‘The Neutral Ground’ exposes an obscured truth

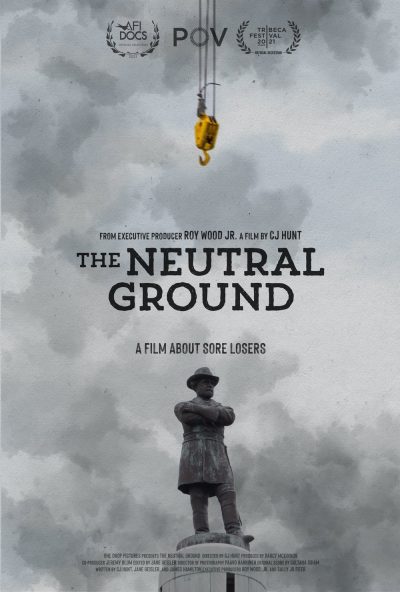

“The Neutral Ground” (2021). Cast: CJ Hunt (narrator and interviewer), Mitch Landrieu, Jason Williams, Christy Coleman, Michael “Quess” Moore, Malcolm Suber, Angela Kinlaw, Thomas Taylor, Karen Cox, Ashley Rogers, Dr. Ibrahima Seck, Abdul Aziz, Luther Gray, Freddi Evans, Dread Scott, Mr. Hunt, Darcy McKinnon. Archive Footage: Pierre McGraw, Donald Trump, David Duke. Director: CJ Hunt. Web site. Trailer. Movie.

When the truth remains hidden, it’s difficult to move forward and make progress in resolving thorny social issues. But, when it’s intentionally buried under a barrage of myths and lies designed to purposely obscure it, that makes the effort considerably more daunting. That doesn’t mean it’s impossible, though, as chronicled in the satirical and emotionally charged new documentary, “The Neutral Ground.”

In 2015, the New Orleans City Council considered a proposal to take down four statues honoring Confederate Civil War “heroes” and organizations, including those dedicated to General Robert E. Lee, commander of Southern forces, General P.G.T. Beauregard, the military officer who fired the first shots of the Civil War at South Carolina’s Ft. Sumter, and Confederate President Jefferson Davis. A hotly debated public hearing was held, characterized by passionate arguments from proponents on both sides of the issue. It was all that Council President Jason Williams could do to keep the hearing from getting out of hand. But, when the measure came up for a vote, it passed resoundingly, with only one Council member dissenting.

Mayor Mitch Landrieu, an ardent supporter of the proposal, was thrilled with the outcome of the vote. He hoped that the removal of the monuments would help to heal some longstanding pain, referring to the decision as one aimed at remembrance of, not reverence for, what the statues represented. And he hoped that the entire process would be wrapped up within a few months. If only it were that easy.

In the months that ensued, the removal plan remained a contentious issue, despite its official approval. Opponents filed lawsuits, and progress to take down the statues stalled. For all practical purposes, nothing was changing other than the growing volume of the public discourse.

Enter biracial comedian and social observer CJ Hunt. He had been a New Orleans resident for a number of years and was fascinated by what was unfolding before him. The field producer for Comedy Central’s The Daily Show was so intrigued that he even began work on a YouTube project about the subject. However, as the issue grew in intensity, he could see that an online video wouldn’t be sufficient for covering the depth and complexity of what was transpiring. And that is how this film project was born.

Hunt had a lot of questions, some of which were philosophical in nature and others of which were highly personal. As someone with a Black and Filipino background who grew up attending a predominantly White prep school, he tended to downplay his mixed-race minority heritage in order to fit in. But, as he entered adulthood, he had many unanswered questions about his background, especially when it came to why an apparent love of the Confederacy persisted among White Southerners and how he and the minority community should feel and react to that devotion.

To get to the root of this matter, Hunt had to do a deep dive into the history of the Confederacy to discover the hold it had on so many Americans through the years, including today. It was a process that took him to many locales throughout the South to unravel a variety of highly cherished myths, long-entrenched beliefs that helped explain the Confederate mystique, the reasons behind the erection of the monuments in the first place, and the perpetuation of the lore that has lasted through the years and continually fueled a culture built on dogma, lies and gross misperceptions. And, once these truths were exposed, Hunt was able to see where the outrage toward these symbols came from, an understanding that he sought to elucidate through this film.

Despite the reluctance of many Southerners to admit that the Confederacy lost the war, the fact remains that they were defeated, pure and simple. But, when up against such a harsh truth, there’s a natural tendency for those on the losing side to save face. As Hunt observes, this was particularly true when it came to healing the grief of the survivors of Southern soldiers killed in battle. Although there may have been a certain nobility in aiding grieving widows and mothers, those who orchestrated such efforts took matters a step further by concocting an entire mythology about the disappearance of an Old South that never existed. This led to a sentimental story about the South’s tragic defeat in the war known as “The Lost Cause,” a fable glorifying its fallen dead and sugarcoating a way of life that they unsuccessfully fought to defend.

As the myth grew, so, too, did the misconceptions about the reasons for the conflict. For example, one of the biggest fallacies was that the war was not about slavery, but, rather, about “states’ rights.” Of course, as Hunt found in his research of the secessionist documents that led to the creation of the Confederacy, the states’ rights in question were those associated with the “right” to own slaves, a contention boldly proclaimed in these historical writings. To compound matters, the attempted rewriting of the history of the South also included frequent statements about “the fair and kind treatment” that slaves received from their masters, with bad apples being more the exception than the rule.

Really? African-Americans would certainly tell a far different story. Which is why memorials exalting such a bald-faced deception have drawn the ire of those whose ancestors were subjected to an atrocious social system, not the genteel way of life so often depicted in books and films.

The film goes on to show how the mythology grew over the years after the war. As former slaves began to gain power during Reconstruction, African-Americans saw their level of empowerment rise, something that did not sit well with many White Southerners. First they lost the war, and now they were seeing their former “property” beginning to occupy positions of prominence. In their view, that was intolerable, prompting them to turn up the rhetoric of “The Lost Cause.” Increasingly massive memorials were being erected, and they were often placed in the proximity of locations like courthouses and government buildings. Such strategic placement was designed to send a message to let minorities know who was in charge. Even as late as 50 years after the war ended, this practice continued, a time long after many veterans and survivors of the conflict had died off. And, for those born in the interim, this was a way to indoctrinate them into a way of thinking that clung to outdated values and helped ensure the perpetuation of a power structure whose time had come and gone.

Hunt makes it clear that Southerners weren’t the only ones complicit in this movement. A number of Northerners played a role, too. For instance, many of the bronze statues destined for Southern locales were, in fact, cast in the North. Many of the books written about the Old South came out of publishing houses located in New York. Even the post-war reunified federal government played a role by backing away from Reconstruction when it became apparent it wasn’t working, removing troops and mothballing progressive programs, all in the interest of quelling Southern discontent and encouraging the notion that the US was once again one big happy family.

The bottom line in this, Hunt contends, is that the nation has been lulled to sleep about the truth of what really happened. Consequently, the issues associated with these buried truths have been ignored and allowed to fester. The discussion that we have long needed to have about this subject has been purposely set aside in hopes that it will simply go away, and the impact of this has been felt not only on a social scale, but also on an individual one. It’s been part of the reason, for example, why many young African-Americans have been left in the dark and/or have so many questions about their heritage, not unlike the director himself. It also accounts for why so many White Americans are unaware of where the anger of minorities comes from – and why it matters to make changes to rectify an intentionally obscured past.

So where do we go from here? As noted in the film, it’s unrealistic to expect that we can kill the myth simply by getting rid of its symbols. Indeed, even being able to make that happen can be a more protracted exercise than anyone realizes. It took New Orleans several years to eventually bring down the statues due to impediments like long legal battles and even Mayor Landrieu’s inability to find cranes to facilitate the process (their owners having been threatened if they aided the removal).

But that doesn’t mean we can’t take steps to get the ball rolling. Making the public aware of what really happened and telling the stories that have gone untold are good starting points. Considering how long these issues have persisted, they may not be resolved overnight, but we have to start somewhere, and films like this provide us with good places to begin. And Hunt has given us an excellent springboard to launch this process.

As director Hunt’s poignant visual essay so effectively shows, beliefs – no matter what they may be – are remarkably powerful and persistent phenomena. Thanks to the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains our thoughts, beliefs and intents manifest the reality we experience, these resources have the ability to materialize whatever they represent, for better or worse. And, in the case of the circumstances depicted in this film, they have done so with tremendous staying power, commemorating individuals and events from over 150 years ago. This brings true meaning to the notion of beliefs being capable of memorialization as tangible materializations, powerful, physical symbols of ideas, no matter how heinous or unacceptable they may be – or have become.

This principle can obviously be applied for positive, uplifting ideals as well. But, in the case of the Confederate statues in New Orleans and other municipalities of the American South, they have been erected – and maintained – to promote and perpetuate an agenda backed by beliefs that are antiquated and out of touch with contemporary thinking. That support, which has been sustained by the same beliefs that prompted their original placement and dedication, is what filmmaker Hunt and groups promoting the monuments’ removal have been seeking to expose, making the real intents behind them known in order to change the narrative and set the record straight.

Changing entrenched beliefs is often difficult, again due to the power and persistence underlying them. But it’s not impossible by any means. It requires the formation and promotion of new beliefs, notions that clear away the obscuring camouflage and reveal the truths that have been hidden in the shadows of these falsely glorified icons for all these many years. And, when those revelations surface, they have the power to change hearts and minds – and to win over the support of those who have been uninformed or who have willfully chosen to stay asleep and in denial. Those new beliefs thus have the power to write a new public narrative, one that wipes clean the longstanding falsehoods and is capable of launching a new dialogue, one in which an obscured truth at last becomes known.

The chances of achieving such a result are enhanced when we tackle the project as a collaborative effort, an act of co-creation. By taking this approach, we have an opportunity to tap into the power, energy and beliefs of multiple sources. In addition to the efforts of individuals like the director and crew of this film, the initiative garnered further support from organizations like Take ’Em Down Nola, the New Orleans Slave Trade Marker Project and the staff of the Whitney Plantation Museum, all of which are featured in the picture. This goal also benefitted from efforts in other cities with Confederate statutes where similar initiatives were launched, such as Charlottesville, VA, Baltimore, MD, Durham, NC, Richmond, VA and Charleston, SC. By making this more than just a New Orleans issue, proponents of this endeavor have created a groundswell of support to change the nation’s landscape – not just physically, but also in the minds and consciousness of its citizens.

This is not to suggest that the memorials are entirely without merit. However, what needs to change is an understanding of the meaning for why they were erected and what we should take away from their original creation. Instead of glorifying the remorseful failure of a defeated secessionist nation, they should serve as powerful reminders of the morals and values that said nation stood for – intolerance, involuntary servitude, racial hatred, and other unspeakable social and ethical atrocities. Putting the statues into that context, perhaps by placing them in designated locales dedicated to fostering that purpose, would be a means for reminding us of the errors of our ways rather than the exaltation of man’s bigotry and foolhardiness. That, of course, would imbue these idols with an entirely new meaning, backed by a new set of beliefs, notions different from those for which they were originally established. These new ideas can transform the dialogue, sending a powerful message both to those who once lauded the existence of these landmarks and, one would hope, an enlightened posterity.

This campaign this represents a tremendous learning opportunity, one aimed at providing us all with a tremendous life lesson. As is often widely acknowledged, those who don’t learn from the past are indeed destined to repeat it. As Hunt stresses in this film, this is a chance for America to take off the blinders, to learn what really happened and to discover how we tried to bury the truth for the sake of other considerations. It’s an opportunity to learn the dangers of denial, of how we placed the expediency of fulfilling certain goals over openly acknowledging some painful realities, a course of action for which all of us – Northerners and Southerners alike – share the guilt that has persisted to this day. And it’s a situation that can only be rectified by changing the beliefs that write the narrative in which we all play a part, both individually and collectively.

Aptly subtitled “A Film About Sore Losers,” this superb debut documentary feature by director Hunt draws upon a modern-day Battle of New Orleans – one aimed at removing public symbols commemorating a failed social system that celebrated slavery, racism and White supremacy. In exposing the false narrative that has kept this myth alive for over a century, the filmmaker tells a story that’s both stunningly comic and utterly tragic. Hunt’s skillful tongue-in-cheek questioning and editing techniques effectively blow the lid off the ignorance, cynicism and hypocrisy of the alleged virtues that sanction fellow humans being treated as property and inherently inferior. As the premiere episode of the new season of the PBS documentary series POV, this excellent offering is now available for streaming online from the program’s web site. Hunt’s film succeeds both as a work of filmmaking and as an enlightening and educational vehicle, one that every American should see if we ever hope to resolve these long-simmering conflicts.

Copyright © 2021, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.