‘Cured’ chronicles a remarkable breakthrough

“Cured” (2020 production, 2021 release). Cast: Interviews: Dr. Frank Kameny, Kay Lahusen, Dr. Charles Silverstein, Rev. Magora Kennedy, Dr. Lawrence Hartmann, Ron Gold, Dr. Richard Green, Dr. Richard Pillard, Don Kilhefner, Richard Socarides, Dr. Saul Levin, Harry Adamson, Dr. Robert Campbell, Gary Alinder. Archive Footage: Barbara Gittings, Dr. John Fryer, Dr. Charles Socarides, Dr. Robert Spitzer, Dr. Judd Marmor, Rick Stokes, Dr. Alfred Kinsey, Dr. Evelyn Hooker, Dr. Irving Bieber, Dr. Alfred Bloch, Dr. Lawrence Hatterer, Dr. Jerry Lewis Jr., Sally Duplaix, Morley Safer, Mike Wallace, David Susskind, Harry Reasoner, Roger Mudd, President Bill Clinton, President Barack Obama. Directors: Patrick Sammon and Bennett Singer. Web site. Trailer. PBS Broadcast Site.

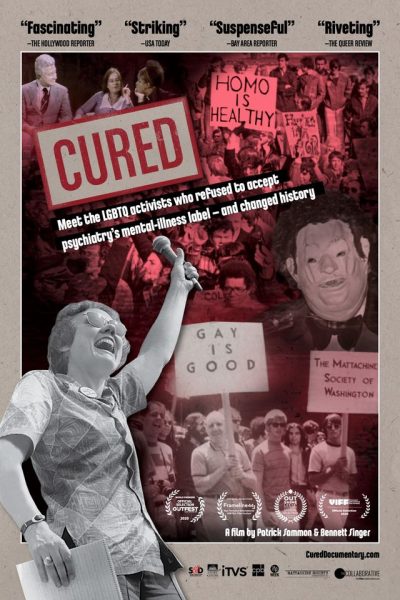

Imagine being saddled with a label that was anything but true. What’s more, imagine being cruelly persecuted for that erroneous characterization, subjected to emotional and even physical abuse and mutilation, making life unbearable. Prejudice, discrimination and harassment are nearly constant companions, and such treatment is often inflicted by one’s nearest and dearest, including family members. If it’s possible to picture that, then you have an idea what it might have been like for members of a patently and unfairly disrespected minority community that did nothing to earn or deserve such disgrace. But breakthroughs to such treatment are possible, a story chronicled in the captivating new documentary, “Cured.”

How do you cure millions of supposedly mentally ill people overnight? By publicly proclaiming that their “affliction” of homosexuality isn’t an affliction at all. So it was in 1973, when the American Psychiatric Association dropped this “condition” from its official list of mental maladies. It was a hard-fought victory in the LGBTQ+ rights movement, one that’s meticulously detailed in this superb new documentary from directors Patrick Sammon and Bennett Singer.

Given the widespread and increasing acceptance of the gay community these days, one might legitimately wonder how and why any kind of effort was needed to recognize it as anything other than normal. Yet times were quite different in the past, and acceptance didn’t come easily. In fact, at one point, there was pervasive hatred of gays, their manners, preferences and lifestyles scorned and considered on par with the vilest of criminals – an apropos analogy given that homosexual acts were generally treated as crimes in themselves.

More than that, however, homosexuality was considered a mental illness. It was first classified as a “diagnosable” disorder in the 1952 edition of the APA’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, and psychiatrists embraced the designation with general consensus. However, opponents of this idea saw this as pseudoscience based on incomplete and distorted data in that it only took into account the experiences of troubled gay individuals, not the community as a whole. Some argued that, if this analogy were applied to heterosexuals, then any straight individuals who saw therapists could also be labeled mentally ill by virtue of their heterosexuality. Nevertheless, despite such protests, this flawed analysis was regarded as the norm and applicable to all gay individuals.

Why was this idea so widely and readily accepted? The 1950s were a conservative time in America, and the traditional nuclear family was unquestioningly the accepted standard. The contention that gays were anomalous and out of step with this idealized notion was thus institutionalized by the psychiatric community, especially with the support of outspoken, high-profile practitioners like Drs. Charles Socarides, Irving Bieber, Lawrence Hatterer, Alfred Bloch and Judd Marmor (who, ironically, would later reverse his view).

Homosexuality was believed to be a learned (but sinful and criminal) behavior, one actively discouraged through scare tactics often thrust upon impressionable school age children. Yet it was also believed that the “condition” could be reversed. Treatment at mental institutions was the cure, but it was more often coerced than recommended. Gays were relentlessly treated like second class citizens, and their exposure led to shame, firing from jobs, the curtailment of career opportunities, housing discrimination, blackmail, loss of child custody and other indignities. The only viable alternatives at the time were cover marriages and staying closeted.

Those who underwent “treatment” at mental institutions suffered horrendously. Among the “cures” commonly used were electroshock therapy, lobotomies and castration. Then there was the widespread practice of aversion therapy, which consisted of electrical shocks being given to patients’ genitals when those individuals were shown erotic photos of members of the same sex. The thinking was that they could be “conditioned,” not unlike Pavlov’s dog, to respond to the expectation of being averse to same-sex attractions and favorable toward opposite-sex attractions.

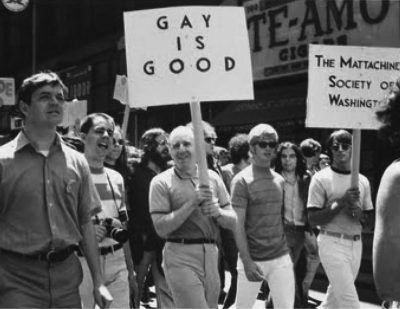

In the early days of the gay rights movement, members of some of the first organizations fighting for this cause, such as the Mattachine Society and the Daughters of Bilitis, believed that they needed to eliminate the mental health stigma if the community were to make any progress. Removing the sickness label had to come first. And, ironically enough, some of the biggest boosts in that regard came from the research of professionals (and unexpected allies) like Dr. Alfred Kinsey, Dr. Evelyn Hooker and even Sigmund Freud, all of whom contended that homosexuality was no more of a mental disorder than heterosexuality was.

But these initiatives were just the beginning. Given the many protest movements that emerged in the 1960s, such as those involving civil rights, women’s rights and opposition to the Vietnam War, the gay rights movement was a natural outgrowth of that culture of rebelliousness. And then came the 1969 Stonewall uprising, a protest at a popular New York gay bar that was routinely raided by authorities until one night when the community stood up to the police and said “Enough!” This event changed the course of the movement and brought it above board on a wide scale.

With greater backing, gay activists turned their attention to making a concerted effort at forcing the APA to eliminate the mental illness designation. In 1970, at the group’s annual convention in San Francisco, activists infiltrated the event and began speaking up, contending “there is no cure for that which is not a disease.” Gays told psychiatrists what it’s like to be gay, no longer willing to sit back and be told by them what it means to be gay. The aim was to challenge the APA’s patriarchal, judgmental attitude, an initiative that prompted many members to run for cover. However, there were others – mostly younger and more open-minded psychiatrists – who were willing to listen. Out of this, support arose among more enlightened practitioners, like Dr. Richard Green, who wrote a groundbreaking paper on the subject, suggesting that the science used to justify the APA’s position just didn’t hold up. These psychiatrists, many of them heterosexuals, thus sought to reform the APA from within.

At the same time, gay references were also increasingly creeping into popular culture, such as TV sitcoms, such as All in the Family and The Mary Tyler Moore Show, as well as TV talk shows and movies like “The Boys in the Band” (1970). Gays themselves also became more outspoken in public venues, as seen in an appearance by activist Rev. Magora Kennedy on The David Susskind Show, an experience through which she proclaimed “I’m not going to let you dictate to me about who I am.” Simultaneously, however, the psychiatric profession’s Old Guard dug in, led by dogmatic practitioners like Dr. Charles Socarides, who sought the establishment of a national treatment center for this “disorder” (an ironic proposition given that his own son, Richard, was an emerging gay man at the time).

At the 1972 APA convention in Dallas, a panel discussion platform was set up to debate the sickness label featuring activists Barbara Gittings and Dr. Frank Kameny, as well as “Dr. H. Anonymous,” a self-proclaimed gay psychiatrist (Dr. John Fryer in disguise), whose heartfelt presentation struck a nerve, speaking to the loss of “our honest humanity.” At another gathering, gay therapist Dr. Charles Silverstein made a presentation in which he told psychiatrists that they had to choose between the undocumented theories that had caused considerable harm to many people or the scientific studies to the contrary. These events, in turn, led to the 1973 APA convention in Honolulu, at which gay rights activist Ron Gold gave a stirring presentation titled “Don’t make me sick!”

The turning tide led to the passage of a resolution by the Northeast District Branch of the APA seeking to end gay discrimination and to eliminate the gay sickness diagnosis, an initiative whose impact gradually filtered upward throughout the profession. This momentum strengthened with a 60 Minutes story featuring Silverstein and his efforts to practice therapy aimed at “freeing” gay individuals from their traps of self-imposed isolation, a stance that they had unwittingly come to embrace based on their prior experiences with traditional shame-based therapy.

On December 15, 1973, the APA leadership announced its decision to eliminate the gay sickness diagnosis. According to Dr. Richard Green, millions of individuals were cured overnight with the stroke of a pen. Drs. Socarides and Bieber fought the decision, contending that most psychiatrists didn’t buy into the idea, but their 1974 referendum on the move failed. The mental illness label was at last gone. And, where the LGBTQ+ community was concerned, this was just the beginning.

The gay community’s success in convincing the APA to drop the mental illness stigma was a tremendous accomplishment, and “Cured” does an excellent job in telling that story clearly, concisely and effectively in its economical 80-minute runtime. It profiles the major players and events in this initiative, and it shows how significant, meaningful progress can indeed be made swiftly once a critical tipping point is reached. But, perhaps most importantly, the film chronicles the efforts of courageous, determined individuals – both gay and straight – to make this happen, paying particular attention to the qualities they possessed to bring it about. That’s important, because these attributes figured largely in the beliefs and convictions they held, the building blocks of the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains we draw upon these resources in manifesting the reality we experience. And, even if these pioneer activists were unfamiliar with the philosophy, they certainly were masters of its principles, wielding them with the skill and dexterity of expert swordsmen.

For starters, the activists and enlightened psychiatric professionals who worked toward change were firmly rooted in the belief that it was attainable. They saw the flimsy evidence that was being peddled to prop up an erroneous and inexcusable practice and knew that, if it were exposed widely enough, their arguments could be used to change the hearts and minds (and, subsequently, the policies and practices) of those who were allowed to let their misguided viewpoints hold sway virtually unchecked. They believed they could invoke change to correct this longstanding atrocity, thus validating a commonly held conscious creation principle that “the only point in suffering is learning how to stop.”

To make this possible, the activists and advocates needed to become galvanized in particular sets of beliefs. First, they needed to convince themselves that the existing limitations that had been holding the gay community back could indeed be overcome. Next, they needed to imbue themselves with faith in themselves and their convictions that change could be implemented, even if the means for doing so weren’t readily apparent, thereby proving that necessity truly is the mother of invention. But, above all, they needed to conquer their fears and live heroically in carrying forth with their plans – not an especially easy course at a time when the prevailing conditions were much less tolerant and those undertaking these ventures could stand to lose a lot.

As history has shown, though, this hard-fought victory opened the flood gates for the gay rights movement, launching a series of subsequent reforms that have carried through to this very day. Still, however, as exemplified by Dr. Socarides’s efforts to overturn the APA’s December 1973 decision, there is yet a need to remain vigilant. As noted in this film and others, like the fictional feature “Boy Erased” (2018) and the recently released documentary “Pray Away” (2021), the threat posed by dangerous, unproven treatment programs like conversion therapy remains and must be continually opposed to prevent backsliding into the days of the gay dark ages of years past. Even though the LGBTQ+ community may be generally convinced that no further “cures” are needed, the possibility that those with misguided agendas might nevertheless try to implement or impose them must be opposed with the same dedication, diligence and commitment that rendered the APA policy outmoded in the first place.

Without a doubt, “Cured” is one of the best documentary releases to have come along in quite some time. The film features a wealth of insightful interviews with those who were on the front lines, as well as ample archive footage depicting key moments in the effort to bring about this decisive change. The film is thus a fitting tribute to many unsung heroes in the gay rights movement, giving them the accolades they have long deserved. Sammon and Singer’s fine offering is great viewing for those who believe in social justice, and it’s especially highly recommended for younger viewers in the LGBTQ+ community who may not – but need to – know the history of their peers and their courageous efforts in bringing about the rights they now so freely enjoy.

“Cured” has principally played the film festival circuit over the past year and has been featured in various special screenings. However, its big breakout opportunity is about to arrive on October 11 – National Coming Out Day – when the film with be broadcast as part of the PBS documentary series Independent Lens. In the run-up to that event, the film will also be featured in the September 9 edition of The Good Media Network’s Mission Unstoppable video podcast on Facebook Live in which host Frankie Picasso and yours truly will interview directors Patrick Sammon and Bennett Singer about this excellent documentary.

It never ceases to amaze me how often humanity goes looking for problems where none, in fact, exist. Fool’s journeys such as these often cause more harm than good and lead to the establishment of misconceptions that become accepted and embedded in the culture, making their reversal and elimination exceedingly difficult, requiring Herculean efforts to effect change. Considering how many times this has happened throughout history, one would think we would have learned this lesson by now, yet such prejudicial fallacies persist in various contexts, often necessitating efforts like those depicted in this film to see them rectified. If the moral of this story helps to further the cause of learning that lesson, then we can only hope that the sacrifices made by those who endured this ordeal were not in vain. At the same time, though, we must ask ourselves, how many times must we experience scenarios like this to finally get things right? If we adjust our outlooks and beliefs so that we don’t pursue trouble needlessly, we’ll be much better off in the long run – and discover that there’s no need to have to go in search of cures in the first place.

Copyright © 2020-2021, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.