‘Divine Love’ questions the nature of authentic faith

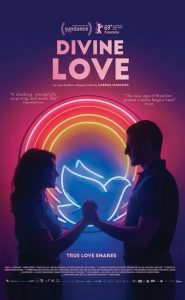

“Divine Love” (“Divino Amor”) (2019 production, 2020 release). Cast: Dira Paes, Julio Machado, Antonio Pastich, Teca Pereira, Emílio de Melo, Clayton Mariano, Mariana Nunes, Suzy Lopes, Thardelly Lima, Thalita Carauta, Tuna Dwek, Thiago Justino, Edilson Silva, Nataly Rocha, Calum Rio (narrator). Director: Gabriel Mascaro. Screenplay: Gabriel Mascaro, Richard Daisy Ellis, Esdras Bezzerra, Lucas Paraizo and Marcelo Gomes. Web site. Trailer.

For many of us, faith is looked upon as central to our worldview and existence. Its form may vary somewhat from individual to individual, but its essence is generally the same. However, no matter how much we may proclaim we adhere to our faith, how authentic are we with ourselves when it comes to our practices matching our contentions in this regard? Do we cling to our faith with absolute fidelity, or do we try bending the rules when necessary to suit other agendas? And what happens if our faith is tested and we’re reluctant to acknowledge the manifestation of an aspect of it with which we disagree, despite supposed claims to the contrary? Those are among the questions raised in the new Brazilian religious satire, “Divine Love” (“Divino Amor”).

In a Brazil of the near future in which fundamentalist Christianity has insidiously ingratiated itself into what is still a supposedly secular state, elements of the church and its ideology have intrusively invaded virtually every aspect of everyday life. Evidence is everywhere, too, such as in the opening of ecclesiastical discos and drive-through pastoral advice centers. This development has thus come to affect the rights of everyone, including non-believing “infidels.”

This is apparent, for example, in a government registry office, where Joana (Dira Paes), a notary in charge of marriage and divorce records, manages to incorporate her devoutly pious views into seemingly every client consultation she conducts, especially with individuals and couples seeking to separate from their spouses or one another. Joana has taken it upon herself to act like an impromptu marriage counselor, couching the legal details of their impending separations in advice about what they can do to reconcile their differences and save their relationships. Her unsolicited gesture is met with mixed results, and, while Joana’s supervisor (Antonio Pastich) doesn’t particularly condone this practice, he also does little to squelch it. Because religious fundamentalism has become so ingrained in society – even in official functions – its practitioners are given considerable leeway by those in power to operate as they see fit, despite public claims that the country and its government remain free of such faith-based influences.

Brazilian notary Joana (Dira Paes, left) augments her client consultations with unsolicited fundamentalist Christian teachings with mixed results in the biting new religious satire, “Divine Love” (“Divino Amor”), now available for online streaming. Photo courtesy of Outsider Pictures.

Despite occasional objections, Joana nevertheless feels compelled to keep up her efforts, to enthusiastically share her devotion with others. She’s particularly thrilled when she finds those who are receptive to her brand of evangelizing, especially if such guidance helps set individuals and couples on the path to preserving their marriages. For those who express interest, Joana encourages them to join her and her husband, Danilo (Julio Machado), at gatherings of an organization known as Divine Love. The purpose of the group is for loving couples to get together to share their faith, particularly as it relates to their relationships, expressing how their devotion to Jesus has strengthened their marriages.

But there’s more to Divine Love than just reading scripture and sharing personal stories. Because many of the couples who attend the organization’s sessions are in marriages that are teetering on the brink of failure, one of the aims of the group is to look for ways to bring the partners back together, particularly when it comes to once again spicing up the romance between them. And that’s where Divine Love’s little secret comes into play – by encouraging struggling couples to engage in uninhibited sexual escapades, both with one another and other couples. The thinking (though some might say rationalization) behind this is that, by freeing ourselves from the erotic inhibitions that prevent our unrestrained divine love from flowing through us to our partners (even if liberated with the “assistance” of others), we can restore our sacred devotion to our spouses and our commitment to our relationships. Lovemaking of any kind with both partners and others is fair game with one exception – men are only allowed to climax with their spouses. After all, if that restriction weren’t in place, Divine Love contends, it would violate God’s sacred will.

Joana and Danilo appear to enjoy their involvement with Divine Love (some might legitimately say, “with a ‘morally sanctioned’ arrangement like that, who wouldn’t?”). They get the satisfaction of helping others while maintaining the strength of their own relationship. In fact, they generally seem fairly happy with one another except in one area: They dearly want to have children, but, no matter how much they try, they continually fail. Danilo tries a variety of techniques and technologies to increase his sexual viability. And Joana prays constantly, asking God for assistance when she’s not visiting the drive-through pastoral advice center to consult the resident cleric (Emílio de Melo). But nothing seems to work – that is, until one day.

With her husband Danilo (Julio Machado, right), fundamentalist Christian Joana (Dira Paes, left) revels in joys of a faith-based marriage support group with a twist in director Gabriel Mascaro’s latest offering, “Divine Love” (“Divino Amor”). Photo courtesy of Outsider Pictures.

While passing through a special scanner that provides read-outs on various aspects of one’s health and personal well-being, Joana learns she’s pregnant. She’s overjoyed, giving thanks that God has finally answered her prayers. However, when she looks into the paternity of the child, she discovers that it’s not attributable to Danilo – or to any of the other men from Divine Love who could have inadvertently inseminated her. After ruling out all of the possible fathers, she’s left with only one conclusion – she’s carrying a child who possesses a genuinely divine heritage. Indeed, God answered her prayers alright, but certainly not as expected.

Joana sees this blessed event as a miracle. But will everyone see it the same way? Will others share her joy in the revelation that she’s carrying the child of God, the second coming of Jesus that Christians have awaited for so long? Or will they see her as a blasphemer, one who dares to claim that she’s an integral part of a sacred prophecy not to be treated so sacrilegiously? And what of Danilo and her Divine Love family – how will they react, with support or scorn? The question of genuine faith is thus put to the test. One can’t help but wonder, however, how will it fare?

Many of us would contend that faith, like patience, is a virtue, something we strive to attain, though with varying degrees of success. In this regard, much depends on our degree of truthfulness with ourselves: How honest are we being when it comes to what we’re seeking and the elements that constitute it? Are we truly seeking to achieve what we claim to be pursuing? Or are we placing qualifiers on our ultimate goal, ancillary (or even seemingly unrelated) elements that could compromise or distort the authenticity of what we say we ultimately want?

Group retreats are among the distinctive rituals practiced by an uninhibited fundamentalist Christian marriage support group in “Divine Love” (“Divino Amor”). Photo courtesy of Outsider Pictures.

That’s where our beliefs come into play, for they shape the nature of our objective and the means we employ in reaching it. And those intents, in turn, will be reflected in the reality we experience, the core principle underlying the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains we draw upon these metaphysical resources in manifesting our surrounding existence. But how exactly does this happen?

Our beliefs, in essence, are mirrored in what unfolds, and the outcome will “faithfully” (no pun intended) depict that input. What’s more, the stronger our convictions – that is, the more “faith” we place in them – the more authentic the results we’ll achieve. But it’s also important to remember that faith itself is a creation, and how well we manifest it will depend on what we put into it.

For many of us, this most obviously comes into play where religious and spiritual beliefs are concerned. The faith we have in these areas will thus be apparent in the materializations associated with these aspects of our lives. If we subscribe to a particular doctrine, the degree to which our reality reflects it will depend on the degree we adhere to its particular principles and concepts. If we are firm believers who sincerely place our heartfelt faith in its precepts, the more our existence will embody those attributes.

But what happens if we try to “fudge” our convictions? Suppose we’re only willing to embrace a doctrine’s principles up to a certain point. In a case like this, it would follow that our faith would be reflected only up to that point in our resulting reality. For instance, if the fundamentalists in this story claim to firmly believe in a second coming of Jesus but then question the possibility when someone like Joana contends that it’s about to happen, can those doubters legitimately have an authentic faith in their doctrines if they fail to follow through on their convictions when the opportunity presents itself?

When fundamentalist Christian Joana (Dira Paes, left) needs a shot of inspiration, she visits one of Brazil’s drive-through pastoral advice centers to consult the resident cleric (Emílio de Melo, right) in the biting new satire, “Divine Love” (“Divino Amor”). Photo courtesy of Outsider Pictures.

When circumstances like this arise, a door can open to an array of unexpected consequences. Disillusionment, despondency and disappointment, for example, are all possible. Likewise, the entire belief structure associated with that doctrine – that is, our faith in it – could potentially fall apart like a house of cards. Then where would we be?

If someone were to doubt Joana’s claim of being a modern-day Virgin Mary, for example, she might be made to feel like a pariah, even though deep down inside she may genuinely believe that she’s fulfilling a divine prophecy, one very much in line with the tenets of religious doctrine and her own faith. At the same time, those who doubt her contention might be quick to label her a blasphemer, an objection that might seem to call their faith into question, prompting onlookers to ask, “Do they really believe what they claim to believe?” In both instances, the faith and beliefs that had been in place could collapse, leaving their adherents without anchors in their religious and spiritual lives. Then what?

What’s perhaps even more troubling, however, are scenarios in which we try to place qualifiers on what we claim to believe and what’s integral to the nature of our faith. This raises the specter of hypocrisy emerging. For example, are Divine Love’s principles about rationalized spouse swapping really in line with Christian teachings about marriage and fidelity? Or are they being justified into existence to support its followers’ desire to get freaky outside the bounds of their primary relationships, all supposedly in the name of their religious doctrines? Granted, there’s arguably nothing inherently wrong with wanting to have a robust sex life with multiple partners, but at least be honest about it – that it’s an end in itself that’s being sought, not one that’s being pursued in the name of Jesus, especially since it’s not generally seen as being part and parcel of Christian teachings.

An ongoing inability to have children is a source of strain in the otherwise-happy marriage of Joana (Dira Paes, left) and her husband, Danilo (Julio Machado, right), in director Gabriel Mascaro’s “Divine Love” (“Divino Amor”). Photo courtesy of Outsider Pictures.

This aspect of the story is particularly telling in light of the ubiquitous sex scandals that have emerged in Brazil and elsewhere in recent decades involving religious leaders and other “authority” figures. One can’t help but ridicule the hypocrisy involved in these situations. If those who claim to speak for Jesus and the divine would only be honest with the public (and themselves) about the nature and extent of their “animal urges,” it’s likely that outsiders (and perhaps even some followers) would cut them a lot more slack about their personal proclivities. Their flocks could still have faith in them for their candor rather than ire for their insincerity. Being spiritual and sexual aren’t mutually exclusive, so why the pretense about their needing to be – or the trumped-up justifications for trying to make them seem religiously compatible?

There’s also a real danger when such mindsets seep out of their religious contexts and into other areas of life, as this film so clearly illustrates. That’s apparent, for example, in Joana’s workplace evangelizing. When religion and government become intertwined, it represents a potentially volatile mix, such as when Joana tries to “counsel” an uninterested client (Thalita Carauta) on a secular matter from a spiritual perspective. As Joana attempts to force her views on someone who’s indifferent to her proselytizing, the situation heats up, opening it up to unpleasant side effects for all concerned. But, more than that, it sets a hazardous precedent for society at large, threatening the secular sovereignty of a nation’s entire citizenry.

From a conscious creation perspective, it’s important to remember that the manifestation process is, in essence, a partnership between us and our divine collaborator (no matter what name we may call it). Our partner in this process recognizes the nature of our faith and beliefs, regardless of what they may be, and will bring to us exactly what we ask for, even if we don’t acknowledge, understand or appreciate the result for what it is or what prompted its materialization in the first place. So, in light of that, doesn’t it pay to be honest with ourselves and our collaborator to begin with? Doing so should strengthen our faith in one another and in the process we jointly conduct. It would also bring us closer to our authentic intentions and result in outcomes that more closely resemble them. That’s something we can all have faith in.

“Divine Love” is, without a doubt, one of this year’s most unusual releases, pushing the creativity envelope in truly inventive ways but always leaving viewers with much to ponder in the wake of its inherent improbable strangeness. However, as life has clearly shown us of late, unlikely peculiarity such as this has a possibility of coming into being, and, to that end, the picture serves up a powerful cautionary tale. Director Gabriel Mascaro’s wickedly biting satire exposes some of the hidden dangers that can quietly lurk in our society, no matter how humorous, comical or seemingly well-intentioned they may appear. It also calls us on our proclamations of faith and just how genuine they really are, something that could end up being a striking eye-opener for some of us. The film is currently available for online streaming.

As is the case with many of Mascaro’s films, this offering includes a number of protracted and explicit sex sequences, so sensitive viewers should be forewarned. While some might see this as a gratuitous exercise in pushing the boundaries of acceptable on-screen eroticism, Mascaro is one of a number of emerging filmmakers who obviously believe that sexuality needn’t be soft-peddled in its depiction, that realistic imagery doesn’t automatically make such graphic footage pornography. What’s more, its inclusion here is all part of exposing the phony piety that often goes into the rituals, practices and beliefs of all too many hypocritical faith-based movements, organizations whose missions essentially ring hollow and deserve to be revealed as such.

Faith can serve us well, as long as we serve it well, too. That’s important to remember when we’re up against life’s challenges, especially in critical areas like love and our connection to the divine. When we do so, we have an opportunity to experience “divine love” in its most heartfelt and authentic form. And, if we’re really truthful with ourselves, would we want to experience it any other way?

Copyright © 2020, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

Leave A Comment