‘Clemency’ pushes us to look at our personal morality

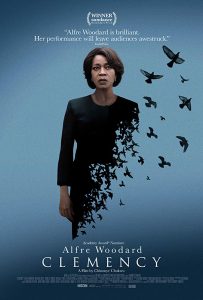

“Clemency” (2019). Cast: Alfre Woodard, Aldis Hodge, Wendell Pierce, Richard Schiff, Richard Gunn, Michael O’Neill, Vernee Watson, Dennis Haskins, LaMonica Garrett, Danielle Brooks, Michelle C. Bonilla, Alex Castillo, Alma Martinez. Director: Chinonye Chukwu. Screenplay: Chinonye Chukwu. Web site. Trailer.

Life and death matters generally give us pause to reflect upon our outlook on life, especially from a moral standpoint. But what happens when we’re conflicted? Can we sort out our feelings to come up with beliefs that lead to the right decisions about such issues? Such is the dilemma faced by a high-ranking prison official in the intense new drama, “Clemency.”

Bernadine Williams (Alfre Woodard) has spent many years as the warden of a maximum security prison, and, from the way she’d probably describe herself, she’s done a damned good job at it, too. Her no-nonsense, by-the-book demeanor governs all of her actions, and she diligently maintains her steely, unflinching façade at all times. That’s true even in moments of high tension, such as the many executions of death row inmates that she has overseen. Always the professional, she never lets emotions get in the way of doing her job.

But all the years of doing this work have slowly taken their toll. As button-down and in charge as Bernadine appears outwardly, she’s beginning to show signs of wear internally. She drinks too much. She has trouble sleeping. She’s quick to dig in her heels when challenged, especially by attorneys seeking to advocate on their clients’ behalf and even by the families of inmates politely petitioning for special requests. But, most of all, she has difficulty getting close to people, including her loving husband, Jonathan (Wendell Pierce), who’s beginning to have serious doubts about the future viability of their marriage. In fact, the only people with whom she seems to have any kind of meaningful relationships are her co-workers, particularly Deputy Warden Thomas Morgan (Richard Gunn) and, somewhat ironically, Chaplain David Kendricks (Michael O’Neill). It’s as if she’s an island unto herself, and the tide is ever rising.

Prison warden Bernadine Williams (Alfred Woodard) oversees executions of death row inmates as part of her job, one that grows increasingly difficult for her, in the tense new drama, “Clemency.” Photo by Eric Branco, courtesy of Neon.

The heat gets turned up further when two volatile incidents occur. The first is an execution gone terribly wrong when the staff responsible for carrying out the procedure is unable to find a suitable blood vessel to insert the IV line used for administering the lethal medications into the convict (Alex Castillo). As he writhes in pain, he begins to experience what might readily be called cruel and unusual punishment, a terrifying sight that clearly flusters the usually unshakable Bernadine as she seeks to follow through on her duty and maintain as much order as possible.

In the wake of that troubling event, Bernadine is quietly shaken, especially when she begins getting pressured for answers from the press and death penalty opponents. For perhaps the first time ever, she’s less certain about herself, her responsibilities and her willingness to proceed in her capacity as warden. That doubt is further fueled by the scheduling of another upcoming execution, one that involves inmate Anthony Woods (Aldis Hodge), who may very well be innocent of the capital crime of which he was convicted. She tries to downplay her feelings, carrying forward in a business-as-usual manner, despite her growing – and increasingly visible – apprehensions. Those feelings become more noticeable to others, too, such as Woods’s attorney, Marty Lumetta (Richard Schiff), who’s increasingly convinced she can’t hide from her feelings – or herself.

How will Bernadine resolve these issues? Can she remain committed to her job and to the practice of capital punishment? Those are the questions she must address, not only from a vocational standpoint, but also when it comes to how she sees herself and what her work may be doing to her soul. In many ways, one could say she’s just as much a prisoner of her circumstances as are the convicts who reside within her prison’s walls.

Circumstances like this force us to come face to face with ourselves and our beliefs. Because of the high-stakes nature involved, we’d be wholly irresponsible to address them flippantly, dismissively or without thoughtful consideration. And the reason for that is that our beliefs play a crucial role in the reality we experience, a product of the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains we draw upon these metaphysical building blocks in manifesting our existence.

When we employ our beliefs to create scenarios as intense as the one presented in this film, we’re treading into potentially dangerous territory. It’s obvious that using conscious creation in such a way is intended to address significant life lessons, the kind that deserve to be treated cautiously, reverently and with all deliberate seriousness given what’s at stake.

These situations give us much to consider. For example, are they something we really want to create? Are we genuinely interested in being (and/or remaining) a part of them? If not, why not? And, if that’s the case, can we find a way to extricate ourselves and change our circumstances? Those are difficult questions, and the answers may not be readily forthcoming – unless we’re willing to take a concerted look at the beliefs that got us into these scenarios and make an effort to change the conditions.

This is clearly what Bernadine is wrestling with in this story. It’s as if she’s painted herself into a corner and doesn’t know how to find her way out of it. She does what she thinks is best to cope with these conditions, but they’re mere bandage solutions based on temporary fixes. To a much greater degree, she’s wrapping herself up in a blanket of denial, refusing to squarely face the beliefs that got her into these circumstances in the first place. And, because of that, she’s effectively trapped, unable to avert her attention away from matters that she can no longer bear to look at. That’s the epitome of being a prisoner of one’s own beliefs.

If Bernadine hopes to escape her situation, she must be willing to look at her beliefs honestly, with a resolute sense of integrity. Why is she doing this kind of work in the first place? Why has she stayed with it so long? And why does she seem to have so much trouble tearing herself away from it? Until she’s able to answer these kinds of questions, she’ll be unable to come up with solutions that help to solve her dilemma.

Even if Bernadine is able to address the foregoing issues, she still needs to ask herself if she’s willing and capable of making changes. Can she envision alternatives that take her away from the self-created hell in which she finds herself? And, if so, does she have any idea what such a new reality might look like? That may be a challenging venture for her, given how long and how deeply she’s been ensconced in her present circumstances. Dragging herself out of those conditions could be more than she’s prepared to handle.

Of course, it’s always possible to do so with help. Bernadine certainly has sources of assistance available to her if she chooses to avail herself of them. First there’s her husband, Jonathan, who genuinely expresses his concern on multiple occasions. Then there are her professional peers, Chaplain Kendricks and Deputy Warden Morgan, both of whom clearly care about her well-being and seem willing to step in when needed. Even attorney Lumetta appears to have some quiet compassion for the warden, despite the many times in which they butted heads. If Bernadine were to reach out to any of these resources, she’d find she has helping hands upon which to draw, but she must decide – and believe – that this assistance would be in her best interests.

The consequences involved here are incalculably high, particularly where Bernadine’s personal welfare is concerned. If she were to turn a blind eye to her innermost beliefs, she faces the possibility of killing someone who’s not ready to die, as well as putting an innocent man to death in error. Can she live with this? Or would she be better off by walking away and beginning a new life, one in which she didn’t have such heavy responsibility on her shoulders and in which she could allow her true self to at last emerge? The choice is hers, and her beliefs will activate the events and circumstances that arise from those choices. We can only hope that she’ll choose wisely given the potential karmic consequences that await her and her mortal soul.

Capital punishment issues are frequently the stuff of robust social discourse, but how often is it scrutinized at the personal level? That’s what this intense new drama seeks to do, both for the executioner and those awaiting that ultimate fate. How does it feel to be the individual on death row? And how does it feel to be the one who orders that the final act be sanctioned? The moral dilemmas faced by all involved may not be as easy or clear-cut to decipher as one might think. Woodard gives a superb (and criminally overlooked) performance, enhanced by the picture’s chilling cinematography and excellent supporting cast. Admittedly, the film could have used more development of the protagonist’s motivations and back story, as well as a slightly brisker pace overall. However, these shortcomings aside, this one is likely to haunt viewers after leaving the theater, giving us all much to think about when it comes to matters of justice, life and death. For its efforts, “Clemency” has picked up three Independent Spirit Award nominations for best feature and screenplay, as well as Woodard’s lead performance.

If we’re not truthful with ourselves when it comes to the kinds of matters examined in this film, there may be hell to pay, be it figurative or perhaps even literal (depending on one’s beliefs). This is why it’s so crucial to get it “right” where these issues are involved. If we don’t, a lasting legacy could dog us for a long time, preventing us from finding peace – and launching us onto a path that might make us long for a resolution that, sadly, ever eludes us.

Copyright © 2020, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

Leave A Comment