‘The Whale’ offers lessons in radical compassion

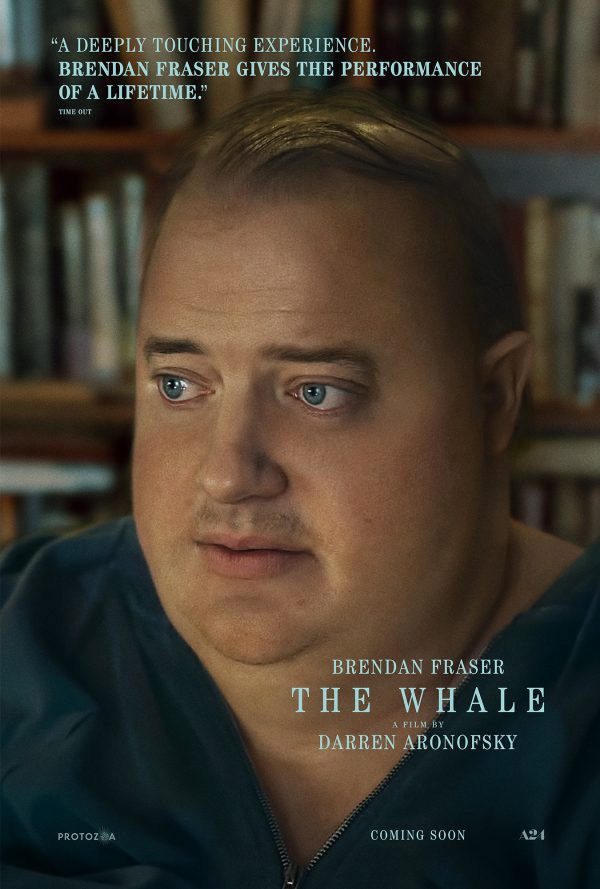

“The Whale” (2022). Cast: Brendan Fraser, Sadie Sink, Hong Chau, Samantha Morton, Ty Simpkins, Sathya Sridharan, Jacey Sink. Director: Darren Aronofsky. Screenplay: Samuel D. Hunter. Play: Samuel D. Hunter, The Whale (2012). Web site. Trailer.

Charlie’s embarrassment runs deeper than his looks, though; he’s also ashamed of his sexuality. As a gay man who was once married and fathered a daughter, he impulsively left his family to pursue a same-sex relationship with one of his students, a romance that, sadly, ended in his partner’s tragic death. It was an event that drove him to extreme binge eating, significantly swelling his already-hefty body size. It’s something he still does, too, consuming food so rapidly and so uncontrollably that his ravenous appetite nearly causes him to choke when he sits down to eat. This compulsion has left him with an assortment of health issues, such as out-of-control high blood pressure, congestive heart failure and severe mobility trouble.

And, no matter what Charlie does, he seems fundamentally incapable of resolving the challenges before him. It doesn’t help that he refuses to seek serious medical help, either, leading onlookers to believe that he’s simply given up on life, merely waiting for the end to come. Of course, when one considers his opinion of himself, that’s not particularly surprising; his self-esteem is virtually nonexistent, an outlook driven by a view of himself based on the assumption, “Why would anyone want to have anything to do with me?” Some might see this as wallowing in self-pity, but others would more astutely see this as a case of someone unable to address matters that are simply too big for him to handle, a view metaphorically mirrored by his immense stature.

Those closest to Charlie try to help him out, but they often look on in futility. That’s perhaps most apparent in the reactions of his friend and caregiver, Liz (Hong Chau), a nurse and the sister of his late partner. She does her best to offer care and compassion, but she often ends up frustrated over Charlie being his own worst enemy. Then there’s Thomas (Ty Simpkins), a door-to-door fundamentalist missionary who believes he was meant to show up in Charlie’s life to save his soul, a gesture he politely declines, despite his would-be savior’s repeat unsolicited visits.

The comparatively genial meetings with Liz and Thomas are more than offset by the considerably more antagonistic, cold-hearted visits from Charlie’s long-estranged teenage daughter, Ellie (Sadie Sink), whom he hasn’t seen since deserting her when she was eight years old. Ellie wonders why her dad has unexpectedly sought to resume contact with her, yet she reluctantly complies with his request, despite spewing more than her share of bile about her opinion of him and his long-ago act of abandonment. In fact, about the only thing that keeps her coming back for further visits is his promise of an inheritance meant exclusively for her, a bequest that may well be coming her way sooner rather than later given his rapidly declining health. Nevertheless, even that isn’t enough to stop her sniping, callously showering her father with unrelenting venom about his weight, his sexuality and what she sees as his innately pathetic existence.

Ellie’s sentiments are echoed by those of her mother, Mary (Samantha Morton), when she pays an unexpected visit to Charlie after hearing about his meetings with their daughter, encounters that he was hoping to keep off her radar. She’s especially upset when she learns that Charlie has compiled an impending windfall for Ellie after years of claiming that he had no money to give them in the wake of their separation. It also angers Liz given all the years of charitable care she had been so freely providing him. And this revelation is yet another reason to fill Charlie with regrets and self-loathing, further lowering his sense of self-worth. It’s almost enough to finally push him over the edge.

No matter how all of this plays out, however, Charlie recognizes the good in what these others say and do, even when their treatment is seemingly hurtful. He can see that there is concern for him in their hearts, regardless of the package in which it comes wrapped. It provides him with a sense of love, warmth and support, backhanded though their delivery may be. These are qualities that he’s been unable to provide himself, and they come at a time when he needs them most. That’s quite an insight for someone who has been the target of such relentless bullying and unbridled ridicule. We should all have such a sense of enlightened perceptiveness under conditions like these.

Almost universally, outsiders see Charlie’s existence as pathetic. But, then, he sees himself the same way, so is it any surprise that his reality would be imbued with qualities that embody such an outlook? He hates himself, and so he has created an existence that he also hates, filled with hateful conditions and individuals who, at least superficially, appear to hate him and how he lives. He even engages (and has long engaged) in actions that validate this perspective. However, even though this viewpoint appears to be the primary thrust of his thinking, it’s not the only one that’s present in his consciousness, and those other notions also figure in to how his reality plays out.

For example, as noted earlier, there’s a part of Charlie that believes in the innate goodness in others, even if their words and deeds don’t always outwardly reflect that notion. He sees that inherent care and compassion directly mirrored back to him, for instance, in the behavior exhibited by Liz and Thomas. He also sees it in the actions and comments of Ellie and Mary, even if those underlying sentiments are drenched in anger and frustration, masking their true feelings.

Charlie’s response to their reactions, as well as to his own views of himself, are also equally convoluted and seemingly contradictory. And, given what he’s created for himself, it’s no wonder he often doesn’t know how to effectively respond to his circumstances. The conditions he’s manifested are so dire and so fraught with huge ramifications that he doesn’t know which way to turn first. Indeed, how can one successfully respond when the scenario appears to be just too big to resolve?

This is where Charlie looks to the input of others to help guide him, but that’s not always a wise practice, either, since the feedback is so blatantly contrary. Liz and Thomas, for example, try to help and give him the support he needs to work through his challenges. Ellie and Mary, meanwhile, unapologetically spread their scorn, often reflecting the widely embraced attitudes of fat-shaming and homophobia held by segments of the public at large. What is one to make of a conundrum like this?

The natural inclination for many who feel so conflicted is to want to hide, and what better way is there to do that than to bury oneself under massive layers of camouflage, like those provided by huge slabs of body fat. If Charlie doesn’t want the world to see who he is, there’s likely some part of his consciousness that wants to make a concerted effort to conceal the image of himself that he so detests. True, he may have perpetrated some acts that are far from acceptable, but it’s also obvious that heʼs an individual in a great deal of pain that he’s unable to resolve. Who wouldn’t want to hide under circumstances like these?

The fallout from that can be significant, too. The shame and embarrassment that Charlie feels make it almost impossible for him to be honest, both with himself and with others. That has to be a horrible feeling, and it may even make one question one’s worthiness of receiving the genuine kindness of others. This leaves Charlie susceptible to a continuing cycle of self-destructive beliefs and behavior, causing him to spiral ever downward into an abyss of misery from which he may never recover.

Can Charlie bounce back from his despair and a destiny that appears inevitable? That’s hard to say, but one thing is for sure: For him and anyone else similarly situated, it comes down to his beliefs and which ones he chooses to embrace. It’s never too late to change course, but one must have the courage, conviction and desire to do so. And, given the state of his physical and emotional condition, it’s crucial that he make up his mind soon, while he still has the time, opportunity and wherewithal to make a meaningful and impactful change. But the key question here is, “Will he do it?”

Of course, it would be tremendously helpful if others would get on board with him and offer the support and encouragement he needs. And this, if nothing else, is one of the key messages of this film, a heartfelt plea to provide those in need with the care and compassion they require when attempting to deal with challenges that seem patently overwhelming. Doing so may not always be easy, especially when one is tempted to give in to the kind of judgmentalism that frequently accompanies widely held beliefs about what’s acceptable in areas like body positivity and alternative sexuality (let alone in one’s view about somebody who embodies both qualities). But, on this point, we each have the capacity to choose to blindly follow the pack or to let our natural humane instincts to surface. Most of us would never think of being cruel or critical toward those suffering from the detrimental effects of substance abuse, financial difficulty or health conditions, so why would anyone do the same when it comes to addressing another’s obesity or sexual orientation?

Amazingly, I’ve been shocked by some of the hurtful reactions I’ve seen to this film from both viewers and critics. How anyone could embrace such vile viewpoints is difficult for me to fathom, let alone to make those sentiments plainly known in print or on the internet. “The Whale” genuinely pleads with us to attempt walking in the shoes of someone like Charlie to gain a greater appreciation of what individuals like him must endure. Yet, considering some of what I’ve read, it’s painfully obvious that many have missed the point of the picture – and an opportunity to learn and grow from the experience. Those are the ones who I truly feel sorry for. As a plus-sized gay male myself, I know what it’s like to be on the receiving end of such disrespectful treatment, and I can honestly say how devastatingly painful it is. No one should be subjected to such undue ridicule, especially when their name-callers have a chance to learn from films like this that show the effects their behavior have on their victims. One can only hope that they don’t miss out on an opportunity to learn such a valuable life lesson.

The old saying about glass houses and not throwing stones seems fittingly apropos here, both for the characters in this story and the ever-so-cynical critics who have so unfairly and recklessly flung their condescending assessments toward this offering. Director Darren Aronofsky’s latest tells a heartbreaking and heartwarming tale of someone attempting to resolve challenges that often seem insurmountable. At the same time, however, we also see a quietly hopeful character who somehow manages to see the best in people, despite having often been the object of cruel, unapologetic scorn and has consequently been needlessly hard on himself. It’s an outlook that many of us are unable to imagine, let alone sustain, but believing that such a benevolent attitude is our natural tendency – despite considerable seeming evidence to the contrary – is a true gift and one of the tremendous attributes of this film. Now if Charlie could only come to embrace the same view for himself.

This thoughtful, insightful picture gives us much to contemplate, reminding us to make the most of our beliefs during the short time we have in our lives. It can be a hard watch at many points during the story, emotionally grabbing and shaking viewers in getting its points across. Admittedly, there are a few segments in which the dialogue comes across as somewhat awkward and stilted (even though the rationale behind such instances ultimately becomes apparent). But this modest shortcoming is more than made up for by the film’s superb ensemble cast (arguably the best I’ve seen this year), with stellar performances by Fraser (who’s truly deserving of this year’s best actor honors) and a fine crew of supporting players, including Sink, Chau, Morton and Simpkins. The film is also noteworthy for its exemplary achievements in makeup, particularly the enormous body prosthetics created to portray the protagonist’s massive stature, special effects that required hours to apply before each day’s shoot. This moving tale is indeed designed to draw out the compassion in others; let’s just hope it does.

“The Whale” has received more than its fair share of accolades thus far, though, in my view, it’s been somewhat shortchanged in this season’s award competitions. Most notable among the honors it has received are the best actor nominations Fraser has earned in the Golden Globe, Critics Choice and Screen Actors Guild Award competitions, as well as a SAG Award nod for Chau. Additionally, the picture has captured Critics Choice Award nominations for best hair and makeup, best young performer (Sink) and best adapted screenplay for writer Samuel D. Hunter’s script of his 2012 stage play. The film is currently playing theatrically.

Life provides us with opportunities for taking on tremendous challenges, life lessons designed to help us grow and develop as individuals. Sometimes, though, we may bite off more than we can chew, leaving us ill equipped for overcoming what we’re presented with. Under those circumstances, we may quickly find ourselves unable to tread water, increasingly running the risk of sinking. At times like this, we need someone to throw us a lifeline to help us stay afloat, not criticism about our inability to swim. “The Whale” provides us with a cinematic analogy to that situation, one that we should all take to heart, a valuable lesson that just might help us to save a life at a time when such compassionate assistance is truly needed most.

Copyright © 2022-2023, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.