo delivers an engaging and intimate portrait of this inspirational venue. In addition to depicting the diversity and richness of daily life in this facility, the film profiles a cross-section of its colorful residents, such as eccentric, jovial baritone Claudio Giombi, one of Casa Verdi’s more prominent residents and a mentor to aspiring musicians like tenor Massimiliano D’Antonio; pianist and soprano Chitose Matsumoto, a transplant from Tokyo who relocated to Milan to learn how to sing Italian opera in hopes of enabling her to expand her repertoire beyond just performances of Giacomo Puccini’s Madame Butterfly; jazz drummer Leonello Biondi, who, at age 77, describes himself as one of the facility’s “kids”; 91-year-old violinist Tina Aliprandi, who still handles a bow as skillfully and fiercely as someone many years her junior; and soprano Lina Vasta, who describes herself as “ageless” and sports an impressive vocal range as a performer and singing coach. Viewers hear their captivating stories while learning much about their outlook on life, the value of art and music, and the importance of places like Casa Verdi.

None of this would have been possible, however, were it not for the vision of someone like Maestro Verdi himself. He was able to picture the founding of a facility such as this at a time when they were virtually nonexistent and the beneficiaries of his generosity were typically (and unceremoniously) left to go without. However, he believed in the possibility of being able to establish a sanctuary like this and to enable bringing it into being. That was quite an accomplishment for the time, but it also set in motion a movement that helped to make comparable facilities more of a reality in subsequent years.

The key in making this happen is attributable to Verdi’s beliefs, for they play a central role in the manifestation of one’s existence, a product of the conscious creation process, the philosophy that makes such outcomes possible. It’s unlikely that Verdi ever heard of this school of thought, but, based on what he achieved, it’s apparent that he had a grasp of its inherent principles to make things happen, particularly those of a nature that pushes the envelope of conventional thinking and perceived limitations. That’s worth noting for anyone looking to try the untried, to transform intangible concepts into tangible results, especially where they enable the fulfillment of needs that have gone unaddressed.

Verdi’s vision clearly operated on multiple levels. His beliefs in founding this facility helped to meet the practical, everyday needs of its residents for their material considerations, as well as facilitating access to the means for their continued artistic fulfillment. It also provided them with an outlet to further the education of budding musicians, enabling the perpetuation of their art in a new generation of performers. And, as for the performance aspect of Casa Verdi, it gave the public a venue where they could enjoy the talents of its residents. Consequently, the concurrent emergence of these various materializations illustrates the power of effective collaboration, of a shared co-creation in which the manifesting beliefs of all of its participating parties work together to contribute to the realization of this finished outcome. Indeed, in a scenario like this, it’s easy to see how everyone wins.

The specifics of the underlying beliefs behind a venture like this play a crucial role in the customized nature of the final product. For example, as noted in the film, at one point during Casa Verdi’s planning, the composer noted that an architect’s drawing referred to the facility as “a nursing home,” a label to which he strongly objected. “Nursing home,” he observed, implied a place for those in ill health, a conception decidedly not in line with his vision. Verdi insisted that it instead be termed “a retirement home,” one that carried connotations beyond infirmity. In his view, Casa Verdi was to be a place where residents could enjoy their sunset years, a time characterized by robust health, artistic fulfillment and personal satisfaction, not a place where one simply goes to die.

In line with that thinking, Casa Verdi has come to be place that puts tremendous emphasis on personal well-being, the idea that it’s a place where one can promote sound mental and physical health, with art and music playing a key role in attaining that goal. According to Managing Director Ferdinando Dani, that’s an especially important consideration in a facility where a number of residents are afflicted with conditions like Alzheimer’s Disease and other forms of dementia. To that end, then, Casa Verdi has become an ardent supporter and practitioner of treatment programs like music therapy, an initiative aimed at bolstering residents’ cognitive abilities through the intentional repetition of tonal patterns that help to promote familiarity, recognition and retention. It’s a treatment perfectly suited to musicians, who are naturally accustomed to recognizing such recurring patterns, not to mention one that they find enjoyable, too, particularly when employed in groups. It’s also another example of a creation made tangible by beliefs in the possibility of expanding limits and bringing them into being.

Given how long Casa Verdi has been in existence and the impressive results it has achieved, it’s a testament to its founder’s vision, one that has materialized in multiple ways and for multiple generations, including with significant intergenerational impact. To a great degree, this is attributable to the combined, collaborative beliefs of so many individuals operating in so many different but complementary and coordinated regards, yet another example of an effectively implemented co-creation. To be sure, not everyone involved in this venture may recognize their connections to one another in this joint effort, but they have nonetheless played valuable synchronized roles in a scenario driven by the concept of value fulfillment, the principle of being one’s best, truest self for the betterment of oneself and those around us, in this case on a collective basis. It’s a truly inspiring and uplifting idea that, in principle, could be put to use in countless undertakings if we were to put our minds to them. Imagine what it might be like to live life in a world where that approach was applied to more aspects of our everyday existence than in just isolated examples such as this. We might all lead more meaningful, enjoyable and fulfilling lives than many of us do now. Maybe more of us should consider looking to the maestro’s wisdom, insight and vision to help set us on the right course.

Casa Verdi is indeed a noteworthy facility, one that pursues – and meets – a variety of goals, one that simultaneously supports the arts and the well-being of its in-house practitioners. At a time when many of the elderly peers of these individuals might otherwise be winding down and withdrawing from life, Casa Verdi enables its residents to feel useful, inspired, and, above all, youthful (age notwithstanding). In this captivating documentary, the filmmaker takes viewers inside this artistic sanctuary, showing how it has imbued its musical family with a sense of renewal. And, in so doing, the facility thus validates the sentiment noted at the outset above, particularly for those approaching the end of their lives, giving them purpose and joy for the time they have left, especially when it comes to that all-important notion.

Because of Casa Verdi’s success in these endeavors, this cinematic chronicle of that effort makes “Viva Verdi!” one of the most uplifting pictures that I have seen in some time. In fact, if I had any complaint at all, it would be that I wish it had been longer than its 1:18:00 runtime. The residents’ stories and performances (both archival and in the film itself) are rich, colorful and fulfilling, brimming with a sense of genuine pride and pleasure, rewarding experiences that have given them (and, by extension, us) tremendous satisfaction, enjoyment and fulfillment. The picture has even earned an Oscar nomination for best original song, “Sweet Dreams of Joy,” a moving piece written by composer Nicholas Pike and performed by soprano Ana María Martinez, which can be heard playing over the closing credits. The film is available for streaming online.

Fans of opera and fine arts truly owe much to the creatives featured in this film. But they and we also need to thank Maestro Verdi for his foresight and generosity in founding the institution that so deservingly bears his name, helping to make the musicians’ final years among the best of their lives, a third act truly worth living for. We can only hope that all of us end up being just as fortunate, especially when it comes to understanding what makes life worth living – and just how true the greatest joy really is in creation.

Copyright © 2026, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.