‘Us’ forces us to take a look at ourselves

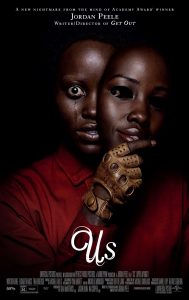

“Us” (2019). Cast: Lupita Nyong’o, Winston Duke, Shahadi Wright Joseph, Evan Alex, Elisabeth Moss, Tim Heidecker, Cali Sheldon, Noelle Sheldon, Yahya Abdul-Mateen II, Anna Diop, Madison Curry, Ashley Mckoy, Napiera Groves, Alan Frazier. Director: Jordan Peele. Screenplay: Jordan Peele. Web site. Trailer.

Have you ever thought what it might be like to meet yourself? How we see ourselves can be an eye-opening experience, especially if what we observe doesn’t match our expectations. What we encounter could be significantly different from what we believe about our being, our attitudes and our behavior. But, on closer inspection, we may be surprised to see that it’s exactly who we are at our core, a scenario that gives us much to assess, some of which could be at odds with who we’d like to think we are. Such is the case for a seemingly average American family in the revelatory new smart horror release, “Us.”

It’s summertime, and the Wilson family is ready for their annual trip to their vacation home near Santa Cruz, California. Parents Adelaide (Lupita Nyong’o) and Gabe (Winston Duke), along with their children, Zora (Shahadi Wright Joseph) and Jason (Evan Alex), look forward to their getaway, but there’s an undercurrent of uneasiness underlying the trip, especially for Adelaide. Gabe does his best to allay his wife’s anxiety, but she quietly continues to harbor her apprehension.

Adelaide is particularly concerned about the family’s planned daytrip to the beach. It’s a popular tourist destination with an adjacent boardwalk and amusement park. With so much to do, it’s the kind of place that should make for a good time, but Adelaide is full of trepidation about the outing because of an experience that happened to her there when she was a child. It was a traumatic incident that she’s kept mum about all these years, but, when Gabe presses her about her hesitation, she finally opens up.

On a warm summer night in 1986, a young Adelaide (Madison Curry) visited the amusement park with her parents, Russel (Yahya Abdul-Mateen II) and Rayne (Anna Diop). At one point while her parents weren’t looking, the youngster inexplicably wandered off, walking into a funhouse with a Native American vision quest theme, one that challenges visitors to “discover yourself.” As she made her way through the structure’s dark and mysterious corridors, she came upon the kinds of elements typically found in these attractions, such as animated figures that pop out of the walls. Needless to say, these features startled the young visitor, but Adelaide’s biggest frights were yet to come.

When faced with an unexpected terrifying situation in an amusement park funhouse, young Adelaide Wilson (Madison Curry) reacts in fright to what she sees in director Jordan Peele’s “Us.” Photo courtesy of Universal Pictures.

While walking through the funhouse’s hall of mirrors, Adelaide saw something in the looking glass that took her by surprise – an image of what appeared to be herself with her back turned toward her. But then, quite unexpectedly, the figure turned to face her with bulging eyes and a sinister grin beaming from ear to ear.

Adelaide was so stunned by what she saw that she withdrew and stopped talking. Her parents took her to a therapist (Napiera Groves), hoping that counseling would draw out what happened and set her on a course of recovery. And, thanks to her development of an interest in dancing, an adolescent Adelaide (Ashley Mckoy) emerged from her isolation. But, even with the passage of time, the experience still haunts the now-adult Adelaide all these years later.

Gabe is stunned that Adelaide has kept everything locked up inside for so long, but, having now shared the experience, she seems moderately relieved. Consequently, to keep peace in the family, she agrees to go on the outing despite being on guard the whole time. She’s constantly on the lookout for anything unusual, and she has trouble relaxing, even while spending time in the company of her good friends Kitty (Elisabeth Moss) and Josh (Tim Heidecker) and their two daughters (Cali Sheldon, Noelle Sheldon). But, when the time comes to leave, she’s only too happy to pack up and go home.

What should be an enjoyable summertime vacation turns contentious when the Wilson family (from left, Lupita Nyong’o, Evan Alex, Shahadi Wright Joseph, Winston Duke) receives a visit from unexpected “guests” in director Jordan Peele’s latest offering, “Us.” Photo by Claudette Barius, courtesy of Universal Pictures.

Once back at the vacation house, though, things take a rather weird turn. First the power goes out. And then, lurking in the dark, Adelaide notices a family of four standing in the driveway, one whose members bear an uncanny resemblance to the Wilsons. They stand silently arm in arm dressed in red jumpsuits, each holding what appears to be some kind of pointed golden implement.

Gabe doesn’t think much of it and makes a friendly attempt to see what they want. But, when he finds out these apparent doppelgangers are anything but cordial, the situation turns contentious. The “copies” of Adelaide, Gabe, Zora and Jason, who respectively call themselves Red, Abraham, Umbrae and Pluto, break into the house and begin terrorizing the inhabitants, all for no apparent reason and without making any specific demands – that is, until Red begins to speak, informing her hostages who they are and what they want.

The unexpected appearance of a creepy-looking family (from left, Evan Alex, Winston Duke, Lupita Nyong’o, Shahadi Wright Joseph) places a damper on a summer vacation in the superb new smart horror release, “Us.” Photo by Claudette Barius, courtesy of Universal Pictures.

To say more would reveal too much, but suffice it to say that the Wilsons are not the only ones being confronted by their doubles. Everyone, it seems, is being met by their alternate selves. These duplicate beings bring a reign of terror to the world, emerging en masse from what appear to be subterranean tunnels whose existence was virtually unknown by the public at large. Most violently attack their surface world counterparts, while those who don’t join in the barbarism hold hands to form a human chain across the landscape (a gesture eerily reminiscent of the Hands Across America initiative organized to raise awareness about the homeless in the summer of 1986, the time when Adelaide had her traumatic amusement park experience).

But to what end is all of this transpiring? That’s what the Wilsons – and the rest of the world – are about to find out. And the answer will prove quite surprising, to both those on and off the screen.

“Red” (Lupita Nyong’o), the enigmatic doppelganger of a middle-aged housewife, makes life hell for her counterpart and her family in director Jordan Peele’s “Us.” Photo by Claudette Barius, courtesy of Universal Pictures.

“Us” is a film that raises almost as many questions as it answers. Director Jordan Peele has presented viewers with an intriguing cinematic puzzle, one that’s densely packed with ideas, themes and images and, consequently, is open to interpretation on multiple levels, all equally valid and none contradictory of one another. The key question in this is “What do you believe?”

There’s quite an irony in that, given that the same inquiry is central to understanding the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains we manifest the reality we experience through the power of our thoughts, beliefs and intents. In this case, though, the filmmaker is asking us to do as much work in that vein as he’s putting his characters through. In that sense, then, we’re not just being offered a celluloid example of the philosophy at work; we’re also being tasked with engaging in an exercise that allows us to see firsthand how it functions, with each of us given an opportunity to create a cinematic experience of our own, one based on the beliefs we hold about the material being presented to us. And, since conscious creation essentially maintains that we each create our own reality, we’re each going to do just that where this picture is concerned in terms of what we see, what we think about it and what we ultimately experience, all driven by our beliefs.

For the record, we actually do that when we see any movie (or actively engage in participating in any aspect of our existence, for that matter), but we usually take the circumstances and outcomes in those situations for granted, paying little attention to how they arise. Here, though, director Peele places that notion inescapably in front of us, impelling us to participate – consciously – in this exercise in reality creation. In that regard, we’re truly doing more than just watching a movie; we’re being given a metaphysical tutorial of sorts, one that, in the end, is enlightening, entertaining, thought-provoking and a hell of a lot of fun.

The unexpected arrival of mysterious visitors causes stress for middle-aged housewife Adelaide Wilson (Lupita Nyong’o, right) and her husband, Gabe (Winston Duke, left), in “Us.” Photo by Claudette Barius, courtesy of Universal Pictures.

While many viewers are likely to have similar takes on what they see, there will no doubt be instances where individual audience members come up with interpretations all their own. But that’s okay, considering the ample fodder that the filmmaker gives us to work with (not to mention the fact that we already do the same when it comes to our experiences in other life contexts). So what I offer here are my thoughts on what this picture is saying from a conscious creation perspective. And, in doing so, as I noted above, I’ll make an especially concerted effort to share my views without revealing any spoilers in the process.

The idea of a doppelganger is an intriguing one, a notion that has found its way into an array of subjects, ranging from mysticism and mythology to contemporary psychology. Given this level of pervasiveness, it would seem there must be something to it. But how many of us pay any real attention to it? We tend to ignore the concept until we find ourselves staring it in the face. Then what?

As a general rule, when we come face to face with a manifestation of our personal selves, our first question is usually to ask why it has materialized. What does it want? Is it trying to tell us something? And why now? Those are the questions on the minds of Adelaide and her family when their doubles first appear, and they find the experience frustrating due to the lack of ready answers. I think it’s a safe bet many of us would have comparable reactions. But, where the Wilsons are concerned, this becomes a bigger problem when their unexpected visitors start lashing out at them in violent and hostile ways.

Siblings Jason (Evan Alex, left) and Zora (Shahadi Wright Joseph, right) are forced to grow up a lot faster than they had probably imagined when faced with tremendous horrors in the gripping new offering, “Us.” Photo by Claudette Barius, courtesy of Universal Pictures.

Considering where the doubles are said to have originated, though, the answers might come a little more easily. Having emerged from a complex of underground tunnels into the light of the world aboveground, the doppelgangers are in many ways symbolic of our shadow selves, that little-seen part of our being that resides within the darkness inside us. It’s a portion of our being that’s largely ignored, if not summarily disparaged, looked upon as inherently inferior, perhaps even evil. It’s something most of us would much more readily disavow than acknowledge.

However, as much as we might try to deny this portion of our self, it’s nevertheless part of who we are. And, because of this, imagine how we would feel if we were to walk in its shoes. The lack of recognition and blanket rejection must be utterly unbearable. Given that, then, is it any wonder that the shadow self might eventually rise up and rebel, demanding to share in the same blessings we have come to enjoy from living life in the light? Of course, having spent its entire existence in the murky depths, is it also any wonder that our shadow might not know how to properly (i.e., civilly) seek equitable treatment? That would explain the barbarous behavior, now wouldn’t it?

If it’s possible to envision how this would work for an individual, imagine the same for a collective of similarly situated beings. This would account for the film’s mass uprising. But, speaking symbolically once again, this is an allegory for the outcasts of contemporary society – women, minorities, immigrants, the economically disadvantaged – everyone who has been denied the opportunity to revel in the bounty that comes from the abundance afforded by “life on the surface,” the benefits enjoyed by those who reside above those literally and figuratively relegated to the underworld.

Middle-aged housewife Adelaide Wilson (Lupita Nyong’o) fights back when confronted with extraordinary circumstances in the new smart horror release, “Us.” Photo by Claudette Barius, courtesy of Universal Pictures.

What’s even more telling in this scenario is the shoddy treatment the surface dwellers afford their below-ground counterparts. Those who live in the world below are dismissed, treated as if they don’t exist, a circumstance that can be applied both to our individual selves as well as society as a whole. And, sadly, this is “us,” a realization that makes the picture’s title fittingly chilling in light of its narrative and genre.

Considering that indifferent, condescending attitude – one created by the beliefs of those who hold it – it’s not too difficult to figure out what it would take to get their attention. And those who demand their share of the pie may not be as gracious in seeking it as those living in the light might think they should be (the one-percenters might want to take note of this). But, then, such outcomes are not unexpected when we practice un-conscious creation, an expression of the philosophy that results when we focus exclusively on manifesting what we want with no consideration for the consequences of our efforts, one often fraught with unintended and undesirable side effects. In this case, the resulting situation calls to mind a Biblical passage that’s prominently featured in the film literally, figuratively and symbolically, the text of Jeremiah 11:11: “Therefore thus saith the Lord: ‘Behold, I will bring evil upon them, which they shall not be able to escape; and though they shall cry unto Me, I will not hearken unto them.’” Yet another manifestation belief is fulfilled, one as reflective of the notions held by its adherents as anything seen in the funhouse hall of mirrors.

Admittedly, the foregoing is a lot to absorb, but, in actuality, it’s only part of the story. There’s potentially much more one can take away from this film, again, depending on the individual belief-based interpretations discussed earlier. I could say more, but I’d be straying too close to the spoiler territory I endeavor to avoid. So my recommendation is to watch this one for yourself and see what you get out of it. Personally, I can’t wait to screen it again to see what I may have missed the first time.

When middle-aged housewife Adelaide Wilson (Lupita Nyong’o, right) confronts her dubious double, Red (Lupita Nyong’o, left), the encounter quickly turns into a fight for survival in the gripping new smart horror offering, “Us.” Photo by Industrial Light & Magic, courtesy of Universal Pictures.

This richly layered, deftly nuanced smart horror offering tells a tale that gives the audience much to think about upon leaving the theater. Director Peele’s second feature defies “the sophomore jinx” that often plagues filmmakers who fail in their followup efforts after impressive debuts. The picture delivers an expertly crafted allegorical story that’s captivating and insightful, accompanied by great laughs and a few good scares without becoming gratuitous. This is all made possible by the superb performances of its excellent ensemble cast, most notably Nyong’o, who turns in some of her best on-screen work in this offering. And, as you watch it, take nothing for granted; everything has a purpose in the narrative, no matter how seemingly insignificant. As good as his first picture, “Get Out” (2017), was, the filmmaker has taken a quantum leap in his artistry and storytelling skills with this release, an accomplishment that puts him in a class by himself and will likely allow him to write his own ticket from here on out.

When we come face to face with ourselves, we’re forced into confronting what we see. No matter how much we might try to deny or disavow what we witness, though, we can’t realistically do so if we truly want to understand who we are at the center of our being. And, if we dislike what’s there, then we must take an earnest look at how it arose, analyzing and, if needed, changing the thoughts, beliefs and intents that gave life to it. After all, when we come right down to it, that’s us – whether we like it or not.

Copyright © 2019, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

Leave A Comment