‘Being Mary Tyler Moore’ surveys an icon’s life and work

“Being Mary Tyler Moore” (2023). Cast: Voiceover Interviews and Observations/Archive Footage/Archive Voiceover Interviews and Observations: Mary Tyler Moore, James L. Brooks, Allan Burns, Treva Silverman, Lena Waithe, Robert Levine, Dick Van Dyke, Carl Reiner, Morey Amsterdam, Rose Marie, Larry Mathews, Ann Morgan Guilbert, Jerry Paris, Richard Deacon, Danny Thomas, Bill Persky, Sid Caesar, Nanette Fabray, Edward Asner, Betty White, Valerie Harper, Cloris Leachman, Ted Knight, Gavin MacLeod, Georgia Engel, Robert Redford, Donald Sutherland, Timothy Hutton, Michael Lindsay-Hogg, David Letterman, Dinah Shore, Rona Barrett, Oprah Winfrey, David Susskind, Dick Cavett, Katie Couric, James Lipton, Norman Lear, James Burrows, Fred Silverman, Lucille Ball, Julia Louis-Dreyfus, Bernadette Peters, Reese Witherspoon, Phylicia Rashad, Rosie O’Donnell, Rob Reiner, Joel Grey, Beverly Sanders, Julie Andrews, Elvis Presley, Danny Kaye, David Janssen, Beatrice Arthur, Conrad Bain, Marlo Thomas, Gloria Steinem, Betty Friedan, Betty Ford, Grant Tinker, John Tinker, Ronda Rich Tinker, Richard Meeker Jr., George Tyler Moore, Marjorie Tyler Moore, John Moore, Elizabeth Moore. Director: James Adolphus. Screenplay: James L. Brooks, Allan Burns, Susan Silver and Treva Silverman. Web site. Trailer.

I find it curious how often many of us think of the everyday lives of well-known actors and actresses as being virtually identical to the parts they play in movies and on television. These performers are so convincing in their roles that countless viewers tend to believe their on-screen and off-screen personas are virtually indistinguishable. However, when we examine the credibility of that idea, many of us can’t help but come to the conclusion that this notion is patently ludicrous, yet the memorable nature of their portrayals is so strong that we often have difficulty shaking that belief. Seeing these individuals for who they really are when they’re not on camera can be a challenging sell, but one film that does an excellent job of examining, but separating, the personal and the professional can be found in the insightful new HBO documentary, “Being Mary Tyler Moore.”

Moore’s characters became so associated with the actress’s performances that audiences saw her as Laura Petrie and Mary Richards. In fact, during and after her first TV role, many viewers sincerely believed that she and television husband Dick Van Dyke were actually married in real life. And later, as Mary Richards, fans of the show believed that Moore was the modern, single, career-oriented woman that she portrayed when, in fact, she was a happily married wife and mother.

So how closely did Mary Tyler Moore the person reflect the characters she played? As this documentary reveals, there were many similarities but also plenty of differences, many of which she kept carefully concealed. As a resolutely private individual, she rarely let those aspects of her life show during the early days of her career, keeping them from interfering with her professional life. Not long after her second TV series ended, she endured a variety of difficulties, including a sometimes-troubled relationship with her parents, two divorces, a miscarriage and an ongoing battle with type 1 diabetes. And, shortly thereafter, she experienced the loss of her only son in a gun shot accident, the untimely deaths of her two younger siblings and a bout with alcohol abuse that landed her at the Betty Ford Clinic. None of these ordeals were the kinds of events that viewers thought someone as sweet and lovable as “Mary” would have to endure.

Not long after The Mary Tyler Moore Show went off the air, the actress’s life went through some significant changes. She divorced from her second husband, TV producer Grant Tinker, and moved from Los Angeles to New York. Moore found the changes challenging but liberating. She saw this as an opportunity to stretch as an artist and as an individual. She took on different roles, such as that of icy middle-aged mother Beth Jarrett in the dark domestic drama “Ordinary People” (1980), for which she received a well-deserved Oscar nomination, and as quadriplegic sculptor Claire Harrison in a Broadway production of the right to die drama Whose Life Is It Anyway? (1980), a portrayal that earned her a special Tony Award. These projects not only allowed Moore to expand her range as an actress, but they also served as a de facto form of art therapy, helping her to heal from the tragedies she suffered and making it possible for her to open up more about them. The world was at last beginning to see that there was more to Mary than “Mary.”

The film brings these matters to light in a candid but respectful manner, enabling viewers to see Moore in a brighter light than perhaps ever before. In some ways, it evokes a strong sense of empathy for the actress, especially among those who may have never known any of these particulars about her life. Many audience members may indeed respond with a pronounced “We never knew” reaction, especially if they’ve long continued to believe that the actress was a mere reflection of her characters.

The impact of this carries many implications. For starters, the film makes clear that we’re more than just monodimensional beings – even actors and actresses. We might not always reveal all of the various sides of ourselves, which, of course, is our prerogative. However, we should be aware of the consequences of this practice, both in terms of the pain it can cause by keeping it bottled up and in keeping others – especially those who want to help – from seeing the real us.

Second, Moore’s accomplishments reveal the power connected with generating and sustaining impressions about her believability as evidenced by the indelible impact her performances left on so many of her fans for so long. At its heart, this is a prime example of make-believe at work, one that’s so convincing that its effects remained in place for years, a real tribute to an artist and her gift. At the same time, though, as admirable and memorable as these accomplishments might be, they can also become an artistic trap if left unaddressed – typecasting carried to an extreme.

Perhaps that was the impetus – either consciously or unconsciously — behind the change in direction Moore took after the seven-year run of her TV series. Her subsequent roles as Beth Jarrett and Claire Harrison, as well as other later parts, were so different from what preceded them that their depictions couldn’t help but prompt viewers into seeing Moore in a new light. Some of those who knew her well, in fact, observe in the film that these parts were in many ways more reflective of Moore as an individual than any of the other roles she played previously. Whatever the actual reason, though, we can be thankful that the actress decided to chart a new course so that we could see everything she had to offer as an artist and not remain stuck in the previously unchanging role of an endearing but perpetual lightweight. More importantly, however, this new direction also helped Moore become a new person, one who was more open, more free to be herself, a development that, one could argue, enabled her to grow as a performer and as an individual. And that’s something we can be thankful for, too, both for the sake of her own happiness and for the enjoyment she gave us as an entertainer.

Where Moore was concerned, the most significant beliefs she needed to address were those related to how open she was willing to be about her personal and professional choices. This, in turn, is arguably tied to underlying core beliefs associated with things like fear, confidence and a willingness to confront the unpleasant. And, as a number of the film’s interview segments with the actress reveal, she openly acknowledges that she never saw herself as a risk taker, undoubtedly what accounted for her reluctance to speak openly about her private life and the comparatively “safer” and more familiar choices of roles that she accepted during the early part of her career. But was that really the case?

Given her professional choices in her early career, Moore indeed took chances that represented big risks for the time, even if she didn’t necessarily recognize them as such. As Laura Petrie, for example, she portrayed a housewife who was unafraid of expressing her opinion, even to her husband, something that TV sitcoms (other than perhaps I Love Lucy) typically didn’t dare do at the time. She even helped establish women’s fashion trends at the time, regularly sporting her signature capri pants, a departure from the house dresses, pearls and full makeup worn by virtually all television housewives of the period.

Moore took even bigger chances as Mary Richards, a single career woman who was more content with developing her professional life as a local TV news producer than settling down and getting married. In this way, Moore became something of a poster child for the women’s liberation movement in the 1970s, epitomizing the outlooks of many feminists of the time and encouraging those who may have once settled for more traditional options to look further afield when it came to their lives and choices. It was a role that Moore wasn’t always completely comfortable with as a married woman in real life, but she didn’t shy away from it, either, as someone who also pursued a professional life of her own while being a wife and mother.

However, by the time Moore went on to pursue new personal and professional choices after the end of The Mary Tyler Moore Show, something changed – her recognition of the fact that she could explore new avenues. She came to believe in the possibilities, and that shift enabled her capacity for taking risks to surface, which she began to exercise freely, as evidenced by her new roles and her entry into a new and loving marriage with third husband Robert Levine, a relationship that endured until the end of her life. She at last became conscious of an ability that was present all along; the difference now, though, was that she believed in it, a quality that was once consciously absent, despite ample evidence to the contrary in the outcomes she achieved.

From this point onward, Moore sought to stretch her capabilities, as evidenced in her work in “Ordinary People” and Whose Life Is It Anyway? But that venture didn’t stop with these projects. It also became apparent in her film work in “Six Weeks” (1982), the story of a mother dealing with the impending death of her young daughter, and “Flirting with Disaster” (1996), a screwball comedy in which a neurotic New York mother wrestles with her adopted son’s desire to find his biological parents, both of which are touched on briefly in the documentary. Admittedly, not all of Moore’s professional choices panned out as successfully as hoped for during this later phase of her career (and, thankfully, this film respectfully disregards them), but her actions during this time show how we’ll never know what we’re capable of if we’re unwilling to overcome the fears and limitations that hold us back and to embrace beliefs that enable us to take chances that could pay big dividends. Indeed, nothing ventured, nothing gained.

To a great degree, this depends on our ability to view ourselves authentically, to see ourselves for who we really are and to envision the possibilities that spring forth from such an examination. And, as noted earlier, that relates to our capacity for picturing ourselves as the inherently multidimensional beings that we are, individuals who are capable of far more than we may initially believe. This is evidenced by the clips of Moore’s various performances that are included in the film. In scenes from “Ordinary People,” for example, we see Moore in full-out ice princess mode – cold, judgmental, close-minded and thoroughly in denial of her circumstances. By contrast, in “Chuckles Bites the Dust” (1975) from The Mary Tyler Moore Show, an episode in which Mary takes a self-righteous stand about what she sees as her co-workers’ inappropriate joking about the untimely death of a clown from a local children’s television program, the actress delivers a master class in comedic acting, a performance that helped earn the show TV Guide’s designation as the best television comedy episode of all time. Through these two performances alone, we see Moore’s extensive range on display, showing off her multidimensional nature as an entertainer, one who could truly do it all, simply by believing in herself and her abilities.

At the risk of sounding like I’m gushing, this documentary effectively illustrates the depth and versatility of this performer’s talents, as well as her capacity for courage in facing and addressing her many personal challenges. We come to see her as more than just the affable television characters she portrayed. Instead, we see her as someone whose gifts were often underappreciated in light of what she had to offer. It’s no wonder she captured the 2012 Screen Actors Guild Lifetime Achievement Award. Her peers saw what she possessed and honored her accordingly. Here’s hoping this film helps to do the same for a wider audience, especially among those less familiar with her work – and legacy.

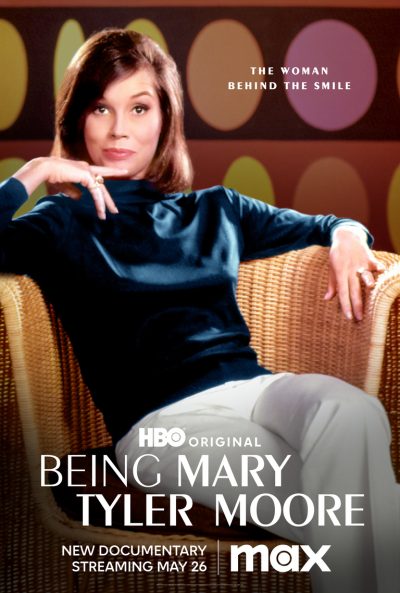

To say that iconic actress/singer/dancer/comedienne Mary Tyler Moore was a gifted, complicated, reserved, often-misunderstood individual is indeed an understatement. However, director James Adolphus’s new HBO documentary presents a reverent, insightful and respectfully candid biography of the famed star of TV, stage and screen, showing off Moore in all of her magnificent undertakings. The film chronicles how she changed the face of television comedy and demonstrated a degree of acting versatility rarely seen among many Hollywood artists. It also illustrates her ability to survive under harrowing conditions, many of which touched her life in ways largely unbeknownst to the public. The fighter within her found ways to work through the anguish in her professional missteps and personal ordeals and helped her emerge triumphantly virtually every time. The filmmaker tells Moore’s complex, moving and inspiring story with an array of clips from her work, archive interview footage with renowned journalists and celebrities, and ample voiceover observations from those who knew her and those who admired her for the example she set for later generations of women and acting professionals. The narrative is admittedly somewhat straightforward and formulaic, seldom breaking out of the boundaries of typical documentary filmmaking, but it nonetheless presents an excellent composite of images and insights into the life and work of a legend, one that’s assured to depict her in a new light and could well introduce her to a new generation of fans who may not have previously been aware of her many accomplishments. Take a bow, Mary.

Copyright © 2023, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.