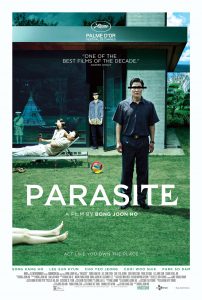

‘Parasite’ exposes the fallout of false intentions

“Parasite” (“Gisaengchung”) (2019). Cast: Kang-ho Song, Hye-jin Jang, So-dam Park, Woo-sik Choi, Sun-kyun Lee, Yeo-jeong Jo, Jung Ziso, Hyun-jun Jong, Jeong-eun Lee, Myeong-hoon Park, Seo-joon Park, Keun-rok Park. Director: Bong Joon-ho. Screenplay: Jin Won Hon and Bong Joon-ho. Web site. Trailer.

When the have-nots stare down the ample resources of the haves, there’s almost always sure to be a degree of envy involved. “How is it that they’ve come to acquire what we haven’t?” they might legitimately ask. “Why can’t we have some of that?” Those questions have merit, too. But how far are the have-nots willing to go to get what they seek? That’s a crucial issue posed in the new social satire, “Parasite” (“Gisaengchung”).

Times are tough for the Kim family. With money and work hard to come by, the foursome struggles to survive in their cramped, rundown apartment. Family matriarch Chung-sook (Hye-jin Jang) seeks to earn money folding pizza boxes, a job at which she’s not especially suited, while her husband, Ki-taek (Kang-ho Song), a jack of all trades, will take anything he can get. Their son, Ki-woo (Woo-sik Choi), a former military man, can’t seem to find a position that matches his skills, while his sister, Ki-jung (So-dam Park), an adept graphic artist and computer operator, languishes without a job. Things look bleak.

The Kim family (from left), son Ki-woo (Woo-sik Choi), father Ki-taek (Kang-ho Song), mother Chung-sook (Hye-jin Jang) and daughter Ki-jung (So-dam Park), struggle to eke out a living in an economically disparate society in director Bong Joon-ho’s masterful new release, “Parasite” (“Gisaengchung”). Photo courtesy of NEON CJ Entertainment.

However, when Ki-woo’s friend Min (Seo-joon Park) pays him a visit, a new door opens. Min, a college student who’s planning to embark on a year of overseas study, works as a private English tutor for a wealthy family, a job that pays quite generously. He tells Ki-woo that he’s recommending him to take over in his absence, an offer that his unemployed friend finds tempting but puzzling. Ki-woo doesn’t believe he’s qualified for the job, but Min reminds him of how well he scored on college admissions tests and that he could readily take over for him. Min explains that his teenage pupil, Park Da-hye (Jung Ziso), is the daughter of an affluent businessman, Park Dong-ik (Sun-kyun Lee), and a stay-at-home mother, Park Yeon-kyo (Yeo-jeong Jo). Min adds that Da-hye’s mom is rather dim and gullible, someone who could be easily bluffed into hiring Ki-woo as his would-be successor.

Though skeptical, Ki-woo agrees to an interview, during which he discovers that Min’s description of his prospective employer is right on target. He tactfully schmoozes Yeon-kyo, who’s quite impressed with Ki-woo’s alleged pedigree. His hopes and enthusiasm are further raised when he meets his student, to whom he takes quite a shine, an attraction that’s apparently mutual. It looks like the job is his.

During his visit to the Park family residence, a lavish home built by and once inhabited by a famous architect, Ki-woo also meets the family’s young son, Da-song (Hyun-jun Jong), an intelligent but hyperactive youngster with a penchant for creating colorful but bizarre works of art. Yeon-kyo boasts her pride in her son’s accomplishments but says she wishes she could find someone who could help guide him in his efforts, a statement that gives Ki-woo an idea: He says he knows a skilled art instructor who could provide Da-song with helpful coaching, someone with whom he could put in a good word. Yeon-kyo jumps at the chance, unaware that Ki-woo is talking about his sister, a relationship he doesn’t reveal.

Wealthy businessman Park Dong-ik (Sun-kyun Lee, left) and his gullible stay-at-home wife, Park Yeon-kyo (Yeo-jeong Jo, right), get duped into unwittingly hiring an entire family of employees with dubious plans in mind in the hilarious new social satire, “Parasite” (“Gisaengchung”). Photo courtesy of NEON CJ Entertainment.

In no time, Ki-jung is working as an “art therapist” for Da-song, a position on which she sells Yeon-kyo after convincingly pointing out the recurring “troubled” imagery in her son’s artwork. And, thanks to a referral from Ki-jung, Ki-taek soon becomes the Parks’ new family chauffeur after the crafty art therapist sets up the disgraced now-former driver (Keun-rok Park) into being fired based on trumped-up allegations. Something similar occurs when Ki-taek manipulates the dismissal of the family’s long-time housekeeper, Moon-gwang (Jeong-eun Lee), creating an opportunity for a glowingly recommended Chung-sook to fill the now-vacant caretaker position.

Given this good fortune, one would think the Kims would be grateful for their newfound prosperity. However, having gotten a taste of the good life, they look for new ways to feather their nest even further – and by even more nefarious means. And, when the Parks go away for a camping weekend to celebrate Da-song’s birthday, the Kims move in to their employer’s home to party down, unapologetically availing themselves of the comforts of affluence. They enjoy ample food and drink and celebrate their unforeseen luck.

But the festivities take an unexpected turn when a late night visitor – Moon-gwang – appears on the doorstep, claiming she’s come by to collect something that she left behind in her hurried departure after her unforeseen termination. By giving the former housekeeper access to the house, the Kims set off a series of events that will change everything. It’s a situation further complicated by the Parks’ unexpected early return from their weekend getaway. Suddenly, all of the Kims’ gains are on the line, an ominous development that doesn’t bode well for the future as things go from great to disastrous in short order. Now what?

Economically oppressed siblings Ki-jung (So-dam Park, left) and Ki-woo (Woo-sik Choi, right) hatch a scheme to become employed by a wealthy family, a plan fraught with unforeseen consequences, in “Parasite” (“Gisaengchung”). Photo courtesy of NEON CJ Entertainment.

When seeking to improve one’s lot in life, is it acceptable to do whatever it takes – even if it means resorting to underhanded tactics? In all likelihood, the answer would depend on who one asks – and what their circumstances are. Those responses – and the outcomes they’re intended to engender – depend on one’s beliefs. And those beliefs, in turn, play an important role in what manifests, thanks to the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains we draw upon the power of those metaphysical building blocks in realizing the reality we experience. However, given that our beliefs faithfully materialize what we’re thinking and feeling, we had better be careful what we ask for, as the characters in “Parasite” find out for themselves.

The Kims, for example, believe that life has shafted them and that they’re perfectly entitled to, and justified in, pursuing whatever it takes to make up for lost ground. What starts out as a mostly genuine employment opportunity quickly transforms into a scam, one that pays off handsomely but that also is rife with pitfalls waiting in the wings. But, given the family’s history of desperation, they’re willing to take the chance to get the result that they believe they’re owed.

Similarly, the Parks are also anxious to get what they want, and they’re willing to do what it takes to obtain the desired result, even if they aren’t as diligent as they could be in investigating their prospective employees. In fact, as members of the affluent class, they probably feel good about themselves in offering employment to those in need, that their “generosity” makes up for whatever economic disparities set them apart from the working class that is otherwise unable to share in society’s good fortunes. Because of this perceived magnanimity, they’re able to sleep comfortably at night, even if they’re unaware that their actions have unwittingly contributed to the problems that caused such fiscal inequality in the first place.

Affluent but clueless housewife Park Yeon-kyo (Yeo-jeong Jo) sets up her family for unexpected fallout when she hires a scheming band of domestic employees in director Bong Joon-ho’s “Parasite” (“Gisaengchung”). Photo courtesy of NEON CJ Entertainment.

In both of these instances, the families engage in the practice of un-conscious creation or creation by default. The Kims and the Parks each do whatever it takes to get their desired outcomes, regardless of the consequences or the impact on others. This approach to the manifestation process can indeed be a perilous one, because focusing on the result at all costs can lead to all manner of unanticipated – and undesired – side effects. This is particularly true where individuals prey on one another – like parasites – to attain what they want. It’s truly a path fraught with potential trouble – and disastrous endings.

A chief reason why this course is so problematic is that it lacks a fundamental component of effective belief formation and subsequent manifestation – integrity. By failing to be truthful with ourselves, our beliefs become “tainted” by considerations that can derail or thwart what we claim we seek to create. The Kims, for instance, say they’re looking for gainful employment, but all the while they’re secretly plotting to find ways to rip off their employers and acquire other perks. Given the deception involved, is it any surprise, then, that things can go awry? A little integrity could go a long way toward staving off problems, but such a result would depend on integrating it into the belief formation process from the outset, something a parasite is unlikely to do, as seen here.

This powerful cautionary tale serves up an important warning to anyone seeking to use the conscious creation process to improve his or her lot in life. It may be tempting to take short cuts, fudge matters or compromise our principles when convenient, especially if doing so gets us the results we want quicker, more easily or in greater measure. But we could also be playing with fire if we do so, even when we feel justified, potentially leaving us even worse off than when we started, and what would that get us?

Dissecting the struggle between the classes through the lens of human nature and personal motivations – regardless of class status – provides the foundation for this rip-roaring dark comedy, one of those rare films that grabs your attention and holds it from start to finish without letting go. Building on themes explored in such previous works as “Snowpiercer” (2013), writer-director Bong Joon-ho presents a riveting, ruthless offering that undeniably makes its point but without being heavy-handed or cartoonishly over the top. In doing so, the filmmaker dishes out a wealth of utterly hilarious humor about subjects that ultimately prove to be no laughing matter. Easily one of the year’s best, especially in its razor-sharp writing, the fine performances of its excellent ensemble cast and a thought-provoking message that should give us all a lot to think about, this superb release never disappoints and consistently satisfies.

“Parasite” is already generating considerable awards season buzz, a tremendous accomplishment for a foreign language film. Having deservedly captured Palme d’Or honors at this year’s Cannes Film Festival, the event’s top prize, the picture is amassing ample clout as an Oscar contender in multiple categories, including best film, again, a remarkable coup for a foreign language offering. The picture is playing surprisingly widely on domestic movie screens, and it’s pulling down bigger-than-normal box office numbers for a non-US release. But, then, given the well-deserved accolades “Parasite” is garnering, those accomplishments are genuinely merited.

It’s unfortunate that we live in a world where so many unfairly go without. One would think that the fortunate would be more willing to share their abundance with those in need. What’s more, it’s understandable that the destitute would take drastic measures to preserve and protect themselves. However, when the downtrodden begin resorting to means like those used against them to obtain what they want, are they any better off in the end? One could say that they are themselves no different from the parasites who have oppressed them. And we all know what ultimately happens to parasites in the end.

Copyright © 2019, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

Leave A Comment