‘The Post’ examines what it takes to do the right thing

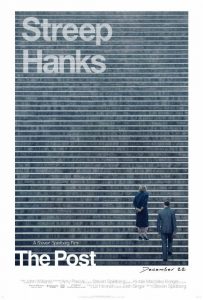

“The Post” (2017). Cast: Meryl Streep, Tom Hanks, Sarah Paulson, Bob Odenkirk, Tracy Letts, Bradley Whitford, Bruce Greenwood, Matthew Rhys, Alison Brie, Carrie Coon, Jesse Plemons, Michael Stuhlbarg, Justin Swain, Curzon Dobell. Director: Steven Spielberg. Screenplay: Liz Hannah and Josh Singer. Web site. Trailer.

When faced with hard choices, we may not know which way to turn. That’s especially true when all of our options appear problematic. Deciding which of the seemingly troublesome outcomes will prove least onerous can try our patience and test our resolve. At the same time, though, such scenarios can sharpen our scrutiny skills, especially when it comes to drawing upon our intuition and integrity to arrive at an amenable solution. So it was for a group of media professionals who found themselves with their backs up against the wall as seen in the new fact-based journalism drama, “The Post.”

In 1971, The Washington Post was going through a bumpy transition period. The family-owned newspaper, managed by publisher Kay Graham (Meryl Streep), was in the process of going public to improve its financial position. But, to help make the publication a more attractive investment option, the paper also needed to look at upping its editorial profile, one more in line with the first-class reporting reputation it was seeking to cultivate, a responsibility assumed by editor Ben Bradlee (Tom Hanks). This was vital in light of the changing journalism marketplace, with more major newspapers, like The New York Times, taking on more of a national – and not just a local – presence. If the Post didn’t act, it could be left in the dust by other publications, threatening the company’s future.

The opportunity to advance the paper’s coverage came with the release of the Pentagon Papers, a 7,000-page collection of covert documents detailing the U.S. role in Vietnam – not just during the war but in the two decades preceding it, going as far back as the Truman administration. Through this disclosure by military analyst Daniel Ellsberg (Matthew Rhys), it became apparent that American interference in Vietnamese affairs was pervasive, with extensive involvement in the Asian nation’s politics, economics and society. The damning disclosure also documented the futility underlying the U.S. war effort, a campaign that continued despite insider knowledge of this inherent problem and increasingly vocal domestic disapproval of the conflict.

Washington Post publisher Kay Graham (Meryl Streep, right) and editor Ben Bradlee (Tom Hanks, left) discuss the paper’s precarious future in director Steven Spielberg’s latest, “The Post.” Photo by Nick Tavernise, courtesy © Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation and Storyteller Distribution Co. LLC.

The story was initially broken by New York Times reporter Neil Sheehan (Justin Swain). However, given the bombshell nature of these revelations, the Nixon administration quickly came down hard on the Times, imposing an injunction against it from publishing any further material from the secret report, given that it was allegedly leaked in violation of the federal Espionage Act. With the Times’s hands tied, this opened the door for the Post, especially when Ellsberg was identified as the source of the leak: As a former colleague of Post assistant managing editor Ben Bagdikian (Bob Odenkirk), Ellsberg found a new outlet for making additional disclosures.

Needless to say, given the magnitude of the story, Bradlee and Bagdikian jumped at the chance to pick up the gauntlet and continue publishing articles about the Pentagon Papers. However, considering that the Post’s source was the same as that of the Times, the paper soon found itself in the same position as its New York counterpart: If it published, it would be in violation of the same injunction that was now hampering the Times’s efforts.

This presented an enormous ethical dilemma for Graham. As someone who found herself in a position in which she never expected to be – she took over management of the Post after the unexpected death of her husband – and given the financial pressures on the business, she had to make the hard decision of whether or not to publish. If she allowed the Post to pick up where the Times left off, she ran the risk of prosecution and attendant penalties (including incarceration), not to mention the financial collapse of the paper that would almost assuredly follow. At the same time, if she green-lighted her staff’s plans, she would help raise the Post’s editorial reputation, a move that would also likely cast her in the light of a confirmed First Amendment champion (especially if courts ruled in the paper’s favor). Graham thus faced quite a high-stakes decision.

Ben Bradlee (Tom Hanks) faces tough editorial decisions for his publication, The Washington Post, in “The Post.” Photo by Nick Tavernise, courtesy © Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation and Storyteller Distribution Co. LLC.

For Graham, personal considerations were also on the line. As a longtime friend and confidante of former Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara (Bruce Greenwood), Graham had to weigh this relationship with the publishing dilemma she now faced. Having personally authorized the ramp-up of the Vietnam War during his tenure in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations, McNamara figured largely in the Pentagon Papers disclosures, revelations that painted him in a very different light from the person Graham thought she knew. Printing exposés about McNamara’s involvement would undoubtedly strain the bond between the two friends. But, as the former Secretary strongly cautioned, publishing further excerpts from the clandestine documents would bring the full weight of U.S. government down on the Post – and Graham.

With these circumstances in place, the stage was thus set for a high-profile showdown, one that would find its way to the U.S. Supreme Court. But, as significant as the stakes were for the paper, its owner and its staff, there was much more in jeopardy, especially where freedom of the press considerations and personal relationships were concerned. The events at the heart of this very public and personal drama thus effectively demonstrate what it means to take a stand, to do the right thing, even in the face of seemingly long odds and potentially devastating consequences. They provide the makings of a powerful, inspiring message to those staring down demanding and far-reaching challenges, circumstances where the stakes are a lot bigger than those of the principal individuals and organizations involved.

Wherever we end up, though, depends on what we seek to manifest, a product of our thoughts, beliefs and intents, the building blocks of the conscious creation process, the means by which we bring our reality into being. And what emerges through those thoughts, beliefs and intents depends on the input provided by our intellect and intuition, the forces that shape those cornerstones that lay the foundation for our existence. Learning how to tap both of those sources is thus crucial to arriving at the outcomes we look to achieve.

But what happens when we’re unsure how to proceed under certain circumstances? How can we determine what to do? It’s at those times that we need to draw upon all of our metaphysical resources as much as possible.

When it comes to accessing our intellect, most of us know how to proceed. But, as for our intuition, we’re often at a loss; we tend to be less experienced in drawing upon it, because we generally don’t trust it, seeing it as illogical or irrational, flying in the face of our intellect. Nevertheless, its input is just as significant, even if it superficially doesn’t always seem to make sense.

Washington Post publisher Kay Graham (Meryl Streep) faces ethical dilemmas, both personally and professionally, in the new, fact-based journalism drama, “The Post.” Photo by Nick Tavernise, courtesy © Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation and Storyteller Distribution Co. LLC.

When the Post was facing its publish/don’t publish dilemma, for example, Graham and Bradlee had to weigh the impact of their intellect and intuition. From an intellect standpoint, they were cautioned not proceed, that the likely consequences would be devastating. This message was reflected back in various ways, such as the threats coming from the Nixon administration, the injunction already enacted against the Times and the advice offered up by various advisors to the paper (Tracy Letts, Bradley Whitford, Jesse Plemons). At the same time, though, their intuition was urging them to move forward, to get the word out about the Pentagon Papers, because it would expose the decades-old exploits of the U.S. government, the truth about the country’s war efforts and the administration’s campaign to muzzle the press, considerations of greater importance than anything that might affect the paper and its principals. No matter how much they may have tried to downplay these concerns, they would continually reappear, nagging at them not to ignore the associated message.

This was arguably less of a concern for Bradlee than it was for Graham, given that telling the truth and getting the word out to the public were his primary job responsibilities as editor. It certainly helped that he had influences to remind him of this, such as Bagdikian’s presence, whose zealous encouragement to publish helped bolster his confidence in a decision to proceed. Graham, however, had other considerations to balance, such as the Post’s financial position; after all, concern about getting the word out would become a moot point if the paper were to go out of existence. At the same time, though, where would we be as a nation if we didn’t have a free press to tell the people the truth about what their government was doing, no matter how unsavory that truth might be? It was on that point that Graham found her way, especially as her intuition kept driving that message home, one that formed the basis of the beliefs she employed in bringing her reality into being – especially proceeding with publishing.

It’s hard to know if Graham and Bradlee consciously employed such metaphysical deliberation in their thought processes. But, when one examines how events played out, it’s easy to see that they made use of it, even if they weren’t aware of intentionally doing so. We can all be thankful for that, for it involved taking quite a risk – a leap of faith based on intuitional impulses that many of us might not be comfortable in relying upon for a decision as important as this. But, when it comes to doing the right thing, with so much riding on the outcome, we must make a concerted effort to bring about the desired result. Fortunately, we have the example set by Kay Graham and Ben Bradlee to help show us the way, and we shouldn’t be afraid to draw upon it when the need and circumstances arise.

Informal meetings between Washington Post publisher Kay Graham (Meryl Streep, right) and editor Ben Bradlee (Tom Hanks, left) often turn into profound discussions about the paper’s future in “The Post.” Photo by Nick Tavernise, courtesy © Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation and Storyteller Distribution Co. LLC.

Even by drawing upon all of our metaphysical wherewithal, as this scenario demonstrates, hard choices can still be extremely difficult to deal with, no matter how obvious the right decisions might appear to outside parties. But there are tools we can draw upon to help make matters go a little more easily. Drawing upon our sense of integrity, for instance, can prove invaluable. Since it requires us to get in touch with our truest, most authentic selves, that means we must tap into our most significant core beliefs, those that rest firmly on a bedrock formed from the input of our intellect and intuition. By doing so, we greatly increase the likelihood that we’re making wise choices, even if the face of the most difficult decisions.

Likewise, as noted above, there’s the matter of faith, not the kind typically associated with a religious context but in a personal, confidence-in-oneself sense. Trusting our decisions based on the foregoing process of analysis should provide us with a high degree of comfort as to how we’re proceeding. Putting stock in this notion can help us rest assured that we’re moving ahead as we’re supposed to.

Lastly, there’s the notion of value fulfillment, the conscious creation concept related to being our best, truest selves for the benefit of ourselves and those around us. If we bear this idea in mind as we go through the deliberation process, we can, again, feel confident that we’re progressing correctly. Of course, value fulfillment itself draws heavily upon the power of integrity and faith, so it stands to reason that its significance in effective conscious creation efforts should be plainly apparent, and its impact can be seen most readily when those hard choices land on our doorsteps.

After a somewhat slow, sometimes-belabored start in which the paper’s financial woes are detailed almost to excess, “The Post” thankfully finds its legs about 40 minutes in, at last taking off on a more engaging pace as it moves toward its uplifting (albeit predictably feel good) conclusion. It’s a film with a timely (though, one can’t help but cynically wonder, regrettably tardy) message about the state of journalism in an America presently besieged by corporate media consolidation and heavy-handed attempts to quash free speech. Streep and Hanks turn in adequate performances in their lead roles (though definitely far from their best), with the real stars shining in the supporting parts (particularly Odenkirk, Greenwood and Rhys). Given the current political climate, director Steven Spielberg’s latest is the right film with the right message that liberal Hollywood adores and loves to lavish with honors. It’s just too bad that it’s not a picture that fully lives up to that aspiration.

Despite its shortcomings, however, “The Post” has been extensively honored in this year’s award competitions, most recently with two Oscar nominations for best picture and actress (Streep). The film also captured three National Board of Review awards for best picture, actress (Streep) and actor (Hanks) and was named American Film Institute Movie of the Year. In addition, the picture earned six Golden Globe nominations (best dramatic picture, director, screenplay, score, dramatic actor, dramatic actress) and eight Critics Choice Award nods (best picture, director, original screenplay, score, editing, acting ensemble, actor, actress), though it took home no statues in either of these competitions.

Taking a stand is truly a noble act – but one that’s often fraught with great risk (and rewards). When up against such circumstances, we must weigh what’s at stake and the consequences of what each outcome might bring. Should we emerge victorious, however, we can look back and see just how meaningful our efforts prove to be.

Copyright © 2018, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

Leave A Comment