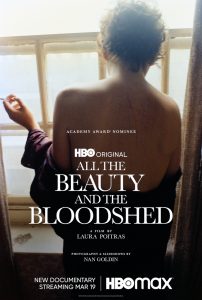

“All the Beauty and the Bloodshed”

(USA)

Metacritic (5/10), Letterboxd (2.5/5), Imdb.com (5/10)

Have you ever watched a movie that feels like it could readily be split into two separate pictures? Such is the case – and the problem – with this latest offering from documentarian Laura Poitras. The film’s dual tracks showcase (1) the campaigns of the activist group P.A.I.N. (Prescription Addiction Intervention Now) formed by artist/photographer Nan Goldin to expose the greed-mongering atrocities of Purdue Pharma, manufacturer of the highly addictive opioid painkiller OxyContin, and the Sackler family, the principals behind this organization, and (2) the life, career and addiction struggle of the artist herself. In particular, the film follows P.A.I.N.’s activities to protest the Sacklers’ efforts to deflect attention away from their nefarious behavior by making huge donations to the arts community (including many notable museums) by staging highly vocal, highly visible demonstrations at those facilities to draw attention to this issue, particularly the mounting number of deaths that have resulted from addiction to this prescription drug. Simultaneously, the documentary charts Goldin’s journey through her colorful, prolific and high-profile career, which eventually led to a period of addiction (whose origins are never really made clear) that nearly killed her. While each of these narrative tracks is explored capably in themselves, they never quite mesh into a complete, coherent whole. Goldin’s struggle with the opioid serves as an anemic lynchpin that attempts to connect these two story threads. But the central nexus isn’t strong enough to link them effectively, each of which individually could have served as the bases for films all unto themselves – and that ultimately would have each been more engaging and compelling than this underdeveloped hybrid product, which often feels like it’s stretching to find its true footing. The work of P.A.I.N. is arguably the stronger of the two stories, and focusing on that aspect of the story by itself would have made for a better and much more impactful picture. Unfortunately, that’s not how matters play out, a disappointment given that it deals with such an important subject. Providing the proper focus for her projects seems to be an ongoing issue for the filmmaker, one that previously became apparent in her award-winning but underwhelming real-time documentary “Citizenfour” (2014) about the revelations of Edward Snowden, a shortcoming that, regrettably, has been repeated here. I find that frustrating, especially since this meandering offering, like its predecessor, has been showered with considerable undeserved praise, including an Oscar nomination for best documentary feature. Poitras clearly has a lot to say, but it’s unfortunate that she has still yet to figure out how to say it more effectively than she does.

Leave A Comment