‘Spider’ spins a troubling web of truth

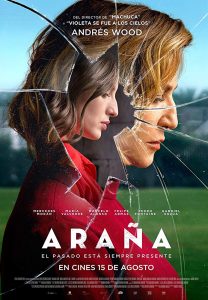

“Spider” (“Araña”) (2019). Cast: María Valverde, Mercedes Morán, Gabriel Urzúa, Felipe Armas, Pedro Fontaine, Marcelo Alonso, María Gracia Omegna, Mario Horton. Director: Andrés Wood. Screenplay: Guillermo Calderón. Web site. Trailer.

Truth can be a powerful weapon, one that can both avenge wrongs and operate as a force of devastating destruction, sometimes simultaneously. The power associated with it can have tremendous ramifications and in a variety of contexts. And, when evidence of truth in both its aspects surfaces, the implications can be staggering. So it is for three individuals whose stories are rooted in the past and thought forgotten until they’re unexpectedly revived in the present, an intense saga depicted in the taut Chilean political thriller, “Spider” (“Araña”).

In 1970, socialist Salvador Allende (1908-1973) became president of Chile, the first Marxist ever democratically elected to a nation’s top office in Latin America, an outcome widely greeted with much popular fanfare. However, not everyone was pleased with the result, most notably right-wing conservatives who opposed the new president’s proposed reforms, some of which included the nationalization of certain industries. Those who stood to lose from such changes organized formal opposition groups, most notably the radical Fatherland and Liberty Nationalist Party. The organization’s aggressive and sometimes-brutal tactics included everything from assaulting leftists in street brawls to formally planning Allende’s ouster (a result that eventually came to pass in a 1973 coup). The FLNP also became somewhat infamous for its distinctive logo, a series of interlocked lines meant to represent the chains of Marxism arranged in a pattern that resembled a spider (as depicted in the accompanying photos).

The FLNP’s membership primarily consisted of upper and middle class college students, and the story in this film follows the exploits of three of them – Inés (María Valverde) and her boyfriend, Justo (Gabriel Urzúa), both of whom recruit a soft-spoken but violent-tempered peer, Gerardo (Pedro Fontaine). The trio is something of an unlikely threesome: Inés, a beauty pageant contestant, and Justo, a product of the Chilean bourgeoisie, are significantly different from Gerardo, a military veteran from a working class background. It’s not clear how solidly Inés and Justo are committed to the cause, but Gerardo is all in, providing their cell with much-needed muscle when called for. Nevertheless, despite their differences, they work together to carry out the organization’s missions and spread its rhetoric.

Chilean college students Inés (María Valverde, left) and her boyfriend, Justo (Gabriel Urzúa, right), become active proponents of the right-wing conservative Fatherland and Liberty Nationalist Party in the early 1970s, seeking the ouster of the nation’s democratically elected Marxist president, Salvador Allende, as depicted in director Andrés Wood’s latest offering, “Spider” (“Araña”). Photo courtesy of Film Factory.

However, matters grow complicated when Inés starts taking a liking to Gerardo. The passion that swells up between them quickly turns hot and heavy, and their less-than-discreet interactions eventually raise Justo’s suspicions. Consequently, when Justo assigns hazardous tasks to his new recruit, one can’t help but wonder if he’s doing so because he believes Gerardo is the best man for the job or because the dangers involved in these tasks could potentially take him out of the picture – and out of the life of Inés. That notion gets put to the test when the assignment involves a proposed political assassination, an ideal task for a former military man – and one in which having a potential patsy in place could prove valuable to protecting the movement and fulfilling its objectives.

Skip ahead to the present day. An older Inés (Mercedes Morán) is now an influential and successful businesswoman active in Chilean commerce and politics. She’s married to Justo (Felipe Armas), but time has not been kind to him; he’s an alcoholic shadow of his former self, largely withdrawn and much less in the public eye. Their affluence supports them comfortably, but the secret of their FLNP past forever haunts them, threatening to wipe away their prosperity and destroy the illusion of their so-called respectability if the truth were exposed.

The potential for undoing everything gets amped up with the return of their old colleague, Gerardo (Marcelo Alonso). After a disappearance of more than four decades and believed dead, he returns to Santiago, looking very much like a dissheveled hermit. He’s apparently still committed to taking down those he considers “undesirables,” though he’s not pursuing Marxists any more; he has new targets (most notably thugs and immigrants), and he seems set on going after them.

As Gerardo cruises the streets of Santiago’s seedier neighborhoods, he looks on in anguish. He’s disgusted by the seemingly omnipresent criminal element, surveying the landscape like a vigilante in waiting, a latter-day version of Travis Bickle from “Taxi Driver” (1976). And, when he witnesses a street robbery, he pounces, chasing down the perpetrator and killing the criminal with his car in an act of what he sincerely believes to be a justifiable citizen’s arrest. However, once taken into custody, authorities lock him up, especially when they learn that he has a huge stockpile of weapons stashed away.

Violent-tempered military veteran Gerardo (Pedro Fontaine, left) is recuited to provide muscle for the right-wing conservative Fatherland and Liberty Nationalist Party in 1970s Chile by college student Inés (María Valverde, right), a relationship that turns romantic as well as political, in director Andrés Wood’s new thriller, “Spider” (“Araña”). Photo courtesy of Film Factory.

When Inés learns of his arrest, she grows concerned and seeks to call in favors to safeguard her security by keeping him in confinement. But, even with that, many questions linger: Why has Gerardo returned? Will he reveal details about his past that will also implicate Inés and Justo? Is he securely detained, unable to escape his incarceration? And what would happen if he somehow managed to get out? Many potential consequences hang in the balance, including Inés’s criminal history, as well as her current reputation, her personal safety and those 40-year-old unresolved romantic leanings.

As the past and present collide, a great deal of long-accumulating dust is about to be stirred up. Truths will be revealed, and the ramifications associated with them will surface in multiple ways. In the end, though, they can’t be escaped – and neither can their implications.

When we’re unable to be truthful about ourselves (or sometimes even with ourselves), we run the risk of spinning a web of deceit, which is why “Spider” is such an aptly fitting title for this film. The protagonists in this story – especially Inés and Justo – have difficulties with this, failings that are apparent both in their past and in their present. In large part, that’s due to their inability to define and understand their authentic selves, an issue that arises from not knowing what to believe about their true nature. And this shortcoming, unfortunately, drives their implementation of the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains we draw upon our beliefs in manifesting the reality we each experience.

For instance, as noted above, when it comes to their commitment to the FLNP, the younger Inés and Justo seem somewhat unclear about exactly why they’re involved. Is it because they truly believe in the right-wing cause? Is it a power and control move? Or is it a byproduct of their backgrounds, protecting the bourgeois lifestyles they grew up with, maintaining the status quo and playing along with their peers for acceptance and popularity? Such personal ambiguity is potentially volatile in light of the risks involved in a scenario like this, something that one should be clear about with oneself before getting in too deep. And this is important not only for them while in their youth, but also down the road in their adulthood, something that their younger selves apparently aren’t thinking much about.

Creating our existence without giving due consideration to the associated consequences can be a time bomb whose detonation can occur at any time, both in the short term and well down the road. And that, for example, is where the danger of recruiting an impressionable Gerardo comes into play. Inés and Justo believe that having a strongman on their team would be advantageous to furthering the FLNP’s actions and objectives, and, from a purely goal-driven standpoint, they’re probably right. However, given Gerardo’s history and behavior, he’s obviously loose cannon, one who can be easily influenced and manipulated, especially when he’s called upon to execute the kinds of high-risk party initiatives that align with his particular point of view. By failing to evaluate the wisdom of their actions and beliefs, Inés and Justo are potentially lighting a fuse that could have explosive outcomes associated with it.

An elder Inés (Mercedes Morán), a modern-day successful businesswoman, seeks to keep her radical past under wraps in the new political thriller, “Spider” (“Araña”). Photo courtesy of Film Factory.

Efforts like this are prime examples of un-conscious creation at work, a skewed version of the philosophy whereby desired outcomes are given priority over any potential side effects or fallout that may occur. The roots of this approach are firmly planted in the pasts of the three protagonists, but that doesn’t mean that their misguided schemes will go dormant or evaporate over time. As the seeds germinate, they can come to life as full-blown manifestations, and, for the lead trio in this story, that can have wide-ranging impact on multiple fronts. For Chilean society at large, for example, the efforts and effects of the FLNP can be seen both during its days of active operation and years in the future, results made possible through the overt and covert power amassed by onetime members like Inés and, despite his long absence, Gerardo. Meanwhile, on a personal level, similar ramifications can be seen in the lives of the three former colleagues, most notably their unresolved romantic issues. Indeed, even when we would like to believe that such matters are over and done with, nothing could be further from the truth (there’s that word again).

Under conditions like this, one must often scramble to address undesired outcomes when they arise. The elder Inés, for example, must aggressively call in favors to protect her reputation and personal well-being when she learns that Gerardo may have walked back into her life. Similarly, the elder Justo attempts to deal with his past, both politically and romantically, by escaping into a perpetually inebriated existence to deaden the pain and keep denial at bay. And Gerardo, who no longer has familiar targets to pursue, must come up with new ones to stalk and hunt down to satisfy the drives that have become so ingrained in his beliefs and in the reality he seeks to manifest.

In many regards, “Spider” is an important film for all of us these days, for it holds up an undeniable and sparklingly clear mirror, forcing us to take a good look at who we are as a people, perhaps even as a species. It shows us the power of our beliefs in creating what unfolds in our existence, especially with respect to the persistence of those notions over time. Old beliefs, including those that no longer serve us, have a tendency to hold on, making their presence felt in both big and small ways even when we thought they had become outmoded and had been discarded. Yet there they are, their effects lingering like uninvited party guests who won’t leave, compelling us to take action to address them.

At first glance, one might think that the foregoing is a uniquely American phenomenon, especially in light of recent events. However, as this film illustrates, it’s more widespread than many of us might believe. Indeed, as director Andrés Wood observed during a question-and-answer session after a screening at the Chicago Film Festival, such happenings are occurring outside our borders, even if we hear little to nothing about them, and the intents underlying them have uncanny commonalities linking them. Because of that, then, “Spider” serves as a wake-up call to us, both individually and collectively and around the world, not just in terms of the tangible effects of these considerations, but also with regard to the underlying intangible means that bring them into being in the first place. The truth will out, so, if we want to better understand why it’s materializing as it is, we had better get to know what’s driving it in the first place.

Unfortunately, even though “Spider” is such an important film, finding it may be a bit difficult. It has primarily been playing the film festival circuit, but its general distribution future is unclear. If viewers wish to see this offering, they should push for a general release. The effort would be well worth it. Director Wood delivers an engaging, edge-of-your-seat thriller with a message that’s just as important today as it was in the past, told through a series of flashbacks seamlessly woven into the present-day narrative. The romantic story line doesn’t work quite as well as its political and social counterpart, but the picture’s excellent performances, editing and pacing make this offering a cinematic knock-out, another excellent example of the works coming out of one of the world’s foremost emerging film industries.

Try as we might to keep our secrets from surfacing, they almost assuredly will at some point, and their revelation could expose some painful truths. So we’d be wise to consider the ramifications up front before buying into notions whose consequences we’re unprepared to handle. Like a spider who spins its web, we do the same with the reality we create. But we had better be careful how we do so to avoid being caught in our own trap.

Copyright © 2019-20, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

Leave A Comment