‘Fire in The Mountains’ ignites a feminist manifesto

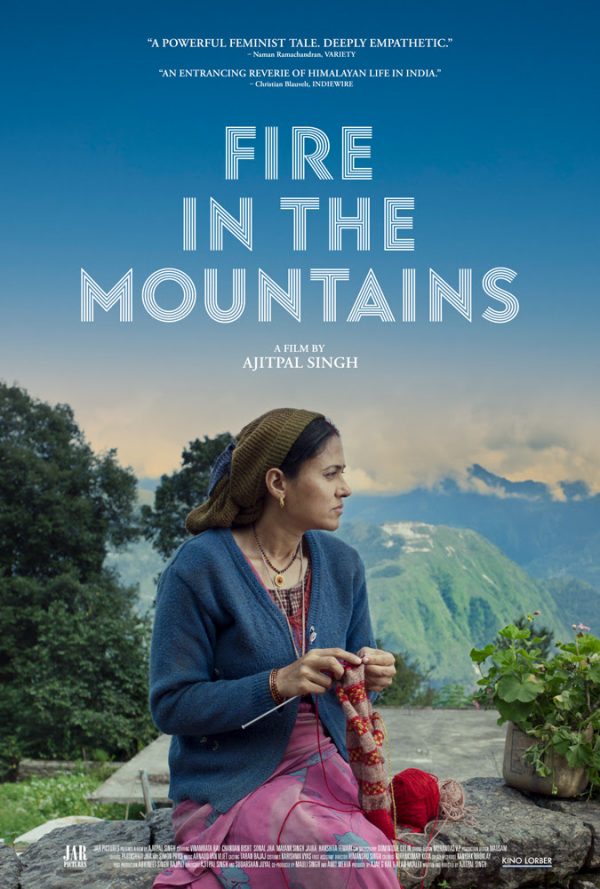

“Fire in The Mountains” (2021 production, 2022 release). Cast: Vinamrata Rai, Chandan Bisht, Harshita Tewari, Mayank Singh Jaira, Sonal Jha, Lalit Pandey, Mukesh Ghasmana, Uma Shanker Madi, Monaj Kumar, Madan Mehra. Director: Ajitpal Singh. Screenplay: Ajitpal Singh. Web site. Trailer.

To paraphrase Bruce Springsteen, it takes a spark to light a fire. But sometimes such blazes don’t take on the first strike, because there’s not enough initial energy behind it to catch flame. In fact, it may take multiple sparks before a conflagration erupts. And it’s a concept that’s applicable both literally and metaphorically. But, when things finally come alive, watch out – a message delivered home with hard-hitting force in the new Indian drama, “Fire in The Mountains.”

India is a land at a cross-roads in terms of embracing modernization while preserving tradition. It’s an often-uneasy mix that struggles to find a suitable balance. And, while one might think that the efforts aimed at modernizing are designed to benefit everybody, not everyone does, especially with the tug of traditionalism fighting against progressive change in certain segments of society, particularly among women.

These conditions are especially prevalent in the nation’s rural areas, such as the State of Uttarakhand in the country’s north, a beautiful region often compared to Switzerland with its scenic Himalayan backdrop. In the village of Munsiyari, a popular tourist spot for adventurous travelers, married couple Chandra (Vinamrata Rai) and Dharam (Chandan Bisht) run a home stay facility for visitors while supplementing their household income from a number of other sources. But, for various reasons, it’s often a difficult, frustrating and volatile way of life.

As the pragmatic voice of the household, Chandra bears the brunt of these conditions. She suffers under the tremendous weight of responsibility for keeping things afloat at home and in the family business, despite Dharam’s constant empty contentions that he’s the one in charge simply by virtue of being a man. She frequently must deal with his abusive alcoholic ways, his irresponsible behavior, and his traditional religious beliefs and practices, many of which she sees as bordering on foolish superstitions. His obsessions with obtaining spiritual dispensations from a local guru (Lalit Pandey) and participating in the traditional Jagar ritual – activities that drain precious funds from the household coffers – leave Chandra scrambling to figure out how to make ends meet, especially paying for the expensive medical care of their physically paralyzed and psychologically withdrawn young son, Prakash (Mayank Singh Jaira).

But these aren’t the only household challenges Chandra faces. She also struggles to deal with her intelligent and self-reliant but flirtatious teenage daughter, Kanchan (Harshita Tewari), who’s smitten with an “eager” neighbor boy, Neeraj (Monaj Kumar). Kanchan possesses a curious mix of personal attributes, some of which are indeed admirable, but others of which are decidedly exasperating – and that only add to Chandra’s burden. Then there’s Kamla (a.k.a. Didi) (Sonal Jha), Chandra’s unappreciative, scheming widowed sister-in-law, who has come to live with the family at Dharam’s invitation. Being that Kamla is Dharam’s sibling, there’s little Chandra can do about the situation except put up with her, something that frequently and seriously tries her patience.

Challenges from outside the household are formidable, too. For quite some time, Chandra and her neighbors have been attempting to get a road built connecting the main highway that runs through their village to their hilltop homes, residences that are otherwise only accessible by a treacherous footpath that’s been etched out of the steep, rough terrain. Chandra has made many appeals to the local village chief (Mukesh Ghasmana) about this project, asking him to take this request to the federal government, which claims to be supportive of such infrastructural improvements in underserved areas. But no matter how often she asks, the proposal falls on deaf ears. The patriarchal attitude and inept, self-serving ways of the chief keep the project from moving forward. And his dismissive, condescending approach to dealing with the “little lady’s” request not only leaves the proposal unaddressed, but is also personally insulting.

Chandra receives the same kind of treatment from Prakash’s doctor (Madan Mehra), as well as from the owner of a competing home stay business (Uma Shanker Madi). However, given the prevailing nature of the local culture, that’s to be expected. It hits Chandra from all directions, including at home and in the outside world. And it constantly places her in a position of having to fight for the fulfillment of her needs, wishes and sometimes even her own personal safety. The feeling of continually being beaten down angers and frustrates her, ever prompting Chandra to have to fight to maintain her sense of personal power.

Moreover, the path to Chandra finding and preserving that sense of personal power is far from clear. Because she’s often on her own in this regard, she has no handbook or role models to draw from. Knowing how to proceed can even be baffling and conflicting at times, such as when this strong-willed woman seeks to rein in her own free-spirited daughter, seemingly squelching the valued sense of independence that one might think she should be proud of Kanchan so courageously and freely exhibiting. But fight on she must, exercising her determination to be herself and to press her case when the need arises.

The result is the emergence of a personal feminist manifesto, one given life in an environment where its leanings have rarely been afforded such free expression. Chandra is serious about seeing those intentions fulfilled, too. In fact, there’s a part of her that’s determined to see that those who have wronged her (and those like her) will have to pay for their transgressions, thereby opening up space for a new society and the creation of a new world. And, in a land like India, with its well-known tradition of the Mother Goddess Kali, whose violent trembling so shook the world that she destroyed it, there’s no telling what might happen if Chandra and her kindreds suddenly decided to comparably let loose their power on an otherwise-unsuspecting world.

Considering how Chandra is routinely treated, her confrontational reactions are entirely understandable. She knows that she deserves better than what she typically receives, and she sincerely believes that attaining such respect is possible, an outcome achievable through the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains our thoughts, beliefs and intents manifest the reality we experience. She may not know exactly how to go about this, and she might not even know of this school of thought’s existence. Yet she appears to have a handle on its basic principles and never hesitates to employ them when needed to pursue what she wants.

However, because this all seems to be new to Chandra, she’s still finding her way through it, which accounts for the variability in the results she realizes. Sometimes, for example, she’s quite adept at manifesting what she needs, such as sufficient cash to cover the most important household expenses despite Dharam’s woeful financial management skills. At other times, though, she meets with less satisfying outcomes, such as her interpersonal dealings with men, including everyone from her husband to Prakash’s doctor to the village chief, all of whom inflict their own forms of abuse on her, ranging from disrespect to outright physical harm. Such mixed results show she still has much to learn, an outcome that can only come with more practice and experience.

So what accounts for Chandra’s uneven performance? As noted above, she still seems to be new at this. And, having been raised in a culture steeped in traditions that still persist, she may likewise have some difficulty getting past the notions she was raised with and subsequently embraced and internalized. This illustrates the power and endurance of our beliefs and how difficult it can be to rid ourselves of them, particularly when we’re not as aware of them as we need to be to rewrite them into more suitable forms. Thus this accounts for what makes this metaphysical undertaking a work in progress for Chandra.

This becomes apparent, for example, in her dealings with Kanchan. Theoretically speaking, Chandra should be proud of the independence that her daughter asserts as it makes for a valuable life skill and serves as a model for what Chandra is trying to achieve for herself. But, when Kanchan seeks to follow her own inclinations, she’s often met with ridicule from her mother – evidence that those old belief tapes are still playing in Chandra’s mind and still emerge when she thinks they’re relevant to the circumstances at hand. This might appear counterproductive to some, but, when persistent outmoded beliefs surface in knee-jerk reactions like this, they can be hard to get past.

In light of this, Kanchan’s presence could be seen as a source of inspiration to nudge Chandra into another way of thinking, one that helps implement the beliefs she needs to put in place to move forward with the fulfillment of her ambitions. The same could even be said for Kamla to a certain extent, even though the example she sets is not exactly the best compared to Kanchan. Nevertheless, in both instances, these influences are in place to help show Chandra that she needs to eliminate what no longer serves her in order for more beneficial beliefs to fall into place. This principle should help Chandra find her way more effectively when it comes to attaining what she seeks to achieve, both in terms of the beliefs she needs to implement and the outcomes that ultimately result.

It’s important to heed such advice, too, for if we willingly or unwittingly fail at this, our goals and the beliefs behind them can become “stuck” inside us. This can lead to them building up to an “unhealthy” level. And, when they finally emerge, they can manifest in an exaggerated, almost fanatical form. When we witness Chandra’s initiatives continually stifled, we can also see the frustration building within her, leading to her attempted manifestations taking on an almost toxic quality. Is that what we really want? Indeed, is that what she really wants? It’s at times like that when we need to look for ways to liberate those stagnant beliefs, not only to attain what we want, but also to prevent them from emerging in ways that could potentially do more harm than good. We all know what kind of fury can be unleashed by a woman scorned, and we’d be wise to do our best to keep such an eventuality from coming to pass.

Director Ajitpal Singh openly avows that his debut feature is based on experiences that he witnessed with relatives who were subjected to the kind of treatment Chandra undergoes. In that sense, then, this is a film intended to make a strong social and personal statement about the unacceptable nature of such circumstances. This picture often packs quite a punch and seldom holds anything back, making for a sometimes-difficult watch (sensitive viewers beware), thanks in large part to the authentically convincing lead performances of Rai and Bisht. Admittedly, some of the narrative’s story threads don’t feel as fully fleshed out as they could have been, making it difficult at times to see exactly how everything connects, no doubt a shortcoming attributable to the film’s scant 84-minute runtime. Nevertheless, for a first-time outing, the filmmaker has laid down an otherwise-impressive and noteworthy cinematic gauntlet, an admirable start to what one can only hope will be a promising movie career. The film is available in a limited theatrical run and for streaming online.

Simmering embers can be ignored for only so long. At some point, they’ll spring to life, spreading over everything in their path and wiping out all that they encounter. And it’s a concept that’s as applicable metaphorically as it is literally. But, either way, when it’s fueled by a massive amount of pent-up energy, the impact can be sweeping. That can yield positive results in the long run but not before putting everything in its way through tremendous turmoil. This thus begs the question, “Which is preferable – a wildfire or a controlled burn?” Choose wisely – the character of the outcome and the quality of the future rest on it.

Copyright © 2022, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.