‘Living’ breaks the chains of limitation

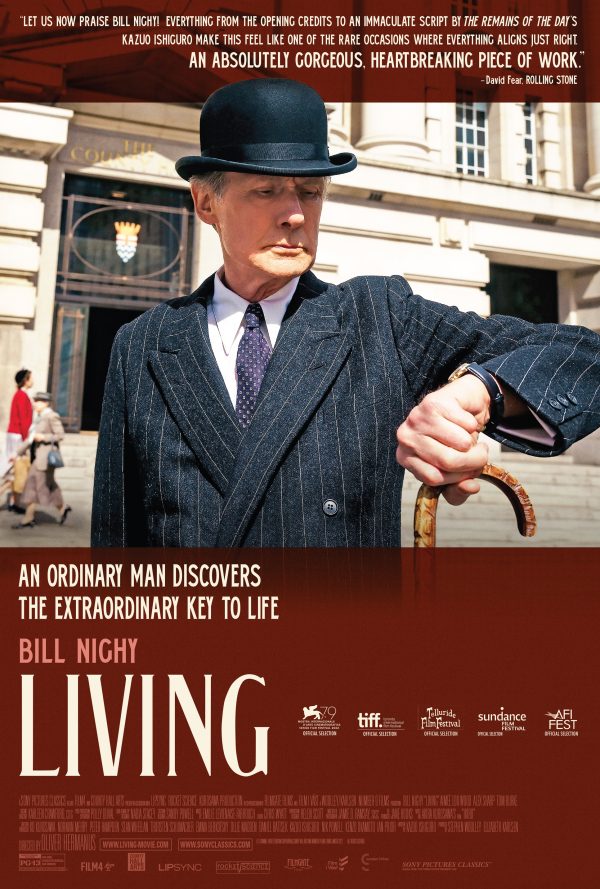

“Living” (2022). Cast: Bill Nighy, Aimee Lou Wood, Alex Sharp, Adrian Rawlins, Hubert Burton, Oliver Chris, Michael Cochrane, Anant Varman, Zoe Boyle, Lia Williams, Jessica Flood, Jonathan Keeble, Patsy Ferran, Barry Fishwick, Tom Burke, Nichola McAuliffe, Thomas Coombes. Director: Oliver Hermanus. Screenplay: Kazuo Ishiguro. Source Material: Akira Kurosawa, screenplay, “Ikiru” (1952). Web site. Trailer.

The environment in which Mr. Williams operates reflects this meticulously organized worldview, too. His daily train commute to downtown London from his home on the city’s outskirts never varies. Upon arriving at work, he dutifully extends a properly deferential greeting to his superior (Michael Cochrane), despite being routinely ignored. He then walks into his office, which resembles a fortress built from towering stacks of long-accumulated (and often-unresolved) paperwork. And, once there, he’s surrounded by a coterie of colleagues – particularly Mr. Middleton (Adrian Rawlins), Mr. Rusbridger (Hubert Burton) and Mr. Hart (Oliver Chris) – who devotedly follow through on their respective work assignments with perfunctory exactitude. It’s all so very painstakingly ordered and predictable.

Moreover, Mr. Williams has become so accustomed to this way of life that he expects others to naturally follow suit. For example, when a trio of local community activists (Zoe Boyle, Jessica Flood, Lia Williams) approaches his department about obtaining approvals to build a neighborhood playground, he assumes they’ve attended to every last detail, a routine that has apparently been repeated with them for some time. And, if anything is missing, he doesn’t hesitate to send them on an unending wild goose chase – such as paying visits to other municipal departments – to square up any oversights, many of which invariably end up remaining incomplete or referred elsewhere. It’s frustrating for these well-meaning advocates when failure to comply with such petty details continually sidetracks them from moving forward with their project; after all, they see things like the playground as much-needed infrastructural improvements, given that the neighborhood children have no safe place to go for fun in their rundown section of 1953 London, an area that is still recovering from the devastation of World War II. But Mr. Williams sees rules as rules – and that there’s no way getting around them when it comes to ventures under his purview.

The few “aberrations” present in Mr. Williams’s world don’t seem to have much impact on him, either. This includes the influence of a pair of young associates – Miss Margaret Harris (Aimee Lou Wood), a perky, modestly effervescent colleague (and the only woman in his department) who, despite a strong career drive, understands that there’s more to life than work; and Mr. Peter Wakeling (Alex Sharp), a jovial, light-hearted new hire who has yet to be sufficiently indoctrinated into the regimen and culture of the civil service working world (and someone who also apparently has eyes for Miss Harris). Then, outside the office, there’s Mr. Williams’s ambitious, loyal, loving son, Michael (Barry Fishwick), and his thoughtful, caring daughter-in-law, Fiona (Patsy Ferran), both of whom moved in with Dad after the passing of his late wife. Michael and Fiona do their best to keep him company and to attend to his needs, though he often seems to be too preoccupied with his own thoughts and interests to pay them much attention. And, despite the sincere attempts of all these lighter spirits to reach out to him, he never seems to respond in any particularly acknowledging way.

Events take a turn, however, when Mr. Williams announces to his staff that he’ll be leaving work early one day. He’s vague about the reason, and they refrain from asking him out of respect for his privacy. But, as things turn out, it’s for an appointment to see his physician (Jonathan Keeble). And, not long after their consultation starts, the doctor reveals that the news isn’t good: Mr. Williams has late-stage cancer – and not long to live.

The diagnosis – devastating though it may be – is the first thing to get Mr. Williams’s attention in quite some time, shaking him out of his longstanding complacency. But, despite this knowledge and the profound impact it has on him, he can’t bring himself to openly discuss it with anyone, including his family, despite attempts at practicing how to deliver the news. So what’s next?

Mr. Williams’s colleagues are perplexed when he fails to show up for work the next day – as well as in the days that follow. They speculate about where he might be and when he might return, but, with no awareness of what went on the day he left work early, they’re mystified about what happened and what to expect.

So where does Mr. Williams go? Quite impulsively, instead of following his usual morning routine, he boards a train to a small English seaside resort. He stops in a local café, and, while there, he strikes up an impromptu discussion with Mr. Sutherland (Tom Burke), a would-be artist who has many aspirations but little to show for his efforts given his unapologetic penchant for debauchery. In the course of this conversation, Mr. Williams at last opens up about his declining health (and ironically to a relative stranger). He also says that he would like to make the most of what time he has left. But, in the wake of this revelation, he also makes a huge admission – he doesn’t know how to do that and seeks his new acquaintance’s input.

Considering Mr. Sutherland’s inclination to always be on the lookout for a good time, he proceeds to chaperone Mr. Williams on a night of decadence at the resort’s local nightspots. They visit bars, amusement arcades and even an exotic dance revue. But, even though these are new experiences for the hitherto-conservative bureaucrat, they’re not for him. He’s looking for something more meaningful, an opportunity that will give him a chance to make a difference and leave a legacy. However, just as he admitted to Mr. Sutherland at the café, he doesn’t know how to go about this, either.

Mr. Williams attempts to arrive at an answer by reflecting on his past, particularly events that were important to him in his youth and that he hasn’t pursued much over the years as he became more preoccupied with the everyday concerns of his work routine, musings that get him thinking. He then has a chance meeting with Miss Harris one day during his absence from work. They strike up a conversation and begin spending time together on a regular basis. He helps her land a new job that she had applied for, and they begin sharing thoughts about life, what it means and how it can provide meaning for each of us. Through those encounters, Mr. Williams develops a newfound appreciation for what makes life worth living. And it gives him an idea on how he can go about leaving that legacy that has become so important to him. But will he be able to accomplish his goal with what time he has left? That remains to be seen and whether he legitimately has a chance to learn what it means to truly make life worth living.

Choosing a broader perspective is entirely possible, provided we believe in the possibility. And that’s where the conscious creation process comes into play, the philosophy that maintains we draw upon the power of our thoughts, beliefs and intents in manifesting the existence we experience. Given Mr. Williams’s limited worldview, it’s doubtful he’s ever heard of this school of thought and the limitless range of possibilities it makes attainable. However, considering his newfound ambition – to do something meaningful that would leave a legacy while he still has time left – there isn’t a better time for him to investigate what it has to offer and to put its principles into practice. He’s fast approaching a time when there is no tomorrow, so he’d be wise to get down to business.

With little experience in letting go, and being anxious to learn how to do so, he’s certainly wise to leave himself open to exploring his options, something he does eagerly by breaking his routine, asking others for help and cutting loose for his evening of unrestrained freedom with Mr. Sutherland. And, even though everything he initially tries out doesn’t work, at least he’s getting practice at loosening up that tightly buttoned-down collar. That’s a first step – and an ambitious one at that – one for which he is to be commended, no matter how much it startles or inconveniences others, including those close to him. Indeed, the first move in striking out in a new direction is to take bold steps in connection with that notion, something he certainly does.

Mr. Williams is also to be applauded for having the wisdom and insight into recognizing what does – and doesn’t – work for him. By employing his powers of discernment, he’s able to identify which manifestations are in line with his most heartfelt beliefs, those that harmonize with the nature of his true self, his authentic being. It’s why he’s able to quickly recognize that, despite the fun of his night of debauchery, it’s not how he wants to spend the remainder of his days, simply because that’s not who is deep down inside. He may be willing to cast off the shackles of his old life, but that doesn’t mean he’s willing to veer off into a new way of living that doesn’t align with his true persona.

That’s when he begins to explore other options, looking for those that will give him genuine satisfaction and fulfillment. He’s also wise to draw into his life those who can help guide him through that journey. His affiliation with Miss Harris, for example, provides him with a source of inspiration and a sounding board for exploring new possibilities. This is also true, to a lesser extent, with Mr. Wakeling. And, in appreciation for the assistance of these colleagues, Mr. Williams just might be able to do a little something for them. While gratitude has never been one of his particularly strong suits, he now has a chance to implement it to say thanks for his cohorts’ generosity of spirit, an opportunity to return the favor, a gesture inherently brimming with the fulfillment and satisfaction he has been searching for. If those aren’t laudable creations in the spirit of meaningful manifestation, I don’t know what are. And getting this in under the wire is even more impressive, a fine example of making the most of what temporal resources one has left.

By implementing these measures and learning the ways of this mode of thinking, Mr. Williams truly discovers that the chains of limitation can be broken and how to do so. That’s a big lesson for any of us, especially for someone who has spent his life believing that such possibilities were incapable of being realized. However, his experience lends ample credence to the notion of “better late than never,” even when it comes to learning valuable concepts about the nature and quality of existence. Well done, kind sir.

Based on the film “Ikiru” (1952) by acclaimed Japanese director Akira Kurosawa, this English adaptation of that work by South African filmmaker Oliver Hermanus faithfully re-creates the touching story presented in that picture in a setting a world apart from the original. It’s a heartbreaking yet heartwarming tale about the earnest sincerity of one determined to do good under trying circumstances and a tight timetable. While the storytelling style here may initially seem scattered, episodic and unconventional in some respects, there comes a turning point where the reasons for this become apparent, leading viewers (as well as the protagonist) to a new level of understanding in what proves to be a truly moving final act, an approach often used by Kurosawa and lovingly reproduced in this fitting cinematic homage. This is the kind of movie that will definitely appeal most to those of a certain age (i.e., those fast approaching their own finish lines), and it’s one that will almost certainly grow on audience members the further they get into it, even if it doesn’t garner widespread general appeal. The standout aspect of this production, of course, is Nighy’s stellar performance, one that has, thankfully, finally yielded ample, well-deserved recognition for this long-overlooked actor. It’s a portrayal backed by a fine supporting ensemble cast, gorgeous cinematography, and the excellent adapted screenplay of Kazuo Ishiguro, who previously distinguished himself in such works as “The Remains of the Day” (1993) and “Never Let Me Go” (2010). And don’t be surprised if this one evokes a few tears along the way, a sure sign that the inspiring and emotive message of this offering is truly getting through, successfully presenting viewers with insights into the true meaning of living.

Even though “Living” is one of the late comers among awards season releases, it’s nonetheless well worth the viewing time, and it has earned its share of well-deserved recognition. That’s particularly true for Nighy’s superb performance, capturing best actor nominations in the Golden Globe, Critics Choice, Screen Actors Guild, BAFTA and Academy Award competitions. Its excellent adapted screenplay also earned the picture Critics Choice, BAFTA and Academy Award nominations, as well as a BAFTA Award nod for Best British Film. And the National Board of Review has generously selected “Living” as one of its Top 10 Independent Films of 2022. The film is currently playing theatrically.

Copyright © 2023, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.