‘1917’ shows us the reality of reality

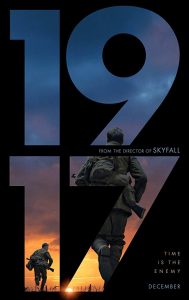

“1917” (2019). Cast: George MacKay, Dean-Charles Chapman, Colin Firth, Benedict Cumberbatch, Mark Strong, Andrew Scott, Richard Madden, Daniel Mays, Claire Duburcq, Roland Maaser. Director: Sam Mendes. Screenplay: Sam Mendes and Krysty Wilson-Cairns. Web site. Trailer.

How aware are we of our existence? We may think we have a good handle on it, but do we really? Sometimes we need a “reality check,” where we’re thrown into a scenario that gives us a greater and more mindful appreciation of the realm in which we find ourselves. That can be a rude awakening, for sure, as a pair of young soldiers discover for themselves in the new wartime drama, “1917.”

With the brutal combat of World War I stuck in a virtual stalemate between opposing British and German forces on the ravaged French landscape, it appeared as though the woefully deadlocked battle would rage on in perpetuity unless some kind of significant break in the impasse occurred. Yet, as unlikely as that possibility began to seem, in April 1917, it looked as though just such a development was starting to emerge. German troops began what appeared to be a retreat, leading British forces to believe that their enemy was at last on the run, opening up an opportunity for an assault that would give them the upper hand. There was just one problem with that assessment: British military intelligence learned that the alleged German retreat was a ruse to trap the advancing British soldiers, leaving front-line forces vulnerable, for all practical purposes, to a battlefield massacre. And, since the German troops cut the communications lines in their withdrawal, there was no way to warn Allied forces of what they were up against.

To prevent a disaster, British Gen. Erinmore (Colin Firth) commissioned two of his soldiers, Lance Cpl. William Schofield (George MacKay) and Lance Cpl. Thomas Blake (Dean-Charles Chapman), to traverse the battle-scarred countryside to deliver a warning to Col. Mackenzie (Benedict Cumberbatch), commander of the front-line troops. The young recruits were thus charged with embarking on a dangerous journey to be carried out on a tight time frame. And, with the lives of 1,600 British soldiers at stake, including the older brother of one of the messengers, Lt. Joseph Blake (Richard Madden), success was absolutely crucial.

Under harrowing conditions, the two young soldiers thus begin their arduous journey. Along the way, they encounter all manner of battlefield horrors, including countless unburied decaying corpses, packs of enormous ravenous rodents, booby-trapped bunkers and relentless enemy snipers. They also witness disasters, such as a tragic biplane crash and a village set ablaze whose burning buildings resemble the gates of hell. To be sure, there are allies to be had, too, such as a convoy of British troops led by wise and compassionate Capt. Smith (Mark Strong), who offers profoundly insightful advice about delivering the warning if the messengers indeed succeed in their task. But, even with such assistance, the journey is a race against time – and tragedy – to prevent an even greater calamity from happening.

Lance Cpl. William Schofield (George MacKay, center) desperately seeks to deliver a warning to the commander of British troops being set up for a trap by German forces in the compelling new World War I drama, “1917.” Photo by François Duhamel, courtesy of Universal Pictures and DreamWorks Pictures.

“1917” is an intriguing film in a number of ways, both in terms of its face value messages, as well as its deeper, metaphysical meaning, qualities conveyed both by the picture’s narrative and its approach in telling that story. Both are accomplished by a common root, the beliefs that made it all possible, both in the minds of the characters in the script and in the imagination of the filmmakers. And, in each case, these accomplishments are attained thanks to the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains we draw upon these powerful metaphysical tools in manifesting the reality experienced both in the lives of the characters on the screen and in the minds of audience members viewing their story as it plays out.

One of the key themes in this picture is its depiction of the hell of warfare, and drawing upon World War I to do that is an intriguing choice. Given that it was essentially the first modern conflict, it represented the first time that new types of weapons capable of inflicting horrific damage were used. In many ways, it wasn’t clear just how destructive they could be until they were actually deployed, and this war provided that opportunity. It showed us, for better or worse, just how deadly and devastating they could be, something that began to open eyes about where the practice of warfare could be headed. Instead of being celebrated as a grand adventure for young, impressionable, naïve youth, war was, likely for the first time, beginning to be seen as the atrocity it is. And this film, while graphic but not gratuitous, depicts that for viewers, particularly those who may have gone into the theater believing otherwise.

Lance Cpl. William Schofield (George MacKay, right) and Lance Cpl. Thomas Blake (Dean-Charles Chapman, left) cross battle-ravaged France to deliver a message to their fellow British troops in director Sam Mendes’s latest offering, “1917.” Photo by François Duhamel, courtesy of Universal Pictures and DreamWorks Pictures.

This is by no means meant to denigrate the heroism of the courageous soldiers who went off to war to fight what they believed was a noble cause. The efforts of the brave young corporals to relay their message under harrowing circumstances is by all means something to be saluted, even if the film’s larger message is designed to get us to question the wisdom of how we end up getting ourselves into situations where we need to tackle tasks like this in the first place. From the characters’ perspective, we get to see their beliefs laid out before them in the reality they experience, offering them glimpses of the nobility they cling to, as well as the sheer terror that accompanies this scenario. And, from a filmmaker’s perspective, given this complex and contradictory mixture of influences involved here, seamlessly blending them into a single narrative requires striking a delicate balance that shows the validity of each set of beliefs and what they ended up manifesting.

Which is where the creator’s astutely insightful storytelling techniques for this tale come into play. Director Sam Mendes, with the collaboration of legendary cinematographer Roger Deakins, filmed “1917” as if it were one long, continuous shot. By filming the picture in this way, the audience is with the protagonists for the entire movie, always by their side, as if viewers were vicariously part of the narrative. In fact, the only way one can realistically get away from the story would be to get up and leave the theater.

British Gen. Erinmore (Colin Firth, center) commissions two of his troops to deliver a warning to his front-line troops being set up for a trap by German forces in the compelling new World War I drama, “1917.” Photo by François Duhamel, courtesy of Universal Pictures and DreamWorks Pictures.

By shooting the film in this way, Mendes gives viewers a front-row seat to the action, an in-your-face way of letting the audience in on the perils that the protagonists face. It’s a technique that effectively enhances the themes of heroism and horror that the picture conveys to those watching it. In many regards, it makes the story seem more “real” than if it were told using more conventional filming techniques, making the experience more “personal” for the viewer, something that I believe is critical to depicting exactly what constitutes the wartime experience – and makes us think twice about why we would consciously create circumstances consisting of such conditions in the first place.

On an even more metaphysically fundamental level, “1917” not only drives home the reality of the wartime experience, but it also makes reality in general seem more “real” than movies or other visual media produced with more traditional practices. On a philosophically instructional level, that makes this a truly important film, one that clearly depicts “the reality of reality.” In an age where it’s easy for us to tune out and lose touch with what’s going on around us, “1917” helps to increase our awareness of the existence that surrounds us, intrinsically connecting us and making apparent what role we play within it. That’s quite an accomplishment for a film that superficially would seem to be just telling us a war story, a quality that really allows it to make its mark in the world of cinema.

Lance Cpl. William Schofield (George MacKay) enters a French town set ablaze by allegedly retreating German troops, creating a scene resembling the gates of hell, in the compelling new World War I drama, “1917.” Photo courtesy of Universal Pictures and DreamWorks Pictures.

Despite a somewhat slow beginning, this otherwise-gripping tale somewhat reminiscent of “Gallipoli” (1981) takes viewers on a first-person journey through battle-ravaged Europe. By bringing the war to the front row of the theater, audiences get to experience the terror of the conflict through a story capable of genuinely frightening viewers better than any of the best horror flicks on the market. The fine lead performances of MacKay and Chapman, along with Deakins’s stunning photography, Thomas Newman’s riveting score and Mendes’s expert direction, combine to make this truly one of the year’s best offerings. The effect may leave viewers feeling a bit claustrophobic and shell-shocked at times, but then that’s a sure sign the filmmakers have done their job.

“1917” has been lavishly praised in this year’s awards competitions. The National Board of Review named it one of 2019’s Top 10 films and bestowed a special achievement award to Deakins for outstanding cinematography. At the Golden Globes, the film won awards for best dramatic picture and best director, along with a nomination for best score. In the Critics Choice Award contest, “1917” took home honors for best director (tied with Bong Joon Ho for “Parasite”), cinematography and editing, as well as five additional nominations, including best picture. In upcoming competitions, the film has earned nine nominations in the BAFTA Awards, including best picture and director, and 10 Oscar nods, including best picture, director and original screenplay. That’s quite a haul for a truly impressive picture.

Getting a warning to British Col. Mackenzie (Benedict Cumberbatch, right) in time to prevent a battlefield massacre is the assignment given to Lance Cpl. William Schofield (George MacKay, left) in the highly decorated World War I drama, “1917.” Photo by François Duhamel, courtesy of Universal Pictures and DreamWorks Pictures.

In an age where we find our senses being increasingly dulled by all sorts of distractions, it can be easy to lose track of what constitutes our reality. It’s a practice we engage in at our peril, for, if we lose sight of our existence, we may eventually lose sight of ourselves, wandering about lost in a reality where we have no connection to our surroundings, how they arose or how we got there. Films like “1917” help to shake us out of that complacency, waking us up to what’s going on and forcing us to become aware of how we respond to it. Ideally, it would probably be better to not have to be pushed into such circumstances, but, just in case we need a potent reminder, we have examples such as this to wake us up – and to keep us from drifting off into scenarios we’d much rather avoid.

Copyright © 2020, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

Leave A Comment