‘Inversion’ makes the case for fairness, equality

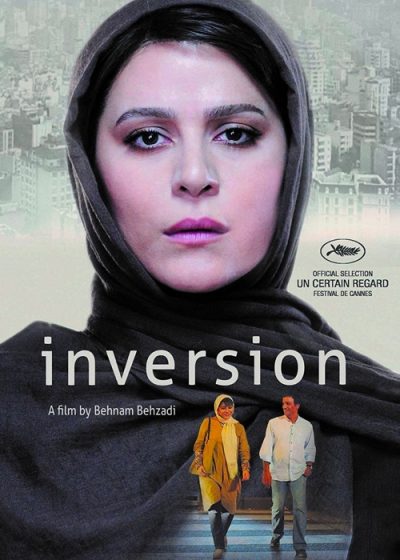

“Inversion” (“Varoonegi”) (2016). Cast: Sahar Dowlatshahi, Ali Mosaffa, Alireza Aghakhani, Setareh Pesyani, Roya Javidnia, Shirin Yazdanbaksh, Setareh Hosseini, Toofan Mehrdadian, Payam Yazdani, Ebad Karimi, Mojitaba Nam Nabat. Director: Behnam Behzadi. Screenplay: Behnam Behzadi. Web site. Trailer.

It goes without saying that we’d all like to be treated fairly and equally. However, no matter how much praise and value we may laud on these concepts, there are countless instances where these principles are compromised or disregarded altogether, leaving some of us out in the cold. And, in the wake of such developments, it’s entirely understandable how those who are slighted come to feel angry, frustrated and desperate, placing them in a position of wanting to lash out for justice. So it is for a young Iranian woman in the 2016 domestic drama, “Inversion” (“Varoonegi”), now available for streaming.

Niloofar Pirasteh (Sahar Dowlatshahi) would seem to have a fairly good life going for her. The responsible, self-reliant, unmarried career woman enjoys what appears to be a fulfilling existence in Tehran, despite the challenges of modern urban living. She runs the tailoring business founded by her late father and, with the aid of her good friend, Soudabeh (Setareh Pesyani). is now looking to expand it with a team of seamstresses. Niloo resides in a small but comfortable apartment with her elderly mother, Mahin (Shirin Yazdanbaksh), a kindly old soul who adores her caring, thoughtful daughter and the attention she provides. She’s also close to her teenage niece, Saba (Setareh Hosseini), who looks up to her auntie as a model of a modern woman. And, on top of all that, quite recently Niloo has begun dating Soheil (Alireza Aghakhani), the owner of a construction business who is the apparent epitome of a perfect gentleman. Who could ask for anything more?

However, before long, circumstances begin to change, and not for the better. Tehran’s infamous smog problem has been exacerbated by hot weather, creating an air quality issue that has curtailed outdoor activities and closed schools. It’s also made for a health crisis that can potentially harm those with respiratory issues, such as Mahin. And, in fact, that’s precisely what happens when she ventures outside without her oxygen, causing her to collapse with difficulty breathing. She’s rushed to the hospital and placed in intensive care, where, fortunately, the staff is able to successfully stabilize her condition.

In the wake of this emergency, Niloo and her family gather at the hospital to check on the patient. In addition to Saba, Niloo is joined by her elder siblings, her brother, Farhad (Ali Mosaffa), and her sister, Homa (Roya Javidnia), along with her brother-in-law, Mojid (Toofan Mehrdadian). They meet with Mahin’s doctor (Payam Yazdani), who says that Tehran’s air quality issue is severely affecting her health and that she should move to a new locale where debilitating smog is not a problem. But where? And who will accompany her to her new out-of-town home, given that she’s not capable of living on her own?

Homa recommends that Mahin should relocate to a vacation home that she and Mojid own in the north of Iran, where the air is cleaner and would be better for the patient’s recovery. Farhad agrees with the idea, and he and Homa decide that Niloo should join Mahin in her new home, a decision they make without asking their sister. They even go so far as to start making financial arrangements for Niloo, considering that she’ll have to give up her business, another decision made on her behalf without her input. But, then, in their view, why should they have to ask for her input? After all, she’s the younger sibling. What’s more, the decision involving Niloo’s forfeiture of her business is seen as benefitting the well-being of the extended family overall, as it will result in the sale of the building in which the tailoring operation is housed, the funds from which Farhad can use to pay off his own delinquent debts. How considerate of – and convenient for – him.

Needless to say, Niloo is not happy with being left out of these decisions. However, in a culture where the men and older siblings are accustomed – even expected – to make decisions for the family, Farhad and Homa figure, why should their younger sister’s opinion matter? But this argument holds no water with Niloo. By relocating, she’ll have to give up her apartment, her business and her budding romance, not to mention the way of life she so readily enjoys in Tehran. What’s more, she’s tired of her family making decisions for her without consultation. It’s become so pervasive in her life that Farhad has even gone so far as to make decisions for Niloo about her own car.

In circumstances like this, Niloo takes comfort in the fact that she can at least count on Soheil to be in her corner. But even that proves to be based on false hope when the allegedly perfect gentleman springs a surprise on her. And, at this point, the only ones who still back her are Saba, Soudabeh and Mahin, but, as emotionally supportive as they all are, there’s little of a practical nature that they can do to help out.

So what is Niloo to do? She decides she’s not willing to roll over and comply with what the others say, especially when they could be doing more to help out, despite their contentions that they have family and financial obligations that keep them from doing so. In response, Niloo offers alternative proposals. She fights back. She even goes so far as to refuse to cooperate with the decisions that have been made for her. But what’s the cost of this behavior, given that such defiant acts are seen as hostile and offensive in a society where they imposed decisions are supposed to be accepted without question?

Just as Tehran’s air quality issues would benefit from a temperature inversion in which the oppressive prevailing hot air is forced upward, allowing cooler atmospheric conditions to settle in to wipe out the smog, Niloo believes she would benefit from a comparable metaphorical change in her own life. The “hot air” that’s been spewn by many of her family members and virtually all of the men in her life has stifled her when it comes to simply being able to live her life her way. Will the conditions present in her existence dissipate? It’s a forecast she would undoubtedly like to see come true.

When others impose themselves on us without our permission or consent, the effect can be maddening. The level of frustration and anger is often staggering. And, when we find ourselves struggling under conditions where it’s difficult to retaliate against, or even to counter, those excessive burdens, those feelings are frequently amplified. Moreover, when such situations are generally accepted – even sanctioned – by cultural norms, these scenarios can become unbearable. So, needless to say, for those who are independently inclined, like Niloo, dealing with such impositions can be utterly exasperating.

However, as vexing as these circumstances can be, we’re often left wondering what to do. Can they be overcome to arrive at a satisfactory outcome? Well, that depends on how readily we believe such situations can be rectified. And that’s important, given that our beliefs determine how our reality unfolds, a product of the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains these intangible building blocks shape our existence.

In a case like this, if we wish to attain a result to our satisfaction, we must believe that achieving it is truly possible. If we fail at this, however, we’re likely to be stuck with what’s being foisted on us. So what are we to do?

Understanding the complete range of beliefs involved in situations like this can be a valuable starting point, primarily because they’re seldom black and white. There are many in-between shades that can affect how circumstances unfold. For instance, beliefs associated with doubt can inflict considerable impact on these scenarios. No matter how strongly we may believe that amenable outcomes are attainable, if we allow doubt-based beliefs to figure into the mix, the hoped-for results can evaporate instantaneously. Therefore, isolating and eliminating any beliefs along these lines is imperative. Likewise, if we hold fast to beliefs in fears or limitations on what’s achievable, we’re likely to encounter comparable results. They, too, must be eliminated to get what we want, because, if they hold on, they’ll unduly interfere with the desired outcomes.

From where Niloo stands, these impediments could easily stand in her way, and there are even times when she seems to give them some credence in terms of how she responds. However, the more these obstructing beliefs attempt to impinge upon her, the more empowered she becomes in sweeping them away, difficult though that may be. She knows what she wants, and she’s determined to get it, especially since what she’s asking for is wholly reasonable.

By contrast, it’s curious to note how Farhad and Homa respond to Niloo’s challenges. They attempt to put up a brave, united front, believing that they’re entirely justified in implementing what they’re doing. But they certainly have their unspoken doubts, too, and they get in the way of them being able to pull off their schemes without hindrances, most notably as a consequence of the challenges put forth by their sister. Farhad and Homa resort to scorn, ridicule and even physical violence to counter Niloo’s arguments, growing increasingly defensive the more they’re openly confronted. And, when they begin to lose the support of Saba and Mahin, they become more desperate, but they also have increasing difficulty hiding their veiled shame. Suddenly the decisions that they saw as perfectly justifiable slam dunks are looking more questionable and in need of some much needed (and equally justifiable) scrutiny.

The ability to employ one’s power of discernment is crucial to this process as well, such as what happens when Soheil springs his surprise on Niloo. Prior to this, he has convincingly portrayed himself as a forthright, impeccably honest perfect gentleman, someone who would seemingly never think of trying to deceive Niloo or railroad her into a misrepresented scheme. He’s so smooth at this that he almost has her fooled, too. But, to her credit, Niloo is able to sense what’s going on before she’s in too deep, and her ability to detect these circumstances before becoming embroiled in them enables her to avoid the same kinds of conditions that her siblings are attempting to inflict on her, even if it’s presented in a more palatable, though nevertheless equally unfair, way.

Individual scenarios like the one Niloo faces serve as a vital starting point for initiating the process of changing the culture. The sort of grass roots effort involved in addressing Niloo’s case is akin to planting a seed that has the potential to promote change on a wider cultural scale. And, in a land where women increasingly want to enjoy the same kind of autonomy over their lives as their male counterparts do, these scenarios represent significant developments whose ripple effects could spread outward and be implemented more widely across Iranian society.

Movies that bring these issues to the public’s attention are thus important, for they help to enlighten those in need of hearing their message. As many films from overseas have shown in recent years, such as the recently released Indian offering “Fire in The Mountains,” women around the globe are increasingly tired of the prevailing disparity, standing up for themselves and no longer automatically capitulating to what others want (particularly men) just because they say so or are invoking traditions that are fast falling by the wayside. Matters of fairness and equality deserve to be heard, and pictures like this help to do just that.

Though somber and slow-moving at times, this 2016 domestic drama from Iranian writer-director Behnam Behzadi (now available for streaming) spotlights the one-sided attempts at imposing economic, career and living arrangement decisions on single women by their families, especially those who are married, and by men in particular. Like many films from Iran, the narrative here tends to over-explain things at times, but, in all fairness, this release also successfully resists the temptation to spoon-feed its audiences, relying on showing more than telling to make its points. This Cannes Film Festival nominee for the Un Certain Regard award serves up a story of inspiring assertiveness in the face of unfairly oppressive conditions, a story that’s sure to light a fire under those who feel repressed, making an impassioned case in favor of principles that are, and have long been, noticeably absent. This is truly an uplifting tale for women everywhere who feel needlessly put upon in simply trying to live their lives as they see fit.

When basic considerations like those addressed in this film go ignored, at some point they may emerge in a forceful, perhaps even exaggerated form. Such powerful notions can be denied for only so long before they erupt, no matter how diligently others may try to suppress them. And, for women like Niloo, who have begun to more aggressively assert themselves around the world, we had better listen to what they have to say lest we face circumstances that could be difficult to manage if allowed to manifest uncontrolled. After all, it’s simply the fair thing to do, and who can realistically find fault with that?

Copyright © 2022, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.