‘Les Misérables’ asks us to examine our intentions

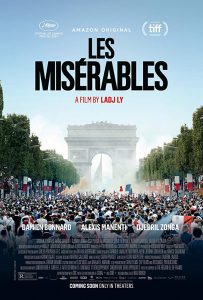

“Les Misérables” (2019). Cast: Damien Bonnard, Alexis Manenti, Djebril Zonga, Issa Perica, Al-Hassan Ly, Steve Tientcheu, Almamy Kanoute, Nizar Ben Fatma, Raymond Lopez, Jeanne Balibar, Fodjé Sissoko. Director: Ladj Ly. Screenplay: Ladj Ly, Giordano Gederlini and Alexis Manenti. Book: Victor Hugo, Les Misérables. Web site. Trailer.

Many of us often look upon the world and wonder why it exists in the state that it does. Some elements seem so patently unfair and incapable of being made better. What’s more, the task of rectifying them is so daunting that it appears to be an impossible undertaking, one clearly beyond our abilities. However, if we make the effort to scrutinize the underlying cause of these conditions, it might not be so difficult to do after all. But that, of course, all depends on us, a message at the core of a modern-day remake of a literary classic, “Les Misérables.”

In the mid-19th Century, legendary French author Victor Hugo (1802-1885) was witness to some of the most turbulent times in his nation’s history, particularly in matters of humanitarianism and social justice. His observations of the circumstances and conditions of the period, especially in the lives of the poor in communities like Montfermeil on the outskirts of Paris, often provided inspiration for his writings, most notably his magnum opus on the subject, Les Misérables, first published in 1862. In that five-volume work, he chronicled the difficulties afflicting the French underclass and their struggles for reform, drawing attention to a subject that had long been ignored and that many in society and officialdom did not want to address. But Hugo’s best-seller struck a chord and pushed French society to begin looking at what it would rather not see.

In the years since then, one would like to believe that we’ve made progress at overcoming those past indignities. However, from the viewpoint of modern-day Montfermeil residents, one might be tempted to remark – trite though it may be – that the more things change, the more they stay the same. That’s especially true for those who live in les Bousquets, high-rise public housing projects that are home to poor, mostly Muslim immigrants from former French colonies in Africa. Even though these residents may look and live differently from those who occupied Montfermeil in Hugo’s time, they face many of the same hardships, and their lives might easily be chronicled in accounts not all that different from what the iconic author wrote.

That, in essence, is what this film seeks to impart. Other than a smattering of passing allusions to its source material, the story in this version of “Les Misérables” has little to do with bread-stealing protagonist Jean Valjean and his arch antagonist Inspector Javert (and even less to do with the popular musical adaptation of their decades-long saga). Instead, director Ladj Ly’s offering features a contemporary drama that elaborates upon the humanitarian and social justice themes covered in Hugo’s novel to illustrate how present-day conditions mirror those that the author wrote about. It shows how the downtrodden of today face challenges not unlike those that confronted by their predecessors, that les misérables of the 21st Century may not be all that different from les misérables of the 19th Century and that the title of their story is just as germane to them as it was to their forbears.

In many regards, “Les Misérables” could be characterized as a contemporary crime drama. When recently divorced police detective Stéphane Ruiz (Damien Bonnard) relocates to Paris from rural France to be closer to his son, he takes a job as a beat cop responsible for helping to keep the peace (as much as that’s possible) in the Montfermeil community, a rundown, crime-ridden immigrant neighborhood. It’s a side of Paris many don’t see, one that’s not pictured in travel brochures, yet it nevertheless needs monitoring by authorities to keep matters from getting out of hand.

Ruiz, a mild-mannered, stand-up sort, is not alone in his work. As part of a trio that patrols the streets, he’s joined by Gwada (Djebril Zonga), a Black, easygoing officer who grew up in the neighborhood, and Chris (Alexis Manenti), a White, hot-headed, strong-armed control freak who leads the group and proudly relishes his nickname “Pink Pig.” Together they seek to keep order, frequently employing questionable practices (generally initiated under Chris’s direction) and paying regular visits to street allies, such as Le Maire (“the Mayor”) of Montfermeil (Steve Tientcheu), the head of the community’s criminal underworld who helps keep a lid on neighborhood violence while handsomely lining his own pockets. It’s all somewhat unsavory in Ruiz’s mind, but he goes along with the routine as much as he’s able to, often clashing with Chris in the process.

Newly arrived police recruit, Stéphane Ruiz (Damien Bonnard, left), starts his first day on patrol of the Montfermeil neighborhood of Paris with his colleagues, group leader “Pink Pig” Chris (Alexis Manenti, center) and patrolman Gwada (Djebril Zonga, right), in director Ladj Ly’s Oscar-nominated feature, “Les Misérables.” Photo courtesy of Amazon Studios.

The relative “calm” in the neighborhood becomes upset, however, when Zorro (Raymond Lopez), the gypsy owner of a small travelling circus, angrily complains to Le Maire that someone from his community stole his beloved lion cub, demanding the animal’s return under the threat of a repeat visit the next day “with guns blazing.” The Mayor claims to know nothing about the lion’s disappearance and calls in his police associates to help sort out the situation.

Chris, Gwada and Ruiz agree to help Le Maire in the search for the missing animal, an investigation that leads to strained relations between the Mayor and others in the neighborhood, most notably Salah (Almamy Kanoute), an influential and devout business owner with a strong local following. But, thanks to Ruiz’s soothing mediation skills, tensions ease somewhat. And, with some astute police work, the officers quickly find the lion cub in the possession of Issa (Issa Perica), a teenage troublemaker with a long history of run-ins with authorities. However, retrieving the cub is easier said than done; when Issa flees, he’s joined by other local teens who run interference for him, thwarting the officers’ attempts at capturing the perpetrator. In the crush of the moment, the mob creates havoc that results in the firing of a flash-ball weapon, injuring the suspect. And, to complicate matters further, the entire incident is captured on video by an overhead drone operated by a shy, geeky teen, Buzz (Al-Hassan Ly), who becomes the subject of a new investigation – one aimed at seizing the device to prevent footage of the incident from being revealed to the public.

The combination of a seriously injured, unpredictable teenage perpetrator, documented footage of the incident in which he was hurt, the desperate search for the owner of the drone that captured images of the volatile event, and an attempt at a deliberate police cover-up make for a highly combustible mix. Add to that the strained relations between Le Maire and neighborhood residents, and the heat gets turned up even further. It all makes for an explosive situation, one that threatens to erupt and create even greater chaos, an episode with the potential to reaffirm everything that Victor Hugo presciently wrote about nearly two centuries earlier.

Le Maire (“the Mayor”) (Steve Tientcheu), head of the criminal underworld in the Montfermeil neighborhood of Paris, seeks to keep a lid on community violence while lining his own pockets in the Oscar-nominated feature, “Les Misérables.” Photo courtesy of Amazon Studios.

The similarity of life in Montfermeil in 2019 compared to the 19th Century raises some interesting – and puzzling – questions. For all of our supposed compassion, tolerance and advanced knowledge, how is it that these kinds of conditions persist? Why do people continue to suffer? Why do we cling to different standards of acceptance – and hence exhibit different standards of behavior – toward different groups of individuals in such areas as justice, opportunities for economic and social advancement, and humanitarian treatment? And, despite changes in the material nature of our world, why have we remained stuck in our outlooks when it comes to how we treat others and how we interrelate with them? Indeed, did we learn nothing from Hugo’s writings?

If we have a hard time fathoming how such conditions have endured during all that time, then maybe it’s time we take a good hard look at ourselves. And, in particular, maybe we should pay special attention to our beliefs, for they provide the building blocks of the reality around us, the cornerstones of the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains we draw upon them in manifesting the existence we experience. These tremendously powerful intangible elements spring forth from within us to materialize our external reality. And, for better or worse, what we get faithfully mirrors the source from which it originates, persisting for as long as such notions continue to receive the power we give to them.

If we consider that, then, it speaks volumes about those questions raised above. If the present-day conditions mimic those of the past with little meaningful change, then we’ve obviously allowed the underlying beliefs that created them to endure. Whether we’ve played an active part in their preservation (as Chris, Le Maire and Issa do, for example) or merely stood on the sidelines as onlookers (as, say, Gwada does), many of us have had a hand in maintaining them with little, if any, change. The power and persistence of these beliefs, in turn, make it difficult for those who hope to see improvement (as evidenced by the frustration Ruiz experiences). In the end, if any of us really hope to see progress made, we have to start with our beliefs, rewriting them as needed to bring about the kinds of adjustments we seek.

This is not to suggest that change is impossible. The power that we give to our beliefs is essentially a neutral force, neither good nor bad; it all depends on what we do with it through the “applications” to which it is put. As Hugo wrote in Les Misérables, “There are no such things as bad plants or bad men. There are only bad cultivators,” and this is just as true where our beliefs are concerned. The same energy that goes into creating something nefarious or injurious could just as easily be applied to the manifestation of something beneficial or joyful. Consider, for instance, the film’s opening sequence in which the residents of Montfermeil join in the jubilation of their fellow Parisians at the Arc de Triomphe to revel in France’s victory at the World Cup soccer championship, a celebration born out of a wellspring of upbeat intentions. By contrast, however, the energy applied so readily to that undertaking could just as well be infused into the criminal activities that those same individuals engage in when they return to their home neighborhood. The question, of course, is, “What will they choose to do?”

The restless and discontented youth of les Bousquets, the rundown public housing projects of the Montfermeil neighborhood on the outskirts of Paris, face a difficult and frustrating upbringing in director Ladj Ly’s gripping new retelling of the classic Victor Hugo novel, “Les Misérables.” Photo courtesy of Amazon Studios.

This is where paying attention to the nature and content of our beliefs comes into play. And, for those who may lack the insight to know how to proceed at this, that is where the impact of beneficial role models can make all the difference. If the Montfermeil residents had more people like Ruiz than like Chris or Le Maire in their lives, they might very well make different choices regarding their beliefs – and, consequently, experience a very different reality from what they’re accustomed to. And, if there were enough Ruizes in the life of the community, then maybe the kinds of reforms Hugo pushed for might finally begin to be realized in greater numbers. But, no matter what unfolds, it all comes back to the beliefs that are put into place to begin with.

It should be noted that, as in Hugo’s age, Montfermeil is far from an isolated example in our world today. There are many communities like it around the globe where conditions are as bad as, if not worse, than there. The violent events in this film, not unlike the 2005 Paris riots on which portions of this picture were inspired, should serve as a wake-up call, not only to change the conditions, but also to change the underlying beliefs that have brought these conditions into play in the first place. “Les Misérables” is a good starting point to draw from, providing us with a powerful cautionary tale we should all take to heart.

This stunning urban crime drama adaptation provides a gritty, contemporary twist on the notions of liberty, equality, fraternity and social justice (and their all-too-frequent absence) all these many years later. Director Ladj Ly’s Oscar-nominated offering for best foreign language film, influenced strongly by Spike Lee’s “Do the Right Thing” (1989), hits hard, seldom holding anything back. With its fine performances, excellent cinematography and compelling electronic soundtrack by Pink Noise, the film captivates as it works its way through an increasingly tense narrative that leaves as many questions open as it resolves. This version of “Les Misérables” may not superficially resemble any of those that preceded it, but it leaves an impact just as emotionally powerful – if not more so – than any of its predecessors, bringing Hugo’s message into the present and shoving it squarely in our faces.

Paris erupts in jubilation at the nation’s victory in the World Cup soccer championship, a rare moment of joy in “Les Misérables,” a contemporary adaptation of the classic Victor Hugo novel about the challenges faced by the downtrodden in French society. Photo courtesy of Amazon Studios.

Were it not for the existence of Bong Joon Ho’s masterpiece “Parasite” (“Gisaengchung”), “Les Misérables” might otherwise be the best foreign language film of 2019, a distinction that likely would have made it possible to sweep all the honors in this category in the movie industry’s various awards competitions. As it is, the picture earned the Jury Prize at the Cannes Film Festival and was a nominee for the Palme d’Or, the event’s highest honor. Since then, however, in addition to its Oscar nod, the film has consistently pulled down nominations in the Golden Globe, Critics Choice and Independent Spirit Award contests, accolades of which it is certainly deserving and, in another year, might have easily translated into victories. But, even without a trophy case full of hardware, this is a picture well worth its weight in praise and definitely worth seeing.

Bringing fairness and justice into the world is something mankind has sought to do throughout its history, with varying degrees of success. Some can argue that we have indeed made progress, and they can point to a number of noteworthy examples. But, as long as certain basic inequalities are allowed to endure, we’ll never live up to the promise and potential of what we might be able to achieve as a species. We can only hope that Victor Hugo’s message sinks in at some point – and that we truly become what we’re genuinely capable of.

Copyright © 2020, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

Leave A Comment