‘Minari’ charts the quest for a better life

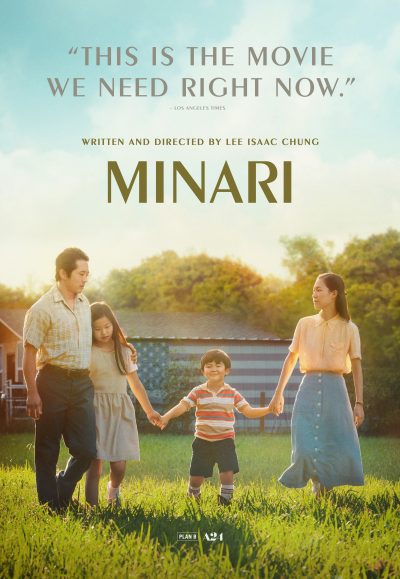

“Minari” (2020 production, 2021 release). Cast: Steven Yeun, Yeri Han, Alan Kim, Noel Kate Cho, Yuh-jung Youn, Will Patton, Ben Hall, Jacob Wade, Darryl Cox, Esther Moon, James Carroll, Eric Starkey, Tina Parker, Jenny Phagen, Scott Haze. Director: Lee Isaac Chung. Screenplay: Lee Isaac Chung. Web site. Trailer.

Wishing for a better tomorrow is one of the most seductive pursuits we can follow. But actually making it happen takes more than just idle pondering. It requires us to envision what we want and to have faith that it can materialize for us. Are we willing to put in the work – both hypothetically and tangibly – to see through on its realization? That’s what a family seeking a better life is faced with in the moving, heartwarming domestic drama, “Minari.”

The American Dream – a life brimming with optimism and opportunity for personal and economic success – is something most of us aspire to, especially those of immigrant backgrounds. And, in the economic boom of the 1980s, it was something that was seemingly on everyone’s mind. So it was for the Yi family, who emigrated to the U.S. from South Korea in search of a better life.

Korean-born Jacob (Steven Yeun) and Monica (Yeri Han) arrived in this country in California, where they spent a number of years working as chicken sexers, separating male and female chicks at a hatchery. While working there, they became the parents of two American-born children, Anne (Noel Kate Cho) and David (Alan Kim), a youngster with a congenital heart problem. They established themselves well, but that existence wasn’t enough for Jacob; he wanted more, to chase the American Dream by making a life for himself and his family as a farmer, something he could not economically afford in high-priced California. So, to make this happen, he pursued another option – to relocate himself and the family to rural Arkansas, home of some of the country’s richest soil and lowest land prices, a place where he could establish his own 50-acre homestead.

The film opens with the family’s arrival in Arkansas. The verdant landscape and big open skies in many ways epitomize the notion of God’s Country. But, despite such a beautiful setting, the transition of moving from California to Arkansas proves to be an uneasy one. While Jacob is truly in his element, Monica struggles to adapt. The idea of living in a mobile home propped up on cinder blocks, for example, is not to her liking, having become more accustomed to an urban existence on the Coast. She’s also concerned about the remoteness of their location, far removed from many of the essentials of life, such as the children’s school and a hospital capable of caring for David’s condition. Adjusting, it seems, is going to be more of a challenge than she thought it would be.

To generate funds to get the farming operation under way, Jacob and Monica draw upon their work experience and take jobs as chicken sexers at a local hatchery. It’s here where the reality of their new community sinks in for Monica; given the dearth of other Koreans, save for Monica’s co-worker Mrs. Oh (Esther Moon), she begins to see how culturally isolated she is. The locals generally appear to be warm and welcoming, but backhanded prejudices slip through occasionally (though, in all fairness, more likely out of ignorance than malice). Nevertheless, these conditions add to the discomfort Mrs. Yi experiences, prompting her to long for the family’s days in California – and making her wonder whether immigrating to the U.S. was a good idea in the first place.

Monica’s anguish soon bubbles to the surface so often that it causes stress in her relationship with Jacob. There’s even talk of her leaving Jacob behind and taking the children to someplace she deems more habitable. But the couple staves off this outcome by coming to a compromise – inviting Monica’s mother, Sounja (Yuh-jung Youn), to come live with them. Having Sounja present would help to provide a cultural cushion for Monica, while giving her someone to help care for the children and affording Anne and David an opportunity to get to know their grandmother better.

Of course, Grandma’s arrival has its share of challenges, too. As much as she adores her grandchildren, Sounja is not exactly the ideal grandmother. She’s got a salty side, and she enjoys her vices, like playing cards and pulling pranks. David isn’t especially thrilled with her presence initially, either, especially when she tries to coerce him into activities like drinking a foul-tasting homemade herbal remedy that she swears will help him with his health condition. In many ways, her arrival is just another log on the fire of adjustment challenges.

As all this unfolds in the household, Jacob keeps his distance by throwing himself into getting the farm up and running. This task takes much of his time and ever-increasing amounts of cash, and it’s a lot of work. Fortunately, Jacob has much-needed help from a farmhand, Paul (Will Patton), a fundamentalist Christian who perpetually praises God and routinely thanks Jacob for the job opportunity. Together this unlikely duo toils to get the fields tilled, planted and watered to produce the Korean vegetables Jacob grows. He hopes that the distinctiveness of his crops will help to distinguish his product with buyers in nearby markets, like Tulsa, where there’s greater demand for more unconventional wares, including those to suit the tastes of the city’s Korean community.

As much hard work as Jacob puts into raising his crops, though, there’s one that grows like a weed with virtually no attention paid to it – a patch of minari planted alongside a nearby shaded creek bed. In fact, the minari patch wasn’t even Jacob’s idea; it was Sounja’s brainchild. When she discovers the site for the planting, she muses about the crop’s ability to proliferate, as well as its many uses as everything from a mood elevator to a healing substance to a culinary ingredient. The parsley-like plant is a sort of agricultural wonder, but it’s one whose value is often overlooked, probably because of its abundant, weed-like growth. Sounja recognizes its benefits, though, even if Jacob doesn’t, so she’s generally left to tend to this planting herself (not that it requires much attention to begin with).

As the family works through its personal and professional challenges – of which more arise as their story plays out – they endure a variety of ordeals, some for the better, some not. The American Dream, it appears, is more elusive than imagined, perhaps even verging more on “the American Myth.” As much as everyone tries to pull together, there are just as many elements that threaten to tear them apart. But, all problems aside, there is always hope and the potential it carries to bring about a suitable resolution. And maybe, if the family sprinkles a little minari on it, that result just might grow.

Embarking on a fresh start can be a daunting prospect. Doing so frequently involves charting new and uncertain territory, much of which we’re likely to have little familiarity. However, that’s often the case when we willingly choose to leave the past behind in favor of something new. And, because of that, we had better prepare ourselves as best we can – not necessarily for the particulars involved in such a venture (though that certainly helps), but at least in terms of being ready for the types of conditions we’re likely to face – challenges, the unexpected, hardships and so forth.

This comes about to a great degree in terms of what we believe, the foundation of the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains we manifest the existence we experience through the power of these intangible metaphysical resources. What we put in place in this regard is crucial, for its outcome draws directly from it, and that’s important when looking to establish a fresh start.

Perhaps the most important aspect in this is envisioning what we hope to achieve, and, from this standpoint, Jacob seems to have a good handle on what he’s looking to create. He may not have anticipated every aspect of his dream, nor may he have envisioned all of the challenges he’d face. But he knows that fulfilling the American Dream is what he’s after. He also has an affinity for the land, something that writer-director Lee Isaac Chung has observed that many Koreans – immigrants or otherwise – share, a trait that naturally draws Jacob to want to become a farmer. So, with those qualities and ambitions in place, Jacob puts the beliefs in place required to see his dream fulfilled. He may not have heard of conscious creation, but it’s apparent he has a good grasp on its concepts and what it takes to make it work for his situation.

Given how Jacob works through his challenges – no matter how daunting they may seem – he obviously has tremendous faith in his beliefs. That’s significant, because faith goes a long way toward cementing us in our beliefs and convictions. And faith is something that seems to come quite naturally to Jacob and his family, as evidenced by their regular church attendance and the place that religion occupies in their lives. It follows that this is something that should also find its way into their beliefs otherwise.

That’s crucial, too, especially when that faith is tested, as it often is during the many challenges they face with adjustment, the farming venture, David’s health and the new living arrangements with Sounja, to name a few. Developments like these may sometimes seem like random, unwanted hardships, but they often show up in our existence as a means to determine our resolve, to get us to see just how badly we want what we claim to seek. New ventures frequently require sacrifice and considerable effort, qualities that often turn out to be commensurate with the rewards that come from them. To appreciate their manifestation, however, we must also often ask ourselves, “Is this really what we want?” In many cases, though, the ordeals generally provide us with the answers. If we truly want the results we profess, we’ll figure out ways to address these considerations – and come up with beliefs to successfully work through them.

In all of these endeavors, we usually obtain the best results when we’re authentic with ourselves. This calls upon us to tap into our sense of personal integrity, no matter what that might involve and how it’s reflected in our manifesting beliefs. Jacob, for instance, exudes authenticity when it comes to his beliefs about what he hopes to achieve. The same can be said for Monica regarding her dissatisfaction with the family’s new living arrangements. And that disconnect between them, as becomes apparent, proves to be a source of heated conflict. It may not be a desirable situation, but at least they’re both being honest with one another, and that’s an essential starting point for them if they ever hope to find a solution that’s going to satisfy everyone. Such authenticity is an integral element for coming up with workable beliefs to arrive at that outcome.

There are, of course, clues as to what’s called for in circumstances like this, and one of Jacob’s crops ironically provides symbolic inspiration. Whether or not the family recognizes it as such, the minari patch, with its prolific yield, serves as an enlightening example. It grows abundantly under the harshest of conditions, and it provides the means to address an array of issues, be they health-related, emotional in nature or culinary. It’s almost as if the plant is eager to help, as if it’s got an innate quality of compassion to serve, to solve problems and to bring about helpful results. It’s almost as if it’s an agricultural metaphor for the love that binds all things, including the members of a family in crisis – people who care about one another and can work together to help each other sort out their problems for the betterment of everyone. And, when viewers see the bumper crop growing in the creekside bed, there’s considerable inspiration that can be drawn from that image – if only the family will allow themselves to see it as well.

This is important for those of us in the viewing audience, too. When we look at our fractured society these days, it’s crucial that we seek ways to heal it if we hope to survive. The squabbles that have come to set us apart – many of them overblown and inherently petty at that – must be resolved, and the healing balm that comes from our own personal versions of minari need to be tapped if we ever hope to realize such an outcome. This film provides us all with an enlightening and inspiring example to follow. Let’s hope we’re paying attention.

Should it be nominated, this is the movie that deserves to win the Oscar for best picture, flat out, hands down, no questions asked. Director Chung’s heartfelt semi-autobiographical drama is just the kind of movie that we need right now (much as “Moonlight” was the film we needed in 2016). The authenticity that pervades the narrative is truly astounding, never presenting a moment that seems forced or out of place. The picture’s exquisite cinematography, nuanced script and narrative, and superb ensemble cast make for a moving cinematic experience that leaves viewers with a warm glow that lasts long after the movie’s final frame. Richly deserving of the many accolades and award nominations it has received thus far, “Minari” truly stands out among this year’s field of contenders, masterfully and lovingly handled in virtually every respect. I can’t speak highly enough about the quality of this film and its power to affect us, especially when it comes to helping heal an ailing nation. The film is playing in limited theatrical release and is available for online streaming.

“Minari” has received numerous accolades thus far, with more almost certainly to come. The picture was named an American Film Institute Movie of the Year and received a Golden Globe Award for best foreign language film. It also fared well with the National Board of Review, where it was named a Top 10 film and captured awards for best director and supporting actress (Youn), and in the Critics Choice Award competition, in which it was named best foreign language film and received the award for best young actor (Kim), along with eight additional nominations (best picture, ensemble, original screenplay, cinematography, score, director, actor (Yeun) and supporting actress (Youn)). In upcoming competitions, the film has earned three Screen Actors Guild Award nominations (best ensemble, actor (Yeun) and supporting actress (Youn)), six BAFTA Award nods (best foreign language film, supporting actor (Kim), supporting actress (Youn), director, score and casting) and six Independent Spirit Award nominations (best picture, director, screenplay, actor (Yeun) and supporting actress (Youn and Han)).

Having faith in ourselves and each other sometimes calls for considerable effort – so much so, in fact, that it might seem easier to throw in the towel. But, in the end, what would that accomplish, especially if we have goals we wish to achieve, objectives that are nearly always part of attaining that sought-after better tomorrow? That’s when we need to tap into our reserves of resolve. And, for good measure, we just might want to throw in a little minari, too.

For a video clip from “Minari,” click here.

Copyright © 2021, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.