‘At Eternity’s Gate’ muses on the call to create

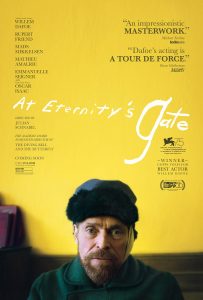

“At Eternity’s Gate” (2018). Cast: Willem Dafoe, Rupert Friend, Oscar Isaac, Mads Mikkelsen, Mathieu Amalric, Stella Schnabel, Vladimir Consigny, Emmanuelle Seigner, Lolita Chammah, Niels Arestrup, Anne Consigny, Amira Casar. Director: Julian Schnabel. Screenplay: Jean-Claude Carrière, Louise Kugelberg and Julian Schnabel. Web site. Trailer.

The power of creation is truly magnificent. Seeing intangible concepts materialize into tangible manifestations is a miraculous sight to behold. And it’s especially impressive when we consider the infinite range of possibilities that can be made real. However, for those of us who bring such outcomes into being, appreciating the range of what we can create can be overwhelming, perhaps even more than we can realistically handle. Getting a grip on such boundless possibilities could prove maddening, a challenge that confounded an accomplished painter who fought to bring his vision into being, a struggle chronicled in the new historical character study, “At Eternity’s Gate.”

Dutch post-impressionist painter Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890) (Willem Dafoe) led a difficult life. The expansively minded artist envisioned forms of expression that truly pushed boundaries of what was believed possible to achieve on canvas. He was able to conceive of images and styles never before dreamed of or attempted. And, with the encouragement of contemporaries like Paul Gauguin (Oscar Isaac), he earnestly sought to follow through on his vision.

However, van Gogh’s cutting-edge artistry was not well received, even in a supposedly progressive artistic mecca like Paris. His works were seen as too radical, even “disturbing,” and not even ardent supporters like Vincent’s brother, Theo (Rupert Friend), an art dealer, were able to successfully promote (or sell) his paintings. Consequently, at Gauguin’s urging, the misunderstood and underappreciated painter decided to pursue a fresh start in rural Arles in the south of France. This move was an attempt at providing him with ample sources of inspiration and new subject matter, a locale where he believed he could give life to his mission.

Dutch painter Vincent van Gogh (Willem Dafoe) moves from Paris to rural Arles in the south of France to seek new sources of subject matter and inspiration in director Julian Schnabel’s “At Eternity’s Gate.” Photo by Lily Gavin, courtesy of CBS Pictures.

Van Gogh’s relocation proved valuable when it came to providing him what he sought artistically; the sources of inspiration were everywhere in the people and landscapes. But, at the same time, the conservative, close-minded sensibilities of the locals caused him constant consternation. Not only was he criticized for his work, but he was also treated with open hostility for his unconventional creations, circumstances that made his struggle to fulfill his artistic vision ever more difficult. The situation improved for a time when Gauguin paid him a visit, but, when his peer announced plans to return to Paris, van Gogh descended into a form of madness, one that led him to inexplicably sever his ear.

Upon the recommendation of a compassionate physician (Vladimir Consigny), van Gogh entered treatment at a local mental institution. His time in confinement was meant to help him stabilize psychologically, particularly where defining his artistic sensibilities was concerned. He was allowed to paint during this time, and it was a period that proved to be quite prolific. But, in many ways, his tenure in the facility raised more questions than answering the ones he already had. With time to think under such controlled circumstances, he pondered theories of creativity, especially in terms of how they relate to the divine, the ultimate source of creation. And, even though he appeared calmer for having spent time in treatment, he was more perplexed than ever in terms of defining his vision and his relation to it.

Van Gogh’s thoughts on this subject were the topic of a profound conversation he had with a priest (Mads Mikkelsen) charged with deciding the painter’s fate. It was through this dialogue that the depth of Vincent’s feelings and insights became readily apparent. The thoughtfulness and profundity of his wisdom on these matters surfaced during their talk, his level of understanding on these matters effectively outshining that of his religious counterpart. Clearly there was much more going on in the mind of this artist than just figuring out how to apply pigment to canvas.

As for the source of Vincent’s troubles, it’s uncertain exactly what caused them. There are numerous suggestions that he suffered from some form of mental illness. It’s also been said that he drank too much and didn’t take proper care of his health. Or perhaps he was one of those visionaries who was ahead of his time and simply didn’t have the means to put his thoughts and ideas into an understandable form of expression. Whatever the cause, though, he found it perpetually frustrating to come up with an answer that suitably satisfied his hunger to create in ways that defined his outlook and sufficiently incorporated the breadth of his vision.

Painter Paul Gauguin (Oscar Isaac, left), a colleague of Dutch artist Vincent van Gogh, offers friendship and guidance to his misunderstood peer in the new historical character study, “At Eternity’s Gate.” Photo by Lily Gavin, courtesy of CBS Pictures.

Accomplishing such a task can be a tall order. We may very well lack the insights to connect the dots associated with this, or we may be deficient in our conscious wherewithal to sufficiently carry out this mission. That’s where it certainly helps to have an awareness of, and proficiency in, the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains we manifest the reality we experience through the power of our thoughts, beliefs and intents in conjunction with our divine collaborator. Van Gogh almost certainly never heard of this concept, but, based on what he struggled to understand, he obviously had a familiarity with its rudiments; he merely lacked the means to fully grasp or describe it. However, based on the works he created, he was obviously on the path to figuring it out, and, in doing so, he let his paintings do the talking for him.

To his credit, van Gogh clearly knew that there was a connection between what we create and the divine source that provides inspiration and makes the materialized outcome possible. And, because divine capabilities are so much more extensive than what most of us are able to envision, even capturing fleeting glimpses of the range of such possibilities can be overwhelming. Putting an awareness of this into words is like trying to express the nature of being in a sentence of 10 words or less, and the more one tries to do so, the more frustrating it can become, especially if we become obsessed at attempting it.

This would appear to have been van Gogh’s plight – he simply lacked the definition in his beliefs to ably express the limitless possibilities he intrinsically understood in a much more limited, finite context, no matter how creative he was. And it drove him mad. The feelings of “inadequacy” that he must have felt under such circumstances had to have been debilitating and eminently disappointing. It’s as if he was on the precipice of understanding everything but couldn’t sufficiently encapsulate its meaning. But, then, given the magnitude of what he was attempting to deal with, that was an inherently impossible task, at least to accomplish through conventional means.

After a bout of madness that resulted in him severing his ear, painter Vincent van Gogh (Willem Dafoe) seeks to find peace of mind through his art in “At Eternity’s Gate.” Photo by Lily Gavin, courtesy of CBS Pictures.

To compensate for such matters, one could attempt to overcome them by formulating different and more all-encompassing beliefs. But, again, given the scale of what van Gogh was trying to express, even this would likely be insufficient. So, given the challenge of a task like this, what is one to do? That’s where finding a new means of expression – and formulating the beliefs capable of supporting it – comes into play. And, for Vincent, that’s where his paintings took center stage.

It’s unfortunate that van Gogh’s art wasn’t appreciated by his contemporaries. However, those who create works on the cutting edge are seldom understood or taken seriously during their own lifetimes. Their creations are typically meant for generations yet unborn, for those who are subsequently able to look past conventional thinking and embrace a broader vision. In such instances, the creators of these pieces may no longer be around, but their works are, and, at such a time, these masterpieces can thus do what they were intended to accomplish in the first place – expand our collective outlook and urge us to think about art and existence in ways that our forerunners were incapable of envisioning or appreciating.

In that sense, van Gogh devised the beliefs and means to make such an outcome possible. For instance, he painted quickly, a skill that proved invaluable to someone who wanted to produce a prolific body of work during an unusually short life-span. He may not have consciously been aware of his early demise, but on some level he may have sensed the need for urgency in getting his work done during the time frame that he had available.

The speed and immediacy with which Vincent painted also suggests an innate understanding of the importance of creating in the moment, the only time over which we have any meaningful control over what we manifest. Capturing the essence of our beliefs in such fleeting instances is crucial to do them justice, something we mustn’t squander if we want our creations to authentically embody what we think, believe and feel about them in such a transitory time frame. Again, on some level, van Gogh grasped this and imbued himself with the skills necessary to make this possible.

Those who have ever been on the verge of breakthrough insights but have not been able to fully grasp or express their meanings can probably appreciate, at least approximately, what van Gogh went through. This film shows what it means to possess a special wisdom that struggles to be birthed into existence, one that’s difficult to put into words (or any other art form for that matter). The frustration in this can be exasperating, but, then, maybe the knowledge that’s meant to be imparted in these situations isn’t supposed to be chronicled in conventional terms. Perhaps van Gogh had trouble explaining himself and his vision through words because it wasn’t meant to be portrayed through that medium, that it was supposed to come through the paintings he created instead. Maybe he couldn’t appreciate this notion for himself, even though he could envision the finished products through which such wisdom was meant to be given life. Either way, we should be grateful for the gift of enduring beauty that he left us.

Despite some artistic self-indulgence, the inclusion of some sequences that feel unnecessarily padded and occasionally inexplicable choppy editing, this beautifully filmed paean from director Julian Schnabel is a fitting homage to the artistic genius. The filmmaker’s latest doesn’t follow the typical film biography format but, instead, examines the thoughts, beliefs and outlooks of the artist as depicted through the most significant events during the last years of his life, incidents based on van Gogh’s own writings and those of people who knew him. This exploration of the creative process as seen through the eyes of someone overwhelmed by its infinite and divinely inspired possibilities is a moving and thoughtful work that transcends the mere mechanics associated with the craft of painting (or any other art form for that matter). Dafoe gives a masterful, award-worthy performance as the tormented painter, effectively bringing to life the brilliance (and the madness) of this immensely talented, and immensely misunderstood, soul. It’s a portrayal that has already earned him a Golden Globe Award nomination for best actor in a drama, one of many that are sure to come. “At Eternity’s Gate” certainly isn’t for everyone, but, for those who appreciate cinema that attempts to push boundaries and get below the surface of someone’s worldly persona, this offering does as fine a job as any in seeking to fulfill these goals.

The brush strokes we lay down on our personal canvases, whether or not such an act actually involves painting, provide us with an opportunity to give heartfelt expression to our respective creative visions. While it would be ideal that we understand what they mean, sometimes we can’t fully grasp them or the intent behind them. Perhaps, as van Gogh speculated, such creations aren’t meant for those of one’s time, that they’re intended for a future generation and that our role is to merely serve as the messenger for bringing them into being. What’s most important, though, is that we follow through on our mission, for what we manifest may have implications whose impact extends far beyond us and our stay on the planet. That was certainly true of van Gogh, and we should forever be grateful for the gifts he has given to the world.

Copyright © 2018, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

Leave A Comment