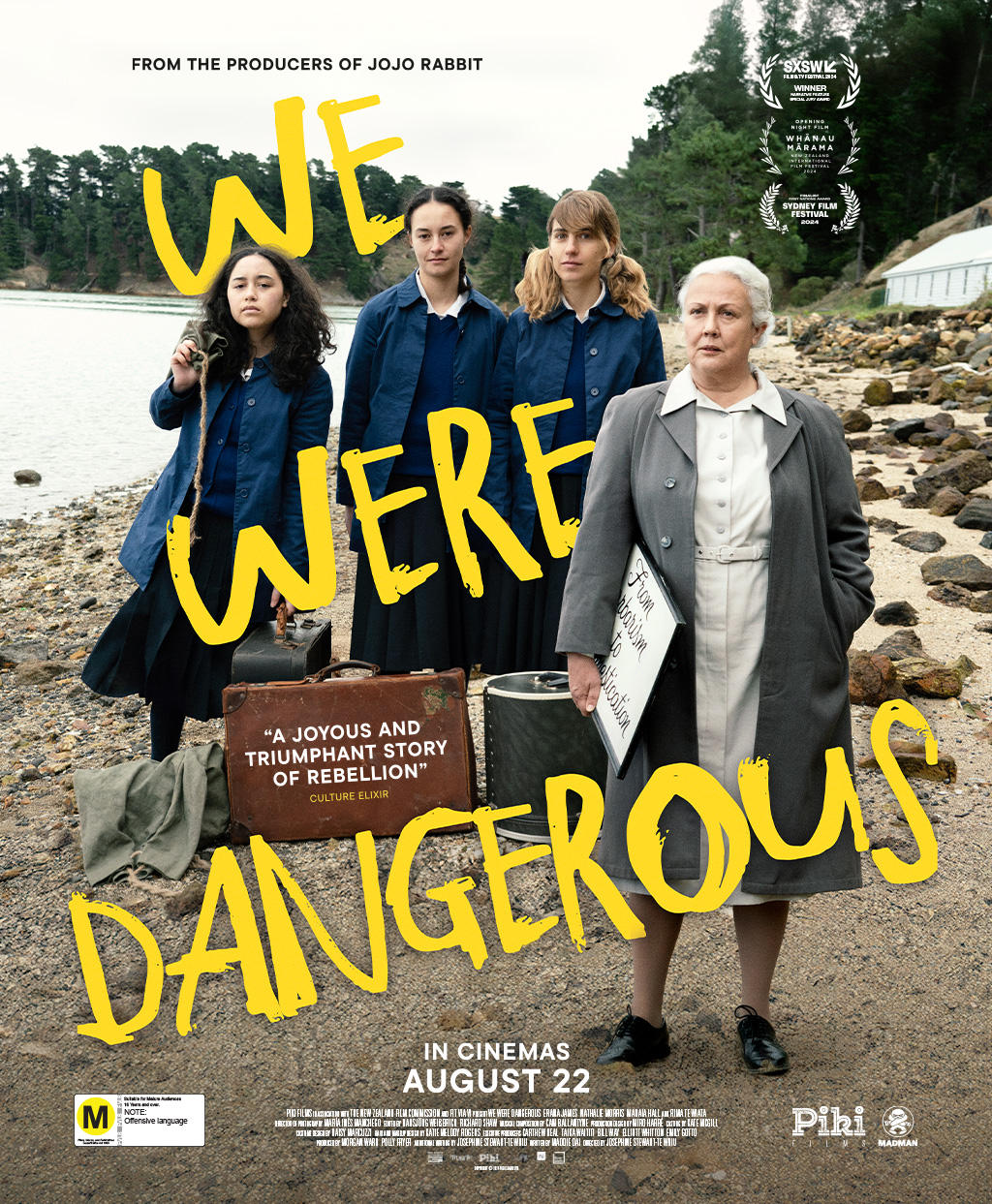

‘We Were Dangerous’ celebrates the inner rebel

“We Were Dangerous” (2024 production, 2025 release). Cast: Erana James, Manaia Hall, Nathalie Morris, Rima Te Wiata, Stephen Tamarapa, Hillary Moulder, Portia Regan, Rosie Leishman, Malena Taurima, Stephen Lovatt, Barry de Lore, Luanne Gordon, Cian Parker, Manaia May. Director: Josephine Stewart-Te Whiu. Screenplay: Maddie Dai and Josephine Stewart-Te Whiu. Web site. Trailer.

Such was the case in 1954 New Zealand in this film about a government-run girls’ reform school for an assorted collection of young women who had been unreservedly labeled social and sexual “deviants.” The facility, established out of the state’s abundance of concern to help rehabilitate them and alter their supposedly wayward behavior, was firmly committed to the goal of transforming them into proper ladies suitable for marriage and motherhood. This was accomplished by strictly following a three-step program of “Christianize, civilize and assimilate” (with a particularly heavy emphasis on the first step). However, when several residents engaged in behavior that was seen as stepping over the line of acceptability, government officials charged with their oversight came down hard on them and the school’s staff. They believed that both the girls and their caretakers had to pay the price for what happened. And so, in the wake of this “scandalous” incident, a drastic change was hurriedly implemented.

In an effort to prevent future recurrences of such intolerable incidents, a dozen of the facility’s residents and several key staff members were summarily relocated to a remote island that was once a leper colony and home to other assorted misfits and undesirables. Their new home, which had been dubbed the Te Motu School for Incorrigible and Delinquent Girls, consisted of an assortment of rundown cabins in need of extensive repair, a task assigned to the girls upon their arrival. And, when they weren’t doing reconstruction work, they performed an array of chores and attended classes on everything from the three Rs to Bible study to proper womanly etiquette. But, no matter how much work, discipline and schooling the girls were subjected to, the administrators’ hopes for flawless complicity with their demands never quite panned out, transgressions that naturally necessitated various forms of punishment. At some point, though, the impact of such retributive treatment began wearing thin, especially as the residents began tapping into the power of their inner rebels. Of course, such belligerent responses prompted even harsher, more sinister, more disturbing measures that, in turn, led to even more combative resident reactions that carried greater consequences.

Narrated by the school’s stern, calculating, insincere head matron (Rima Te Wiata), the film chronicles the diverse life experiences and backgrounds of the girls, many of which are presented anecdotally and in flashbacks. Some of these incidents are wryly humorous (even if quaintly and wholly archaic by today’s standards), while others are sad, tragic and profoundly unfair. And, as these events unfold and grow progressively more dire, the more troubling matters prompt three of the island’s residents, Nellie (Erana James), Daisy (Manaia Hall) and Louisa (Nathalie Morris), to take cleverly clandestine yet courageously assertive steps to fight back to protect themselves and their peers from a potentially catastrophic and appalling fate. Indeed, there’s no keeping down powerful forces to be reckoned with, as they’re sure to become truly “dangerous” when backed into a corner and their inner radicals are summoned forth.

This is why suppressing the rebels among us – and within us – can ultimately end up causing more harm than good. Ignoring or squelching their out-of-the-box beliefs could delay or prevent the development of those aforementioned innovations. And, if so, where would that leave us? Because of that, their unconventional outlooks and the intents that emerge from them should be nurtured and encouraged, not dismissed or shoved aside to preserve what could essentially amount to stagnation and a lack of meaningful progress. To avoid that outcome, then, we should celebrate the inner rebel in its efforts to help us discover ourselves, our capabilities and our capacity for creativity. That’s especially true if allowing such developments causes no harm to anyone or anything else; it’s simply a case of making it possible for unenvisioned and unexpressed ideas and aspects of ourselves to surface and to see what they can yield.

Those bold innovations get their starts with our beliefs, and their importance should not be underestimated in light of the role they play in the manifestation of our existence, a product of the conscious creation process, the philosophy that makes such outcomes possible. It’s unclear how many of the characters in this film (or any of us in general) are aware of this school of thought, but it’s a way of thinking that should not be ignored given what it can ultimately materialize to make our world better, more enjoyable and more fulfilling. And the kind of tolerance called for in this is precisely what the girls in this story need if they are to find themselves and allow their inner beings to blossom into full flower.

The open-mindedness necessary to enable our inner rebels to thrive could ultimately prove useful in fostering the emergence of our innate reserves of creativity and resourcefulness, and there’s no telling what could arise from the expression of such unconventional thinking and beliefs. But, even if they don’t lead to the invention of the next best thing, if nothing else, allowing such radical notions could nevertheless contribute to maximizing our personal satisfaction and enjoyment of life. And why on earth would we want to try and hinder that?

To that end, then, a key question that the gatekeepers charged with containing our rebellious outlooks must ask themselves is, what is to be gained from willfully inhibiting these beliefs and perspectives? This is relevant when it comes to sanctioning some of the behaviors exhibited by the girls in this film. Many of them, for instance, have an interest in rock ʼn roll, which was just beginning to emerge as a new musical form at the time, yet their affinity for it was seriously frowned upon as antisocial and un-ladylike. But, in all honesty, who was being hurt by this? The girls obviously weren’t, as they had an inherent attraction to it. And, as for those around them, how were they being harmed? And what impact, if any, was their interest in this music having on them?

A similar argument could be made over Louisa’s curiosity in same-sex romance. Her innocent exploration of this form of sexuality got her branded as a rebellious deviant when she was still living with her uptight, ultra-conservative family, leading to her immediate expulsion from the household and subsequent transfer to reform school. But, again, who was being harmed by this behavior? And why was it being put down if that was her natural inclination? What impact would her exploration of this aspect of her true self have on society other than possibly removing one potential mother from its future ranks – and perhaps needlessly creating an unhappy soul in the process?

These circumstances, in turn, raise important questions about the overreaching reactions to these behaviors by government officials and school administrators. Why were they so unnerved by them? For all practical purposes, they were responding out of fear, and fear is, in itself, a form of belief. But what was posing such a threat to prompt a fearful reaction like this, and why did they feel so compelled to contain it? Were they afraid this trend would get out of hand? Did they fear that its growth would result in the loss of the lives with which they had grown so comfortable? Or were they afraid that the surfacing of the girls’ inner rebels was reflective of something that might eventually happen to them, too? These conditions certainly gave them much to consider – and to reflect upon, especially when it comes to seeing how easy it is to let molehills needlessly swell to the size of mountains.

The foregoing consequences thus illustrate the value in recognizing, understanding and supporting the rebels that likely reside within each of us, be their impact ultimately great or small. We should respect the beliefs that underlie those attitudes and enable them to prosper to reach their full potential. There’s much to be gained and likely little to be lost by doing so, especially since the prospect of danger is probably minimal at best. Indeed, long live the rebel!

Writer-director Josephine Stewart-Te Whiu’s debut feature sheds valuable light on these questions in telling an engaging, economically paced coming of age tale said to be inspired by actual events. The “life at a rigidly run girls’ reform school” storyline might be seen by some as rather episodic, formulaic and even trite, but those shortcomings are handily overcome here by narrative elements that distinguish this particular offering from others of its kind, namely, its superb writing, excellent character development (especially among the residents and colorful supporting cast members), a well-balanced and deftly combined mix of comedy and drama, and gorgeous location cinematography. Then there are the outstanding performances of the ensemble, most notably James, Morris, Hall (who had no prior acting experience and auditioned for her role on a lark), and, most of all, Te Wiata, who delivers a truly award-worthy portrayal. What’s most impressive here, though, is the work of the production’s first-time feature filmmaker, a promising new voice in the field whose initial release bodes well for a bright big screen future. Indeed, “We Were Dangerous” is one of those delightful arthouse gems that has largely flown under the radar but has quietly earned a well-deserved reputation as the inspiring work of a new talent who has managed to successfully knock it out of the park on her first try. Catch this one in limited theatrical release or online; otherwise, report to the matron immediately.

It’s easy to decry the so-called danger of the rebel, but it’s far less common that we celebrate its potential for inventiveness and creativity. And that’s a shame, considering how seriously its possible contributions can be unwittingly sold short. Rather than roundly dismissing the radical, we should take the time to see what it has to say to determine if it offers any meaningful benefit before we take it to task or act on it. Who knows what untapped greatness might reside within its essence if we summarily dispense with it and fail to consider what it might have to offer not only its host, but also the rest of society at large. To do less is truly shortsighted – and a potentially bigger danger than any rebel element might itself ultimately pose.

Copyright © 2025, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.