‘The Sessions’ probes the beliefs underlying sexuality

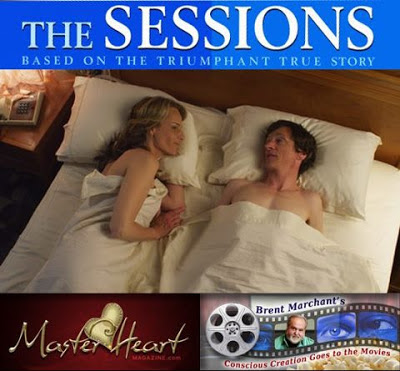

“The Sessions” (2012). Cast: John Hawkes, Helen Hunt, William H. Macy, Adam Arkin, Moon Bloodgood, Annika Marks, Rhea Perlman, Robin Weigert, W. Earl Brown, Blake Lindsley, Ming Lo, Rusty Schwimmer, Jennifer Kumiyama. Director: Ben Lewin. Screenplay: Ben Lewin. Source Material: Mark O’Brien, “On Seeing a Sex Surrogate,” The Sun magazine. Website. Trailer.

It’s been said “We are what we eat,” an observation that frequently proves right on the money. But, in my experience, I’ve found that we often are everything we do in our lives, especially the acts that comprise a part of our existence that many of us are averse to talk about, sex. Yet, if we’re truly honest with ourselves, we’re likely to find that we indeed are what we do sexually. So imagine what it must be like for someone who’s living a life without it – what would that say about him? And what would it say about him once he finally has the opportunity to experience it? Such is the odyssey of a disabled, middle-aged virgin who finally has the chance to come of age in the touching, fact-based story of “The Sessions.”

Mark O’Brien (John Hawkes) lives a life most people would probably find discouraging. As a childhood polio victim who defied the odds and grew into adulthood, he has no use of his limbs, spends most of his time confined to an iron lung and requires nearly constant care. But, despite these limitations, Mark has not allowed his disabilities to deter him from living his life. He earned his college degree from the University of California, Berkeley, becoming a writer, poet and advocate for the disabled.

However, his academic and career accomplishments notwithstanding, Mark’s life has been anything but typical. Many of the things that we take for granted simply aren’t part of his everyday existence, and this is perhaps most apparent in an area many of us would consider significant – sex. At age 38, he’s never experienced anything even remotely approaching a sexual encounter, and, with his longevity increasingly in question (given the nature of his condition and his advancing age), it’s an area he’d like to explore while he still has the chance.

Mark’s physical state, by itself, makes this prospect a challenging proposition; the logistics alone are indeed problematic. But, if that weren’t enough, Mark’s desire to explore this uncharted part of his life is further complicated by the conflicted beliefs he holds about sex, thanks mostly to his devout Roman Catholic upbringing. He’s so uncertain about how to proceed that, before he even begins examining his options, he consults his parish priest, Father Brendan (William H. Macy), for guidance.

One might question the wisdom of seeking advice on a subject from someone who’s likely to be just as clueless about it as the inquirer is. But that issue quickly proves irrelevant. Through their many conversations, Mark and Father Brendan develop a rapport more like friends than like priest and parishioner, even though their discussion topics involve profound questions of personal morality and spirituality. For instance, Mark expresses sincere trepidation about his desire to explore sexuality outside of marriage, a cardinal prohibition of traditional Catholicism and, allegedly, the word of God. At the same time, he also freely admits to a belief that God has a “wicked sense of humor,” one that he envisions typified by such images as a Heavenly Father chortling over his trials and tribulations at reconciling the challenge foisted upon him. So, when Mark finally asks Father Brendan how he should proceed, the kindly vicar says reflectively, “Given your circumstances, I think He’d give you a pass on this one.” And so, with that “blessing,” Mark begins investigating his options.

After several false starts at initiating a sex life, such as with one of his caregivers, Amanda (Annika Marks), Mark finally decides to engage the services of a sexual surrogate, Cheryl Cohen-Greene (Helen Hunt). Their sessions together, though definitely sexual in nature, are intended to be educational and therapeutic, not tawdry or lascivious. Because Mark has never experienced much in the way of physical touch, let alone physical touch of an erotic nature, Cheryl focuses on issues of body awareness, teaching him about sensations with which he’s largely unacquainted. She also coaches him about what it’s like to interact with a partner. And, through it all, she approaches her work with a curious mixture of professional detachment and intimate, though not necessarily personal, involvement, a practice that often involves precariously walking a very fine line.

Through their sessions, which are limited to six meetings (a professional standard meant to distinguish the services of a surrogate from those of a prostitute), Mark comes to learn what pleases him and what it takes to please a woman. And he definitely enjoys the sessions, no matter how unintentionally “abbreviated” they might be. Over time, though, he grows more accustomed to and comfortable with the sensations and the experience. In fact, sex even becomes quite revelatory for him, especially as he becomes more intimately acquainted with the feelings associated with the experience. But the awakenings that come out of these sessions are anything but one-sided; as the student learns from the teacher, so, too, does the teacher learn from the student, an unexpected development that stuns even the seasoned instructor. The experience ultimately changes everyone in profound and unexpected ways – and forever.

As with any experience that’s part of our reality, there are beliefs driving what we manifest. This cornerstone principle of the conscious creation process underlies all aspects of our existence, from the environment in which we dwell to the people with whom we interact to all of the activities in which we engage – even sex. The idea that this act can be reduced to purely a mechanistic operation or animalistic urge fails to recognize that it, too, arises from underlying beliefs that impel its manifestation from the realm of potential into the world of the physically expressed.

How that experience unfolds, of course, depends on the beliefs in question, and they often involve factors that go beyond one’s preferences for superficial physical considerations like gender and body type. It often includes less tangible, less recognizable qualities, such as one’s own self-image, expectations and limitations, elements that frequently do more to define the nature of the materialized sexual experience than anything having to do with partiality for a particular shade of hair color or physique.

These considerations become apparent in both protagonists’ experiences. For instance, someone in Mark’s circumstances might easily look upon his personal physical limitations as an insurmountable hindrance to enjoying a sex life of any kind, let alone a fulfilling one. The same could be said of the religious notions he wrestles with, those self-imposed, guilt-driven barriers that could easily derail one’s path to pleasure. On some level, though, Mark obviously believes otherwise; if he didn’t, he would not have been able to manifest the experiences he ultimately encounters, both during his time with Cheryl and in his life thereafter. In large part, this becomes possible as a result of his beliefs associated with, first, genuinely accepting his circumstances and, subsequently, envisioning their transcendence, moving past his initial creation to one greater than what he initially materialized. He uses his powers of conscious creation to plug the gaps in his reality, filling in the missing pieces that allow him to actually experience what might otherwise remain merely a vision. This is truly significant personal growth, and its relevance in the sexual arena is just as valid as in any other area of one’s life.

Interestingly, though, Mark is not the only one to experience such transcendence. Cheryl goes through her own transformation as well, thanks to unexpected developments in her dealings with Mark. As someone who has long managed to skillfully maneuver the razor’s edge separating professional distance from personal engagement, Cheryl initially handles her involvement with Mark as she would with any other client. But, as time passes and she begins to see the effect she’s having on him, she begins to shift her own beliefs, coming to appreciate the impact of what she’s now enabling for him, allowing herself to receive the feelings he so freely gives her and, perhaps most importantly, letting her own personal emotions regarding a client to surface for the first time. Suddenly, her work seems less clinical, more heartfelt, than she’s ever experienced before, a development that impacts her not only professionally, but also personally.

In the end, then, our sexual experiences are as much a product of who we are and what beliefs we hold as they are of any particular preferences we have or any particular acts in which we engage, and the evolution of Mark’s and Cheryl’s beliefs bears this out. The better the handle we have on what beliefs we hold, the more conscious we’ll be of the experiences they yield and the degree of pleasure that we get out of them. Such awareness will also allow us to make whatever adjustments we deem necessary to improve the quality of eroticism we enjoy. The richness and fulfillment to come out of these experiences thus serve as some of the best examples of the joy and power inherent in the act of creation.

“The Sessions” is arguably one of the best, and thus far most underrated, offerings of this year’s awards season films. It exceeded my expectations by a long shot, skillfully telling a story that’s simultaneously heartfelt, touching and wickedly funny. It’s also one of those unusual pictures that starts out well and gets better as it goes along (how often does one see something like that these days?). The performances by Hawkes and Hunt are exemplary, perhaps the best work each of them has ever done, and both have to be considered highly viable awards contenders. The writing, editing and direction are top-notch, too, making for a very cohesive overall package.

Two cautions are in order, however. First, don’t be deceived by the movie’s promotional trailer; it paints a somewhat misleading picture of the film, making it look like a high-end sex comedy, which, despite ample humor, it clearly is not (and, regrettably, sells the movie short). Second, the film is very sexually explicit, with frequent nudity and unabashed discussion and depiction of sexual topics; those who are sensitive to these issues or are easily offended should clearly avoid this picture.

A rewarding sex life has the potential to show us much about ourselves, yet all too often we allow personal or philosophical limitations to get in the way, keeping us from enjoying the experience and perhaps even preventing us from discovering unknown parts of ourselves. “The Sessions” illustrates the significance of this – the value of breaking through such barriers, of finding our own personal uncharted territories and of exploring the resplendent beauty within them. Indeed, making time for “sessions,” be they those depicted in this movie or those of your own creation, is undoubtedly time well spent.

Photo courtesy of Fox Searchlight Pictures.

Copyright © 2012, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

Leave A Comment