‘Life Itself’: Ode to a cinematic game changer

“Life Itself” (2014). Cast: Roger Ebert, Chaz Ebert, Gene Siskel (archive footage), Martin Scorsese, Errol Morris, Werner Herzog, Ramin Bahrani, Greg Nava, Ava Duvernay, A.O. Scott, Richard Corliss, Jonathan Rosenbaum, Marlene Iglitzen, Thea Flaum, Nancy De Los Santos, Roger Simon, John McHugh, Stephen Stanton (voice). Director: Steve James. Book: Life Itself: A Memoir, Roger Ebert. Web site. Trailer.

It’s a rare occasion when someone comes along who ends up being a genuine game changer in his or her particular field of endeavor. But, when such individuals make their presence felt, they leave an indelible mark on their craft, changing it forever. In the field of film criticism, that distinction belongs to Roger Ebert (1942-2013), who almost single-handedly altered the way we look at movies and whose storied life is now the subject of the engaging new documentary, “Life Itself.”

Based on Ebert’s autobiography, director Steve James’s documentary chronicles his subject’s life story from his teenage years as neighborhood reporter for a self-published newspaper to his acclaimed career as America’s top movie critic to his heartbreaking yet ever-hopeful battle against terminal cancer. In presenting Roger’s story, James serves up a wealth of archival material, coupled with narrated segments from Ebert’s memoir, interviews with family, friends and colleagues, and candid footage of the difficulties his subject faced in his final days. The result is a remarkable and surprisingly forthright depiction of Ebert’s life, something he insisted on before agreeing to be involved in the project.

Ebert’s contributions to the field of film criticism are almost too numerous to mention. His 46-year career included positions as Chicago Sun-Times movie critic, as co-host of several TV series (most notably Sneak Previews, At the Movies and Siskel & Ebert & The Movies) and as the author of numerous books. He was also a regular presenter about cinema at the Conference on World Affairs and even co-wrote the screenplay for the Russ Meyer cult classic “Beyond the Valley of the Dolls” (1970). And his efforts didn’t go unnoticed, either. In 1975, he won the Pulitzer Prize for Criticism, the first film critic ever to receive this prestigious award. Then, in 2005, he was honored again, this time with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, the only film critic ever so recognized. (Not bad for a middle-class kid from Urbana, Illinois.)

Film critics Roger Ebert (right) and Gene Siskel (left) take on one another during one of their many televised movie review duels in director Steve James’s engaging new documentary, “Life Itself.” Photo by Kevin Horan, courtesy of Magnolia Pictures.

While the picture covers the entire spectrum of Ebert’s career, much of it examines his famous (some might say infamous) relationship with film critic Gene Siskel (1946-1999) of The Chicago Tribune. As rivals at Chicago’s two daily newspapers, they initially vied for the attention of the Windy City’s moviegoing public. But that was just the beginning. The duo would later go on to host the aforementioned TV series, which often featured spirited – sometimes downright nasty – debates about current film releases. Their colorful arguments made for great television, but those disagreements (and the shows themselves) also changed the way movie lovers viewed the cinematic landscape. They brought film criticism out of the pages of the newspaper and made it more available to a wider audience. In doing so, they became the best known (and some would say most influential) film critics in America, as well as celebrities in their own right. Yet, for all the fame and fortune they built together, they never much cared for one another, their contentious rivalry characterizing much of the nature of their relationship (some of which becomes plainly apparent in outtakes from promos for their TV series and in interviews with Siskel’s widow, Marlene Iglitzen, and several of their shows’ producers).

The film also focuses heavily on the other significant relationship in Ebert’s life, that of his marriage to his wife, Chaz. Roger met Chaz late in life after years of dating women who, according to some of his friends, were of “questionable character.” But Chaz changed Roger’s life, introducing him to the love that always eluded him in his younger years. She would prove to be his rock in his waning days, too, remaining loyal and upbeat through all of his travails, which were much more taxing than most people knew, despite his very public presence almost right up until the end.

But what’s perhaps most illuminating about this film is its portrayal of the relationship Roger had with himself. He was very much in touch with who he was and how his life unfolded. In fact, he believed that we each compose the script of our own lives, that they’re like our own personal movies in which we’re actor, director and screenwriter all rolled into one. And, even though he was quite outspoken in his criticism of alternative life philosophies (such as New Age thought), his own outlook nevertheless seems remarkably consistent with the principles of conscious creation, the notion that we create our own reality with our thoughts, beliefs and intents. Some might argue that there are discrepancies between his views and those who practice conscious creation, but, in my opinion, I believe any such differences are mostly semantic, particularly given the similarities in the outcomes that each outlook propounds to evoke.

The creations Ebert materialized were quite impressive, to say the least. For instance, through his TV series, he brought film criticism to the masses, and, in doing so, he made it accessible to those who may have previously seen the subject as too high-brow or aloof. In fact, he was so successful at this that industry insiders were initially reluctant to embrace these shows (or even to measure their impact) simply because they were hosted by “Midwestern” film critics, presenters viewed as folksy rubes who couldn’t possibly possess the sophistication and clout of New York or Los Angeles critics like Pauline Kael. How wrong the detractors were, especially when the shows took off and became hits in the ratings.

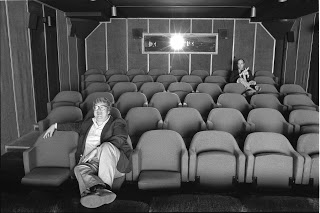

Film critics Roger Ebert (left) and Gene Siskel (right) screen a picture for review in director Steve James’s “Life Itself.” Photo by Kevin Horan, courtesy of Magnolia Pictures.

By broadening the audience for serious film criticism, Ebert also helped to broaden the profession itself. This is most evident on his web site, www.rogerebert.com, which became his “voice” after his cancerous lower jaw was surgically removed and left him unable to speak. But, in addition to providing a venue for Ebert’s output, the site also became a platform for upcoming film critics whose words might not otherwise have been given voice. By mentoring a new generation of reviewers, Roger furthered the reach of his calling and those who would take up the gauntlet in his wake. His efforts in this regard are praised in the film, too, in interviews with fellow critics like A.O. Scott and Richard Corliss.

Roger’s generosity of spirit was apparent not only in the nurturing of new critics, but also in the development of new cinematic talent. Throughout his career, Ebert was famous for giving press to the works of aspiring or little-known directors, such as Martin Scorsese, Errol Morris, Werner Herzog, Ramin Bahrani, Greg Nava and Ava Duvernay, all of whom are interviewed in the film. He was instrumental in helping to make their careers, something that benefitted both those artists and the moviegoing public.

However, despite Ebert’s willingness to support the works of up-and-coming directors (and even to befriend them in some cases), he maintained a scrupulous degree of integrity when it came to assessing their pictures. Scorsese, for example, discusses Ebert’s harsh (and disheartening) criticism of his film “The Color of Money” (1986). Despite four Academy Award nominations (including a best actor win for Paul Newman), Ebert tore into his friend’s picture. Scorsese confesses that he was disappointed at the time, but he also admits how he later recognized that Ebert’s criticisms helped make him a better filmmaker, a “gift” that would prove valuable in his future projects. In being honest, Ebert may have ruffled some feathers in the short run, but his wisdom subsequently helped elevate the art form he so loved, another of his inspired creations, to be sure.

But, for all his professional accomplishments, his personal triumphs were amazing achievements as well. Just ask Chaz and her family, many of whom are interviewed in the film and serve as a topic of discussion in voiceover narrations from Roger’s memoir. Through them, he built a family for himself. And that accomplishment, as fulfilling as it was, wouldn’t have happened if it hadn’t been for another of his achievements – kicking the drinking habit – for it was through his association with Alcoholics Anonymous that he would meet his future bride (and everything that came with that). Indeed, to paraphrase Clarence, the lovable guardian angel from Frank Capra’s legendary Christmas classic, “Roger, you’ve truly had a wonderful life.” And, fortunately for Roger, he recognized this, too, regardless of whatever difficulties may have graced his path along the way.

Film critic Roger Ebert (right) and the love of his life, Chaz (left), smile for the cameras on their wedding day in the engaging new documentary, “Life Itself.” Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures.

“Life Itself” paints a beautiful portrait of a towering figure, and it does so with sequences that are both heartbreaking and heartwarming. Its selection of archive, interview and recent footage tells a balanced, frank and compelling story, warts and all. There are both ample laughs and touching moments, as well as film clips from many of Ebert’s favorite movies, all combining to create one of the most complete pictures I’ve seen in quite a long time. The film is a sure-fire contender in the documentary categories for this year’s awards competitions.

As a longtime Chicago resident, I became well-acquainted with Roger Ebert over the years through his work as a critic for the Sun-Times, a movie reviewer for the local ABC-TV affiliate and as a co-host of Sneak Previews, the PBS series produced by the network’s Chicago affiliate, WTTW. But, beyond his published and broadcast works, I came to admire Roger’s approach to film criticism, one that was thought-provoking but that never went beyond the audience’s comprehension. And, just as Roger saw himself as the creator of the movie of his own life, I frequently offer comparable observations in my own writings – but, then, I had a good source of inspiration to draw from.

Roger Ebert left an incredible mark on an industry, an art form, even the nation’s culture. He helped transform a casual pastime into something more, something that both entertains and enlightens but that also maintains a certain familiarity we can all relate to. That’s quite an accomplishment, one for which all moviegoers should be grateful.

Take a bow, Roger.

Copyright © 2014, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

Leave A Comment