‘Our Father, the Devil’ asks, ‘When is it too late to do the right thing?’

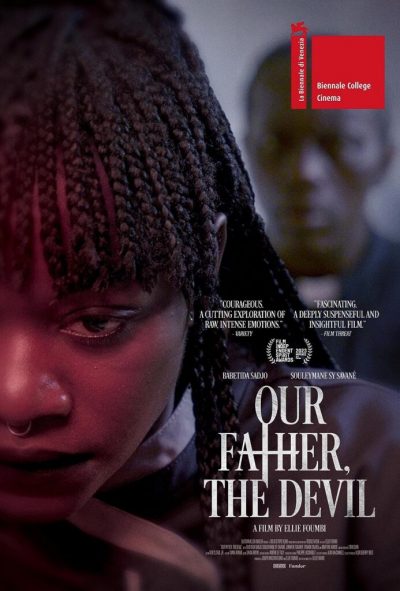

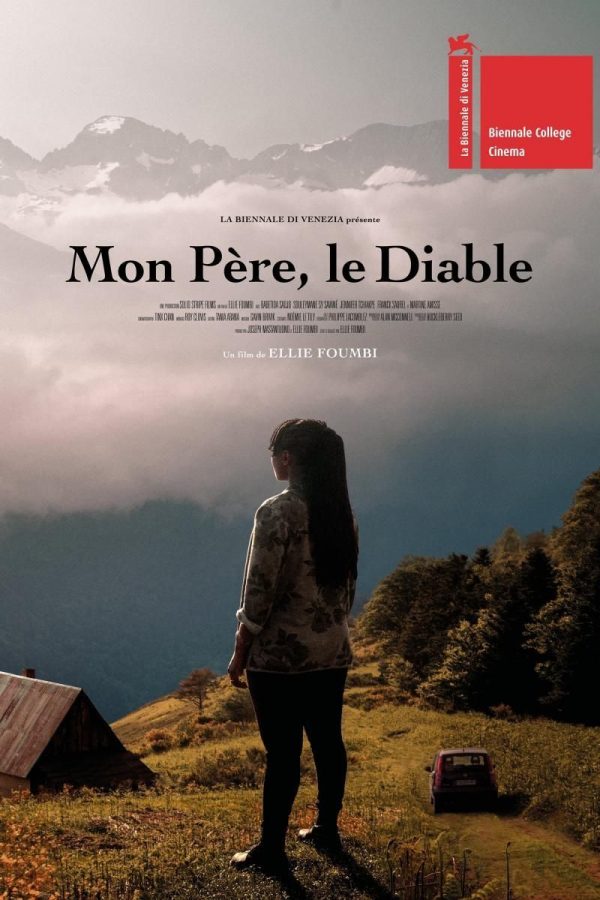

“Our Father, the Devil” (“Mon père, le diable”) (2021 production, 2023 release). Cast: Babetida Sodjo, Souleymane Sy Savane, Jennifer Tchiakpe, Franck Saurel, Martine Amisse, Maëlle Genet, Hiba el Aflahi, Valentin Fruitier, Maxence David, Patrice Tepasso. Director: Ellie Foumbi. Screenplay: Ellie Foumbi. Web site. Trailer.

That’s something new for Marie, though, given her deeply troubled past. As a refugee from Guinea, she managed to escape the atrocities and captivity of a ruthless warlord responsible for the brutal murders of entire villages, including those of her own family. She somehow managed to survive those heinous crimes, finally getting away after the monstrous strongman was himself killed. Yet, as much as she’s managed to put that behind her, there are still times when recollections of those painful days unexpectedly surface, prompting her to go into full-blown defensive mode, sometimes even as a result of small and insignificant events that pose no discernable threat other than reviving her memories.

One area in which Marie seems to have more than her share of apprehensions is in her dealings with men, especially when they try to get to know her, no matter how gentlemanly they may be. That’s most noticeable with a flirty but eminently courteous bartender, Arnaud (Franck Saurel), who works at the café where she often spends her free time. She routinely gives him the brush-off, despite his polite persistence and seemingly harmless efforts to befriend her. Marie even grows anxious with Nadia when she nudges her make the effort to go out and meet men. She’s a beautiful, young, available woman, yet she remains resolutely tight-lipped about the reasons behind her reticence.

In all, though, Marie has apparently adapted well considering what she endured. But that all changes one day when she arrives at work and hears an eerily familiar voice in an adjacent room. It strikes an unnerving chord with her, so she stealthily moves toward the source of her uneasiness and finds it in the personage of a newly arrived priest, Father Patrick (Souleymane Sy Savane), who’s understatedly delivering a homily to the residents. But what makes the revelation so chilling is that the cleric appears to be the second coming of Sogo, the guerilla who murdered Marie’s family and took her captive.

When Marie at last meets Father Patrick, she’s convinced that he’s the warlord who committed such terrible acts of barbarism. However, he, in turn, doesn’t appear to recognize her; either his reaction is truly sincere or he’s quite an actor. No matter what the case, though, Marie isn’t buying any of it. She researches the matter further online, reviewing photos that appear to verify her conclusion and prompting her to believe that reports of Sogo’s demise were in error, that he must have somehow faked his own death on his way to being reborn as the fraudulent Father Patrick.

Marie struggles to contain herself at work, but the terror induced by his reappearance frequently causes her to shake uncontrollably. Whenever she is in his presence, she seethes with anger, despite his apparent lack of a response to her mood. It soon becomes obvious that she’s nearing a breaking point. And, when the two of them are alone in the kitchen one evening after dinner, she makes her move – striking him with a pan, knocking him out and taking him back to her cottage as her prisoner.

With her captive bound and tied, Marie confronts him upon regaining consciousness. He insists that he’s not Sogo, that she’s making a terrible mistake. He pleads with her to let him go, but she’ll have none of it, especially when he periodically lapses out of character and lets clues to his true identity slip out. He continues to deny who he is, and, when that doesn’t work, he tries to win over Marie with a combination of tales of his godly self and sob stories about his troubled youth. And, when the going gets especially tough, he seeks to assuage his captor with confessions of his sins and efforts at seeking atonement after having successfully found Jesus.

In the meantime, Marie avails herself of this opportunity to exact retribution. She turns the tables on her onetime tormentor, inflicting upon him the same kinds of torture that she believes he perpetrated against her. In essence, she begins to become everything that he was, something at which she appears to be more adept than one might realistically think she should be. Indeed, exactly how did she become so seemingly uncharacteristically proficient at this sort of behavior? Under conditions like these, in which she insists he’ll burn in hell for what he did, couldn’t the same be said for her as she carries out her acts of apparently well-practiced vengeance?

As time goes by, however, Marie doesn’t appear to have an end game in place for this situation, despite what seem like threats (albeit empty ones) to the contrary. Indeed, how is she to extricate herself from this scenario? The heat soon gets turned up, too, when the local police begin inquiring about Father Patrick’s mysterious disappearance with the staff of the senior center, given that’s where he was last seen. The facility’s manager, Sabine (Maëlle Genet), subsequently instructs all of her employees to fully cooperate with authorities in their investigation, including questioning each of them about what they might know. Needless to say, with that, the noose begins to tighten around Marie’s neck, but what is she to do? And, given how everything has unfolded thus far, how will all of this ultimately play out? Even Jesus might have difficulty figuring this one out, but, then, He just might have a role to play in its resolution, too.

Under circumstances like these, many of us might readily say that Marie and Father Patrick/Sogo get whatever they deserve. And, considering what happened, those sentiments arguably have merit. But, at the risk of playing devil’s advocate (pun intended), is that the best response we can come up with? Is an eye for an eye the wisest course? It might make some of us feel as though justice has been done, but couldn’t it also be seen as appeasement for the vengeful? Is that what we really want to come out of this, especially among those of us seeking the creation of a better world or in invoking the name of spiritual teachers like Jesus, whose name is repeated frequently in this story? If that’s the case, then perhaps we need to employ a different, more unconventional approach.

Doing this, however, may also require that we adopt different beliefs, including some that many of us may find hard to swallow. Notions like forgiveness and redemption come to mind, particularly when they’re accompanied by humility and atonement and backed by sincerity. These are ideas that many of us recognize as lofty, noble, praiseworthy concepts, but, in the face of everyday life and the transgressions that can be perpetrated against us, they’re often looked upon as philosophical principles that we don’t have the luxury of indulging in a practical sense. But is that really true? If so, then why have we devised such notions in the first place – as something genuinely attainable or as idealized conceptions that can never be realistically fulfilled?

If the foregoing views have sincerely been conceived of, then there must be some part of us that believes they’re achievable. And that’s important to consider, given that our beliefs play a vital role in the manifestation of our existence, a product of the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains these intangible resources are responsible for the materialization of our reality. Granted, the fulfillment of these ideals may not be easy (especially for those who have never heard of or embraced this way of thinking), but the mere fact that they exist within our consciousness suggests that their realization is indeed somehow possible. This is particularly true when we take into account the teachings of spiritual leaders like Jesus and others, who have attempted to enlighten us to the possibility of seeing these notions brought into being despite what the naysayers contend.

To be sure, giving credence to the value of notions like forgiveness, redemption and atonement requires us to stretch the thinking that many of us currently adhere to. Many of us have been long tied to beliefs that assert we should “do to them whatever they do to us.” But isn’t that locking us into a cycle from which escape is exceedingly difficult? Where is the space for personal growth, spiritual evolution and broadened enlightenment in a relentlessly intractable scenario like that? Think of where we’d be if we don’t make allowances for change like that. Is that what we truly want for ourselves down the road? And, if so, why do we even bother trying to improve upon ourselves if we can’t get past self-imposed impediments like this?

It must be noted, however, that situations like this are indeed two-way streets. Forgiveness and redemption of those who have wronged us mean little if there’s no heartfelt sense of atonement on the part of those who have engaged in these grievous acts. It’s hard to absolve evildoers who have no remorse for their misdeeds. But, for those who genuinely do, it’s equally unfair to continue blaming them for what they have sincerely admitted was wrong. If we fail to come through on that front, it amounts to nothing more than a case of “it’s not enough to apologize any more,” and goodness knows we see plenty of that phony self-righteousness going on in society and in the media these days.

Making outcomes like these possible thus requires us to become better at learning how to let go, how to leave behind what no longer serves us, like longstanding grudges. Again, this is something that is far from easy, given that we have long been taught – and have since long come to believe – that this is what we’re supposed to do in situations like this, with more egregious acts being made to bear more severe and more persistent resentment. However, if we’re indeed desirous of moving on to those more perfect worlds we’ve been told so much about, when are we going to make a concerted effort to change our ways to bring about that result? We certainly won’t do so by desperately hanging on to old ideas with our sharpened claws extended, no matter what sense of satisfaction it might provide us in the short term.

If we continue to assert our aspirations to attain something higher for ourselves and our existence but do nothing in our beliefs, acts or deeds to achieve such an outcome, then we’re merely paying lip service to a hollow concept, no matter how much we might contend to the contrary. In light of that, then, if we sincerely want to see this dream fulfilled, at some point we have to swallow our pride, put our money where our mouth is and step up to make these objectives realized. If we don’t, we’ll never progress, and no amount of protesting that the devil made us do it will ever change things.

They say it’s never too late to do the right thing. But how far does that extend? Does it include atoning for the commission of heinous crimes? Or must one be perpetually forced to pay for those transgressions, even with the admission of heartfelt regret? Those are the heady questions raised in writer-director Ellie Foumbi’s brilliant debut feature, a gripping tale that will keep audiences on the edge of their seats. The picture’s mutilayered narrative keeps viewers (and characters) guessing, almost as if both are being toyed with by the filmmaker, but this is carried out so skillfully that one can’t help but remain riveted. The story is effectively fleshed out by the film’s superb ensemble cast (especially the two leads), backed by inventive cinematography, exceedingly clever film editing, a fine background score, an array of subtly symbolic touches and a surprising amount of strategically placed, well-executed comic relief. Admittedly, there are some modest pacing issues in the middle, but they’re usually employed to set up one of the picture’s many smartly developed plot twists. This 2022-23 Independent Spirit Award nominee for best feature, as well as the recipient of many film festival award wins and nominations, is a well-kept cinematic secret that genuinely deserves wider attention, both as a thoughtful meditation and as an engaging drama. And, by all means, do not let the title scare you off! This is not a horror film per se, even though it deals with subjects that are in themselves horrific. “Our Father, the Devil” is an important, insightful offering not to be missed. The picture has primarily been playing the film festival circuit and is currently in limited theatrical release, but it’s well worth the effort to find it.

Copyright © 2023, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.