‘Nothing Compares’ looks at the perils of being ahead of one’s time

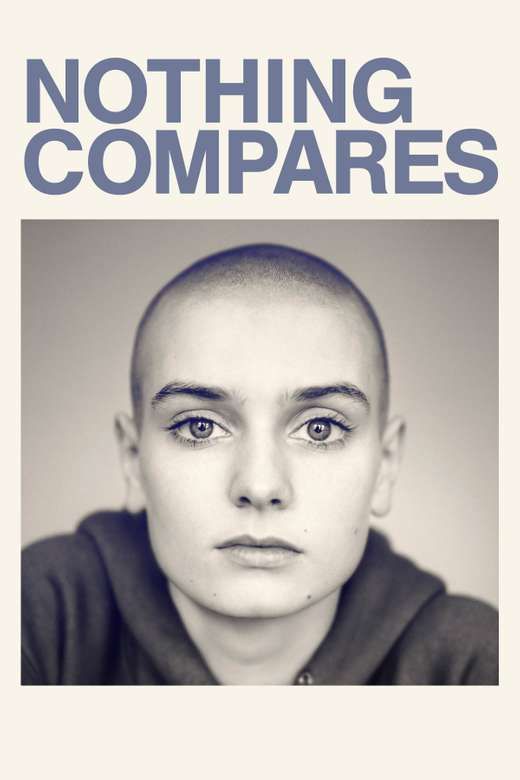

“Nothing Compares” (2022). Cast: Audio Interviews: Sinéad O’Connor, Kathleen Hanna, Chuck D, Peaches, John Reynolds, John Maybury, Elaine Schock, Róisín Ingle, Clodagh Latimer, Jeannette Byrne. Archive Footage: Kris Kristofferson, Charlie Rose, Joe Pesci, Phil Hartman, Jan Hooks, Tim Robbins, Bob Dylan, Bob Marley, Haile Selassie, Gay Byrne. Director: Kathryn Ferguson. Screenplay: Eleanor Emptage, Kathryn Ferguson and Michael Mallie. Web site. Trailer.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Sinéad O’Connor emerged seemingly out of nowhere as one of the biggest names in the music business. She became known for having one of the most distinctive sets of pipes in the industry, with an ability to jump octaves in a single bound and to be able to go from a soft whisper to a banshee scream at the drop of a hat. She also developed a uniquely characteristic ability for vocalizing that exhibits what I’ve often called “harmonious dissonance,” a form of singing where she could seamlessly blend both beautiful and edgy sounds to create a distinctive style all her own. And, as illustrated on her first three albums – The Lion and the Cobra (1987), I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got (1990) and Am I Not Your Girl? (1992) – O’Connor could more than capably handle material ranging from kickass rock numbers to sweet sincere ballads to Big Band standards and do justice to each of them. She even had one of the era’s biggest hits in “Nothing Compares 2 U,” a single off of her second album written by Prince that became better known and more popular than the version penned and performed by its composer. She was quite the talent indeed.

But, just as quickly as she rose to prominence, O’Connor vanished with equal rapidity, and this had nothing to do with her music; rather, it was due to her unabashed candor and a willingness to express views that many at the time found unpopular or unacceptable, if not offensive. For instance, O’Connor was an outspoken critic of the Roman Catholic Church (and its collaborators, the Irish government) in chastising these institutions for their longstanding treatment of at-risk women housed in asylums who were put to work in facilities known as “the Magdalene laundries,” where they were virtual slaves. She also openly criticized Ireland’s lack of support for women’s rights, abortion rights and LGBTQ+ rights. And these “radical” views did not set well with the public in this conservative, largely Catholic country.

However, O’Connor’s outspoken opinions in these areas were nothing compared to a pair of incidents that happened in the US. The first was her refusal to perform at a 1990 stadium concert in New Jersey where the facility played the national anthem before the start of each of its events. The US was involved in the first Gulf War at the time, so patriotic themes were running especially high throughout the country. But O’Connor said her opposition to the war was so strong that she could not perform if her concert was preceded by such a blatant symbol of that conflict. O’Connor’s stance drew harsh criticism from the American public, including singer Frank Sinatra, who openly threatened to “kick her in the ass,” according to media reports at the time. Radio boycotts and other retributive measures ensued, as the once-universally beloved performer’s reputation became heavily tarnished.

The second incident occurred on an episode of NBC’s Saturday Night Live, where O’Connor was scheduled to appear as the show’s musical guest. But, unbeknownst to the show’s producers, O’Connor made last-minute changes to her performance that outraged many in the national television audience. O’Connor performed an a cappella version of the Bob Marley song “War,” a composition based on a 1963 speech calling for world peace given by Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie at the United Nations General Assembly. However, in O’Connor’s version, she treated the song as a clarion call to fight the Roman Catholic Church for its cover-up of unprosecuted child abuse at the hands of priests, concluding the piece by tearing up a photo of Pope John Paul II, referring to the pontiff as the real enemy behind this atrocity.

O’Connor’s SNL appearance effectively sank her career. When she appeared at a tribute concert to Bob Dylan not long thereafter, she was met with a mixture of cheers but also highly vocal boos. She even faced death threats. Her music virtually disappeared from the airwaves as she disappeared from public view. As quickly as she became an icon, she subsequently became a pariah. And, even though she has continued touring and recording since then, most of her works are virtually unknown – and seldom heard. She effectively became invisible.

So how did such a radical shift in fortunes occur? To understand that, one needs to understand O’Connor, and that’s one of the goals that this film seeks to accomplish. This is where viewers need to take a step back and look at the person and her beliefs – and how they shaped how events played out.

To truly understand O’Connor’s beliefs and how she has made use of them, however, one must look to her upbringing, which was often fraught with challenges and difficulties, particularly with her abusive mother. As a teenager, she was sent to one of the aforementioned Magdalene asylums to “correct” her behavior for acts of shoplifting and truancy. But, despite the largely negative reputation of these institutions, her stay nevertheless provided her with an opportunity to help her develop her music, even though she struggled with the strict conformity required of residents. The stringent rules she was forced to deal with thus set in motion the formation of beliefs that would later come to be characterized by unrestrained expression. These conditions helped establish a strong sense of personal integrity, something that she became known for, even if others didn’t necessarily agree with her views, many of which were unconventional for the time.

Ironically, despite the restrictions she faced, music actually became a form of therapy for O’Connor, a liberating experience to express herself and to help her heal. O’Connor said that some of her edgier material proved especially helpful, that it gave her an opportunity to do what she really wanted to do most – scream. On some level, she must have believed that the pain she endured early on in life was something that didn’t serve her as she got older and that such strong emotionally charged artistic outbursts were an effective way to offload that anguish.

This was all part of O’Connor being true to herself and her beliefs. And expressions of this outlook became apparent in her outspoken views in many areas of her life – politics, social policies and practices, and even her own appearance. O’Connor’s famous shaved head, for example, arose in response to pressure from her record label, which tried to strong-arm her into adopting the flashy girly look of other successful ʼ80s pop stars like Madonna. That wasn’t O’Connor’s style, not at all reflective of her personal sensibilities. So, to counter that pressure, she took a razor to her scalp and created the look that became her signature appearance, one that was far ahead of its time and has influenced artists and popular culture ever since.

But pressures involving O’Connor’s appearance didn’t stop there. At the time her first LP was getting ready for release, O’Connor was pregnant with her first child, a development that became a big concern for the record company in designing the album cover. Officials at her label even went so far as to suggest that she terminate the pregnancy for the sake of appearances, a request she flatly refused. She agreed to album cover photography that concealed her baby bump, but there was no way she was going to give up her child for the sake of her record company’s discomfort with her condition.

O’Connor wasn’t afraid to take on the policies and practices in her own industry, either. For example, when the Grammy Awards refused to include rap music as a legitimate, viable category worthy of recognition, artists like Public Enemy refused to attend the ceremony. O’Connor, in turn, showed her support for her fellow artists by performing on the awards broadcast with Public Enemy’s logo tattooed on her scalp, an act that drew considerable attention to the plight of these overlooked musicians.

By taking these defiant stances, O’Connor was cautioned not to push these matters too far, as they were seen as jeopardizing her career as a pop star. But she often responded by saying that she didn’t care about that. She claimed that she made music for the sheer elation of the experience, one of the purest expressions of the joy and power of creation, adding that, if all of her success were to suddenly disappear, it wouldn’t matter to her, because that was not her reason for doing what she did.

Metaphysically speaking, that viewpoint itself represents a belief, one just as capable of yielding a bona fide manifestation as valid as any other. And, given how events played out in her life and career, that’s precisely what happened. However, as evidenced by what unfolded after her so-called fall from grace, O’Connor was undeterred in pursuing her primary goal – continuing to record and perform, even if not with the same level of notoriety and public visibility apparent when she was at the peak of her career. While much of the public is aware of her first three albums, they were not her only recordings; she has since gone on to record eight more albums, and she has been touring throughout the years since the incidents that drained her of her popularity. This is apparent in the film through footage from a recent concert performance in which she delivers a heartfelt rendition of a song titled “Thank You for Hearing Me.” Though written in 1994, this piece has become an obvious thank you to fans who have stayed with her and to the backers who faithfully supported her outspoken views, many of which have become widely accepted today and have even led to policy changes in government and the Church.

By holding fast to her beliefs, O’Connor has seen her vision materialize. One can’t help but think it must provide her with a sense of vindication. But she’s not been one to gloat now that such measures as greater rights for women and the LGBTQ+ community have been enacted in her native Ireland. The same is true of the approval of abortion rights on the Emerald Isle, which once had some of the world’s strictest laws in this regard. Indeed, in light of the changes, one can’t help but wonder whether these reforms would have ever come to pass had it not been for her steadfast conviction in her beliefs and their widespread public expression.

These developments illustrate how O’Connor was willing to become more than just another pop artist; she became an unapologetic activist, too. But the two were not mutually exclusive. Having developed a wide following through her music, O’Connor established a platform to make her voice heard – and not just for her singing. She used her beliefs in truly creative ways that ended up giving us not only memorable music, but also new ideas that have changed the world, most of which many would argue are for the better.

Still, many of her friends and supporters can’t help but believe that O’Connor got a raw deal in response to making her views known. While hindsight is indeed 20/20, many backers have suggested that the criticisms heaped upon her represented an overreaction, even by the standards of the time. As the film shows, she was subjected to severe ridicule and mockery, including in high-profile outlets, such as the show that once warmly welcomed her, Saturday Night Live. However, O’Connor waxes philosophically about all this, too. In one of her more astute observations in the film, she says of her experience, “They tried to bury me, but they didn’t realize I was a seed.”

O’Connor’s gestures were widely seen as acts of career suicide, but none of them fazed her, given that she couldn’t in good conscience stay silent. That kind of courage is often a rare commodity in almost any age, but that seems especially true these days. Which is why director Kathryn Ferguson’s documentary is such an important piece of filmmaking for these times. Even though O’Connor may have expressed views that were unpopular, she nevertheless had the inspiring courage of her convictions to make her feelings known and to carry her through the dark days that ensued. We could all learn a lot from her and from this offering given what we’re up against on so many fronts these days.

O’Connor’s life and work is detailed through a wealth of archive material, including ample performance footage and clips from her music videos. Observations from the artist and those who knew and worked with her augment this content but primarily through voice-over interviews that complement the historical imagery. Despite these strengths, however, some have criticized the film for not presenting a more complete picture of its subject, most notably her life and career from the early 1990s onward, a contention that, admittedly, has some merit. Some have also disparaged the picture for its absence of a recording of “Nothing Compares 2 U,” handily O’Connor’s most successful release. However, the film’s closing credits note that this piece was not included due to a rights issue in which the Prince Estate refused to grant permission to use the song (for reasons that aren’t specified). That’s unfortunate, given the prominent role this work plays in O’Connor’s career, but the picture attempts to make up for this by incorporating images from the song’s music video (but without the backing soundtrack).

Fortunately, “Nothing Compares” has not gone without its share of recognition. The film was nominated for the World Cinema (Documentary) Grand Jury Prize at this year’s Sundance Film Festival, a notable accomplishment, to be sure. It would be gratifying to see this offering earn additional accolades as awards season plays out. The film is currently playing on the Showtime cable TV network and the Showtime Anytime streaming service.

Even though O’Connor may have faded into relative obscurity over time, her music lives on. It’s unfortunate, though, that much of her body of work has gone unrecognized. However, we can take comfort that the same can’t be said of her views and the impact they’ve had in helping to reshape society. She truly was ahead of her time in so many ways, and this film makes that loud and clear. And, as the film so capably shows, in the end, when it comes to Sinéad O’Connor, nothing truly compares to her.

Copyright © 2022, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.