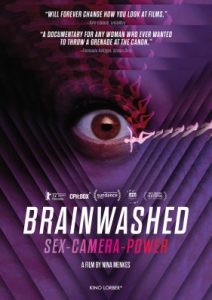

“Brainwashed: Sex-Camera-Power”

(USA)

Metacritic (1/10), Letterboxd (0.5/5), Imdb.com (1/10)

The objectification of women is certainly a crucial issue that needs to be dealt with. However, if awareness of the problem is to be raised, it definitely requires a better film than this specious, sloppy, cherry-picked offering. Based on a TED Talk-style presentation titled “Sex and Power: The Visual Language of Film” by director Nina Menkes, the filmmaker makes the argument that objectification is a result of the way male-female interactions are typically staged in movies, a practice that reflects a phenomenon referred to as “the male gaze,” a leering stare that, in turn, is responsible for things like employment discrimination in the entertainment industry and increased incidents of sexual harassment and assault. And, because films “reinforce” this, as Menkes insists, they’re at fault for these troubling problems, a product that’s a direct result of the decision-makers in the male-dominated movie industry. One might say this is indeed a plausible hypothesis given the proliferation of these filming techniques in motion pictures. There’s just one problem with this theory – it’s largely preposterous. To begin with, “the male gaze” has been around a lot longer than the movie business (like, say, all the way back to prehistoric times), a notion implied just by the very idea that movies are said to “reinforce” this practice, suggesting its earlier appearance in the history of the species. Second, males invoke the gaze with more than just women (just ask almost any gay man who’s checking out another male at a bar or community event). And, third, this practice is engaged in by men who never go to the cinema (especially many of the somewhat obscure titles the director cites as examples to allegedly prove her point). The argument is further undermined by some of the film clips she uses in a failed attempt to add credence to her contention – pictures that were directed by women that incorporate some of the same filming techniques she criticizes. She even takes issue with the staging of a scene in the film “Bombshell” (2019), a picture whose very intent is chronicling the sexual harassment scandal at FOX News involving power broker Roger Ailes, lambasting it for employing some of the same filming practices that this production was seeking to expose. Of course, to demonstrate how things should be done, Menkes taps a number of clips from her own films (titles that I, as an avid cinephile, have never heard of and that include content similar to what she’s criticizing, even if filmed somewhat differently). (Ah, yes, nothing like a little blatantly shameless self-promotion to help prove your point.) To its credit, this documentary draws worthy attention to the issues of objectification, employment discrimination in Hollywood and sexual abuse, but this film is a sorry representative of those issues, all of which are addressed much more effectively by releases like “This Changes Everything” (2018) and “She Said” (2022). Those other films are much more interesting than this snooze, too, a clunky offering that plays more like a seminar than a movie. It’s truly ironic that Menkes asserts men have become brainwashed into this way of thinking by what they see in the movies, especially given that the only one who seems to have been brainwashed here is the director herself by her own material.

Leave A Comment