‘The Ice King’ fuses vision and perseverance

“The Ice King” (2018). Cast: Interviews: Johnny Weir, Robin Cousins, Dorothy Hamill, Dick Button, Heinz Wirz, Rita Curry, Christa Fassi, Cathy Foulkes, Meg Streeter Lauck, Nancy Streeter, William Whitener, Elva Corrie, Nathan Birch, David Spungen, Freddie Fox (narrator). Archive Footage: John Curry, Carlo Fassi, Vladimir Kovalyov, Donald Jackson, JoJo Starbuck, Peter Martins, Twyla Tharp, Ed Mosler, Joseph Curry. Director: James Erskine. Screenplay: James Erskine. Web site. Trailer.

When faced with a seemingly insurmountable challenge, it would be easy to throw in the towel. At the same time, though, when we also know that what we wish to bring into being is something we must do, such awareness compels us to strive ever forward, regardless of the effort and cost involved. But how can that be accomplished? It helps to have a vision and the persistence necessary to flesh it out, qualities depicted in the inspiring sports documentary, “The Ice King.”

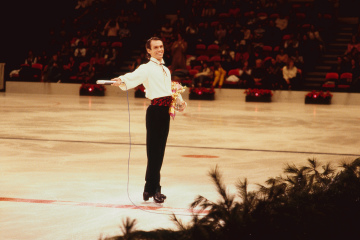

John Curry may not be a household name, but his impact was certainly considerable. After winning the British and European figure skating championships, he went on to make a name for himself as the gold medal winner at the 1976 Winter Olympics in Innsbruck, Austria, followed by the sport’s world championship, his four titles solidifying his status as a grand slam champ of the sport. As impressive as this accomplishment was, however, Curry’s greatest achievements were yet to come.

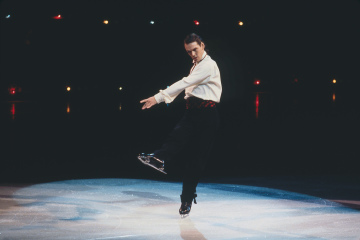

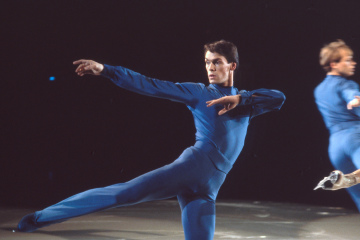

In a sport that was strongly characterized by pronounced athleticism at the time, Curry sought to turn it on its ear by making it more artistically expressive. He envisioned supplementing the sport’s high-flying jumps with graceful, fluid movements featuring dramatic, emotive gestures, an attempt aimed at adding distinctive flowing lines to the routines. While those qualities were considered acceptable for women, it was not looked upon as favorably in the men’s competitions, largely because, in the less tolerant ways of the time, such artistry was frowned upon as less than masculine and conveyed the “wrong” impression about the sport’s participants. Curry, however, who had aspired to be a dancer in his youth – an ambition looked down upon by his strict, close-minded father, Joseph – was determined to introduce it in hopes that it would help to reshape the sport and take it to a new level.

Curry worked hard for years to bring this about. Under the guidance of coaches Carlo and Christa Fassi, he honed his skills and incorporated these elements into his routines. And, by 1976, when he was ready to pursue Olympic gold, he had perfected his craft, permanently changing the nature of men’s competitive figure skating.

But Curry saw the Olympic title as a springboard to greater things. In preparing to turn professional, he was not content to follow the path taken by many of his figure skating peers, most of whom signed on with touring ice shows in which they were cast as performers of kitschy, cartoonish routines. As Curry put it, after years of serious artistic training, he could not envision himself putting on an ice skating routine dressed up in a Bugs Bunny costume. He wanted his professional career to reflect the sentiments that he had been longing to bring to the sport.

Curry thus established his own skating troupe, one in which he worked on developing routines that incorporated classic dance movements choreographed by such notables as Peter Martins and Twyla Tharp. His programs featured flamboyant costuming and diverse music from a variety of genres, including tangos, modern electronic compositions, and classical pieces from the likes of Claude Debussy and Erik Satie. In this way, he sought to bring the artistry to professional figure skating that fulfilled his dreams and was noticeably absent from the popular touring ice shows. This attempt at elevating the nature of the art drew widespread attention from skating peers, many of whom flocked to the opportunity to join a troupe such as this. Curry was joined by such noteworthy skating professionals as Dorothy Hamill, 1976 Olympic gold medalist and world champ, and JoJo Starbuck, bronze medalist at the 1971 and 1972 world championships.

The new look that Curry gave to figure skating drew raves, not only from fans of the sport, but also from the arts community, who relished the fresh, innovative approach he was infusing into both the skating and dance worlds. However, despite the critical acclaim his company’s performances received, the troupe experienced ongoing issues with logistics and finances. Over time, it became increasingly difficult to stage the kinds of productions that Curry wanted to create. And these issues added to long-simmering problems that the skating star had been wrestling with.

During much of his upbringing and young adulthood, Curry suffered from depression. Much of that involved his homosexuality, a secret he generally kept closely guarded. Nevertheless, it was an underlying source of stress in a number of his relationships, such as that with his father, who suspected his son’s orientation and did whatever he could to dissuade anything that might “encourage” it, such as his interest in dance. In fact, as Curry put it, his father was agreeable to his son’s participation in skating because “at least that was a sport,” unlike dancing, which carried other stereotypical connotations. And, then, to make matters worse, the elder Curry compounded circumstances by committing suicide.

As Curry tentatively began exploring his sexual leanings, he began a relationship with athlete Heinz Wirz. Even though the romantic involvement didn’t last, Curry and Wirz remained lifelong friends and corresponded frequently. Excerpts of their letters are included as voiceovers in the film, the contents of which include telling revelations about Curry’s feelings related to his struggles with managing his sexuality and mental health, both during his days of competition and as a professional.

These issues impacted Curry’s skating endeavors, especially those related to his sexuality. In an interview before his Olympic victory, he spoke candidly about it with a reporter, who publicly outed the skater 24 hours after his win. Curry confirmed the eyebrow-raising reports shortly thereafter, a courageous move at the time. It nevertheless made him the first openly gay Olympian to come out.

Curry subsequently embraced his sexuality, but, unfortunately, he fell victim to the emerging AIDS crisis. Over the next few years, due to the financial difficulties of his troupe and his failing health, his performances trailed off and eventually stopped. As his illness progressed, he retreated into seclusion, passing on in 1994 at the age of 44.

Even though Curry’s career may have been cut short, he left a lasting legacy that changed the sport for years to come. His influence permeated skating, impacting the routines of competitors like Britain’s Robin Cousins, 1980 Olympic and world champion, and American Johnny Weir, three-time US champion and 2008 world’s bronze medalist, both of whom are interviewed in the film about how Curry inspired them. It’s rare when one individual can have such profound impact on changing the course of an art form, but Curry did that, and skating fans can thank him for that.

John Curry faced a number of challenges in his life, both personally and professionally, yet he managed to address many of them successfully. While these ordeals were indeed daunting, Curry summoned up the gumption to take them on. And that occurred primarily because he believed he could overcome them, despite the difficulties, especially where his own insecurities were concerned. That’s important to recognize, because our beliefs dictate how close we come to fulfilling our aspirations, the cornerstone principle of the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains we draw upon these intangible resources in manifesting the reality we experience. Even though it’s unclear whether Curry ever heard of this doctrine, it’s apparent through his accomplishments that he was a master of its principles.

Two qualities helped to set Curry apart. First and foremost, he was a visionary when it came to skating. He envisioned what he was trying to achieve – fusing sport and art – and then went out and did it at a time when prevailing conditions were less than conducive for doing so. Athletic and social prejudices governed what was considered acceptable, but Curry’s groundbreaking approach defied those conventions. He was taking a big chance, considering that it was unclear whether the “rebellious” nature of his routines would be embraced in a milieu where tradition persisted and change didn’t come easily.

Nevertheless, Curry came out on top in these endeavors, largely because of a second quality – perseverance. Even at those times when he may have wanted to give up – a course that could have easily been facilitated with his mental health issues – he managed to hang in and find the means to follow his dreams. When he struggled financially during his pre-Olympic training, for example, her found a willing sponsor, sports enthusiast Ed Mosler, to bankroll his efforts, including the hiring of the much-in-demand Fassis as his coaches. This enabled him to keep going at a time when it might have been just as easy to walk away.

This combination of vision and perseverance thus made it possible for Curry to live up to his own expectations. And those qualities fell into place thanks to beliefs that made their presence in his own mindset possible. Not only did they help him succeed as a competitive and professional skater, but they also empowered him to grow comfortable in his own skin personally. Allowing oneself to be openly gay at a time when many members of the LGBTQ+ community were still hidden in the recesses of their personal closets, Curry didn’t back off once his secret was revealed. He may not have been comfortable with the way this revelation came about, but he would not allow personal demons, the ghosts of his upbringing or the close-minded thinking of others to continue to hold him back. He had grown comfortable with his orientation and was not afraid to let the world know, an attitude that was surprisingly well accepted at the time and ran far afield from the experiences he underwent while growing up in the shadow of a less-than-tolerant father figure.

The impact of his visionary and persevering beliefs, in turn, made it possible for Curry to tackle another significant obstacle – overcoming his fears and limitations. If he were going to accomplish big things in his life, both professionally and personally, he could not allow these hindrances to block his path, no matter how challenging it may have been in addressing them. In his competitive skating life, for example, he could not let the attitudes of the judges scoring his routines intimidate him. He knew he would have to lay his cards on the table (or, in this case, in the ice) and let the work speak for itself, hoping that his evaluators would be able to see his routines for the bold, inventive statements that they were. Fortunately, they did, and that led to his accolades, which, in turn, enabled him to parlay his award-backed clout into the professional endeavors he went on to pursue. One achievement led to another and then to another that, ultimately and collectively, allowed Curry to persevere and eventually fulfill his vision.

Given that Curry was always progressing in his achievements, on some level, he also seemed to understand that nothing lasts forever, principles that were, again, equally applicable to his professional and personal undertakings. While Curry’s post-competition projects certainly were revolutionary in the world of professional skating, they presented their own sets of challenges that made their perpetuation difficult. Nevertheless, that did not deter him from carrying on, fulfilling one artistic and athletic accomplishment after another, even if they weren’t always replicated more than once.

While those accomplishments were bring fulfilled, however, they represented tremendous achievements, and Curry made the most of them, both individually and with the members of his skating troupe. He relished these attainments, immersing himself in those moments. And, in doing so, Curry embodied the principle that the point of power is in the present. Even if these moments weren’t meant to endure, they incorporated the qualities of grandeur and magnificence during the time while they existed, no matter how brief, producing memorable creations that lasted long after they were over with.

That’s a key concept in conscious creation – that our manifestations represent moments of perfection in their own right, living up to their potential and yielding things of intrinsic, even if fleeting, beauty. Their importance should be underscored, though, for they also enabled the ongoing process of personal evolution, something that was quite apparent in Curry’s routines. In this way, Curry’s efforts also reflected the concept that everything is in a constant state of becoming, one of the chief aims of this philosophy. And, in doing so, Curry made it look effortless and inherently beautiful.

One could say that Curry’s life itself embodied the foregoing principles. He virtually disappeared from the skating stage in his mid 30s, well before what many anticipated would be a much longer professional career. And, with his death at 44, Curry, as an individual, left us at a point that many considered too soon. But, while he was here, Curry made the most of the time he had and lived up to his potential to a degree greater than many of us will ever hope to achieve. His life may have been shorter than expected, but, while he was here, he truly was the Ice King.

Curry revolutionized a sport – and later an art form – that had long been driven by sheer athleticism rather than inspired artistry. But, for all his artistic and athletic achievements, Curry also had to conquer issues that sometimes held him back throughout his life. Director James Erskine’s superb 2018 documentary comprehensively covers all aspects of Curry’s complicated life and death, incorporating a wealth of rare archive footage and featuring insightful commentary from friends, colleagues, and fellow figure skaters Robin Cousins, Johnny Weir and Dorothy Hamill, as well as past interviews with Curry himself. The film is a fitting tribute to a remarkable talent who left a tremendous legacy as a competitor, as an artist, and, above all, as an individual.

The film is available for streaming online from multiple sources. In addition, with the upcoming 2022 Winter Olympics only a few months away, “The Ice King” has been showing up in special screenings in the run-up to the games. No matter how or where one sees it, though, it’s definitely worth the time.

Going for the gold is a metaphor we’re all familiar with, one that applies to more than just the Olympics. Curry applied that notion to all the ventures he undertook and found the means to make those goals possible. The example he set is one that we can all draw from in our own endeavors, regardless of the stage on which those adventures unfold. And, when armed with that kind of inspiration, there’s no telling what we might accomplish, achievements that might well enable us to skate away with medals all our own.

Copyright © 2021, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.