‘Eternal Beauty’ sheds light on the search for ‘normal’

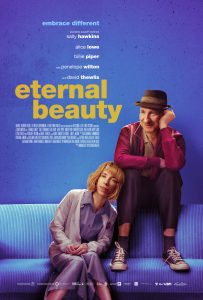

“Eternal Beauty” (2019 production, 2020 release). Cast: Sally Hawkins, David Thewlis, Penelope Wilton, Billie Piper, Morfydd Clark, Alice Lowe, Paul Hilton, Spencer Deere, Robert Pugh, Natalie O’Neill, Elysia Welch, Boyd Clack, Rita Bernard-Shaw, Robert Aramayo (voice), Nicholas Lumley. Director: Craig Roberts. Screenplay: Craig Roberts. Web site. Trailer.

Throughout our lives, we’re often bombarded by statements, observations and criticisms associated with what constitutes “normal.” But what is that exactly? It’s often considered something ordinary and everyday, yet it frequently gets elevated to a standard that’s essentially unattainable, prompting us to wonder what good it would be then. Finding our way through such a perplexing maze can become a challenge even under the best of conditions, but it’s especially frustrating for someone with special circumstances, as illustrated in the engaging new character study, “Eternal Beauty.”

Life can be difficult when we don’t know what to make of it. Just ask Jane (Sally Hawkins), a middle-aged Welsh woman who drifts through life trying to figure it out. That’s a challenge, given that she suffers from schizophrenia and doesn’t know what to grab onto – or even how to do so. As a consequence, she aimlessly ambles from situation to situation, some seemingly “normal,” some delightfully humorous and others dangerously dark. She’s unable to discern which set of circumstances is “right,” either for her personally or for what she believes constitutes the greater scheme of things. And, as she wanders through this uncertain and sometimes-surreal landscape, her frustration with not being able to determine how to handle herself or the direction of her life becomes painfully obvious.

Jane’s circumstances represent more than an inability to cope; that comes with the territory of a larger issue – not being able to fundamentally figure out how life works or what’s best for her. Because of that, she stumbles through her daily existence, looking for the right fit. One could call this an extreme exercise in trial and error, but, when nothing seems to work, onlookers view Jane’s routine with a mixture of sadness, pity, anger and disdain, depending on who’s doing the observing. Their reactions and recommendations often complicate matters, as they’re largely unable to offer helpful advice. They sometimes even make matters worse by spewing uninformed criticism based on a lack of understanding of the underlying issue that Jane is experiencing, making her circumstances that much worse as she attempts to sort out that input in addition to everything else.

Jane (Sally Hawkins), a middle-aged schizophrenic patient, seeks to figure out how life works in the new character study, “Eternal Beauty,” now available for first-run online streaming. Photo courtesy of Samuel Goldwyn Films.

Jane’s existence is characterized by incidents and phenomena whose verifiability is sometimes dubious at best. She’s frequently beset by what appear to be hallucinations. She often makes statements and expresses opinions rooted in what seems to be questionable information. And she routinely receives phone calls from a mystery man (Robert Aramayo) who comes across as a possible past lover seeking reconciliation. It’s indeed difficult to verify how much of this is “real,” be it for everyone or just for her. The doubt cast by such unsubstantiated manifestations certainly raises issues for Jane, as well as those who care about her well-being.

Those standing by and watching Jane as she attempts to live her life can’t help but wonder how she ended up in such a state. Some, like her sister, Alice (Alice Lowe), and her doting father, Dennis (Robert Pugh), desperately want to understand and help her sort matters out. Others, such as her mother, Vivian (Penelope Wilton), her brother-in-law, Tony (Paul Hilton), and her other sister, Nicola (Billie Piper), are surprisingly hostile, demonstrating little patience for her erratic, unpredictable behavior and her cryptic, sometimes-caustic statements. And others, such as her psychiatrist (Boyd Clack), perfunctorily follow established, standardized protocols, regardless of whether they’re effective or suitable for Jane’s needs. But all of those responses, to one degree or another, don’t get to the bottom of Jane’s circumstances – or answer the fundamental underlying question raised in this paragraph’s opening sentence.

Some clues are offered in flashbacks to Jane’s youth, when her younger self (Morfydd Clark) suffered a series of setbacks – most notably being left at the altar and a failed effort at competing in a beauty pageant. The emotional devastation she suffered was truly profound. But, the closer one looks, the more one also sees that the kinds of responses to her behavior that are routinely thrust upon her now were present in her past as well. The impatience and intolerance typical of Vivian and Nicola, for example, are apparent in both of their younger selves; the behavior of Jane’s mother and her sister’s younger self (Natalie O’Neill) at times was downright cruel and, on occasion, nearly as unpredictably volatile as that of their target, suggesting that this mental health condition may run in the family. At the same time, Jane was not without well-meaning allies, again her father and Alice’s younger self (Elysia Welch), but their attempts at helping her then were about on par as they are now.

A family with a schizophrenic daughter/sibling seeks to provide help with her condition but with varying degrees of success, as sisters Nicola (Billie Piper, left) and Alice (Alice Lowe, second from left) and parents Vivian (Penelope Wilton, second from right) and Dennis (Robert Pugh, right) discover for themselves in the new character study, “Eternal Beauty.” Photo courtesy of Samuel Goldwyn Films.

However, even though these conditions from the past may have contributed to the development of Jane’s circumstances as an adult, they don’t appear to tell the whole story, and that’s apparent through her present behavior and her ostensible inability to figure out how to sort everything out. As she seeks to determine what circumstances constitute “normal” for her, whether or not she can find love (as she attempts to do in a wildly unpredictable relationship with a fellow mental patient and would-be aging rock musician, Mike (David Thewlis)) and how to find a suitable semblance of happiness in her life, Jane ponders the possibilities, acting upon them with varying degrees of success. And, through it all, she continues to deal with the assistance and recommendations offered by others, regardless of whether they offer any meaningful help.

To her credit, Jane seems to possess a special wisdom that those unafflicted with mental health issues appear to lack. In part, it accounts for some of her irritatingly acerbic remarks (and clearly explains the defensive reactions that others sometimes have to her spot-on observations). But, if Jane herself would only come to realize that she has this gift, it might help her to turn things around in her life. It just might provide her with answers to the core questions she’s unable to address by attempting to employ more conventional means, the kind the rest of us ordinarily rely on but that are wholly inadequate for her. And that could set her on a path to the satisfaction and fulfillment that have eluded her all of her life.

The overarching question in this story is, “What constitutes ‘normal’?” Is there some kind of standard that applies to everyone? And, if so, why does Jane have so much trouble conforming to it? Why aren’t the suggestions and treatments offered by others doing any good? Wouldn’t that suggest, then, that the one-size-fits-all notion doesn’t work? Is it thus possible that a more variable, personally relative standard is more accurate, more realistic?

The younger self of middle-aged schizophrenic patient Jane (Morfydd Clark, center) competes in a beauty pageant, one of a number of incidents that contributed to the onset of her condition, in the new character study, “Eternal Beauty.” Photo courtesy of Samuel Goldwyn Films.

For decades now, the principle that has come front and center in the metaphysical/New Thought community is the notion that we each create our own reality. Whether this concept is couched in terms of conscious creation, the law of attraction or even a simple belief in the idea that “life is what you make of it,” the underlying mechanics behind it are the same – that we draw upon the power of our thoughts, beliefs and intents in shaping the existence we experience, regardless of the form that reality ultimately takes, for better or worse. Indeed, if it’s something that can be employed to manifest an existence considered “normal” or “mainstream,” then couldn’t the same be said to materialize an outcome that’s outside of those parameters, one that’s “different” or “alternative”? Logically it would seem so, and, if that’s the case, then Jane’s experience would appear to offer an example of that notion at work.

Of course, given that Jane seems to have difficulty relating to the people and circumstances around her, one might legitimately ask, “Why would anyone want to create such an existence?” The challenges involved in that might be seen as overly daunting. Onlookers may view it as sad or tragic. And the creator of such a reality may have to endure endless frustration due to an inability to relate to his or her own circumstances in comparison to everyone else. It could be seen as a case of trying to squeeze the proverbial square peg into a round hole. Yet here’s Jane doing just that, so the question once again becomes, “Why?”

The underlying reasons for why we create the existence we do is, of course, no one’s business but our own. In many cases like this, it often involves materializing the conditions necessary to experience certain life lessons, no matter how unconventional they may be. It’s all part of the growth and development of our greater selves, to learn things that can only be achieved by undergoing such alternative life paths. Admittedly, this may not be the most ideal course, but, if it gets us what we want and need, then it naturally follows we’d pursue these circumstances to achieve the desired results.

Middle-aged schizophrenic patient Jane (Sally Hawkins, right) tries her hand at romance with an aging would-be rock musician, Mike (David Thewlis, left), in director Craig Roberts’s second feature, “Eternal Beauty.” Photo courtesy of Samuel Goldwyn Films.

In line with that, such experiences make clear that alternative approaches to life like this are just as viable and valid as those considered more conventional. Strange as they may seem to some of us, they may be perceived as perfectly suitable to those living through them. In fact, those traversing these different paths may look upon what the rest of us experience as just as “inadequate.” Experiencers of the alternative may indeed find that their realities enable them to “get into their oils,” a Welsh expression used routinely in the film that roughly means “finding oneself in one’s element,” no matter what that may constitute. As Jane searches for her “oils,” she may discover that an alternative lifestyle that those around her might readily eschew proves highly suitable for her, even if she’s alone in her convictions.

In presenting this view, the film thus provides us with a new outlook – indeed, perhaps even a new understanding – of what someone like Jane is genuinely experiencing. It suggests that she’s not actually enduring a mental illness but that she’s attempting to navigate her way through an alternate approach to reality creation that differs markedly from those around her. Some might be quick to contend that the setbacks she underwent in her youth and, potentially, the impact of family genetics on her physical being may offer “proof” of her “disease.” And it’s entirely possible that these influences may have played a role in helping to shape what she’s going through. Yet they may have also manifested as part of the larger experience she’s now attempting to maneuver through, that they’ve served as “tools” to help bring about the ends she seeks. So, with that in mind, Jane’s experience may actually prove valuable in helping us to better appreciate what those in her condition are actually undergoing and why – and to help us find more effective ways to interact with them that don’t disparage or mischaracterize them, their circumstances or what they’re ultimately attempting to achieve for themselves. This could shed a whole new light on them, us and the nature of reality itself.

Based loosely on the fact-based experiences of a woman known as “Calamity Jane,” this intense character study depicts a protagonist struggling to cope with her existence in an engaging and honest manner but without ever passing judgment on her life and behavior. The film never pleas for pity nor seeks to ridicule, but it quietly encourages us to consider possibilities that may have never crossed our minds before, and it does so more by “showing” than “telling” in its efforts to shape our views and perspectives. Despite a meandering opening segment – one that’s designed to drive home the relentless frustration Jane experiences (but that nevertheless still goes on a little too long) – the picture otherwise capably presents a candid depiction of what we call mental illness, without ever resorting to clichés, excesses or false impressions. Hawkins turns in yet another superb performance as the troubled protagonist, with fine support from Thewlis, Wilton and Clark. Director Craig Roberts’s second feature, now available for online streaming, represents an ambitious effort with a profound underlying message, one with the potential to radically reshape our outlooks on existence, mental well-being and what we consider “normal.”

Understanding the nature of our existence is often a life-long challenge. We often like to think we have it figured out, only to have our assessments torpedoed. And that process can be made all the more frustrating by continually examining it through the lens of what’s supposedly “normal.” We routinely second-guess ourselves, believing we must somehow hold ourselves up to some kind of established (though ultimately arbitrary) standard, only to discover (over and over) that “normal” is a relative quality for each of us, based on our beliefs and what we use them to create in our lives. Maybe we’d all be a lot better off if we just skipped ahead to that notion in the first place, holding to it, no matter how much each of our respective views of what constitutes “normal” differ from one another. We might well find that doing so leaves us a lot happier in the end. And isn’t that what “normal” is ultimately all about?

Copyright © 2020, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

Leave A Comment