‘My Dog Stupid’ wages a war on discontent

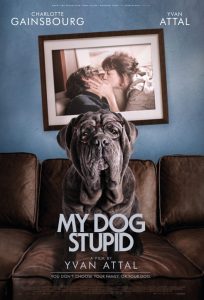

“My Dog Stupid” (“Mon chien Stupide”) (2019). Cast: Yvan Attal, Charlotte Gainsbourg, Eric Ruf, Pascale Arbillot, Ben Attal, Adèle Wismes, Pablo Venzal, Panayotis Pascot, Oscar Copp, Lola Marois, Sébastien Thiery, Franz Lang. Director: Yvan Attal. Screenplay: Stéphane Guillon and Dean Craig. Story: Dean Craig, Yvan Attal and Yaël Langmann. Book: John Fante, West of Rome. Web site. Trailer.

Most of us feel dissatisfied with our lives from time to time. Sometimes we have only a vague sense of what’s irking us, but often we have a clear picture of the irritation. Still, even with such an awareness, we frequently lack an understanding of how to fix the problem. Perhaps looking to the source of that discontent can help us figure out how to implement much-needed change. But, in doing so, we need to know where to look, something that may prove difficult – and surprising – as seen in the delightful and introspective new French comedy-drama, “My Dog Stupid” (“Mon chien Stupide”).

Henri Mohen (Yvan Attal) is one discontented guy. The 55-year-old onetime-successful French author hit a home run with a best seller 25 years ago, but he hasn’t written anything worthwhile (or lucrative) since then. True, his first work enabled him to live comfortably in a seaside estate that helped him escape what he saw as the unceasing drudgery of Paris, but there was a trade-off: That villa also became home to Henri and his family, whom he believes have grown progressively ungrateful over the years. With his wife, Cécile (Charlotte Gainsbourg), and their four ne’er-do-well adult children, Henri struggles to keep his sanity and self-respect amidst the incessant complaining and tribulations of a dysfunctional family who shows him no appreciation for the generous support and well-heeled lifestyle he has provided them.

So why are Henri’s wife and children so irritating? Well, for starters, there’s Cécile, who never seems satisfied with her life, a nagging, unrelenting discontent that she always seems to find a way to blame on Henri. Then there are his kids: Raphaël (Ben Attal), his eldest, drifts through life, spending his days smoking weed and cruising the internet for porn and women who are all too eager for a party, such as his principal squeeze, Marie-Lise (Lola Marois); Pauline (Adèle Wismes), Henri’s only daughter, who runs through money like water and spends most of her time fawning over her uber-macho boyfriend, Hugues (Oscar Copp), a former soldier who frequently brags about his allegedly heroic exploits in Syria; Gaspard (Panayotis Pascot), a surfer dude who’s barely hanging on in his college studies, even with the coddling assistance of Cécile, who does his homework for him; and Noé (Pablo Venzal), an honor student with a strong social consciousness who seems to have it all together but who also harbors a secret that doesn’t become revealed until authorities show up unexpectedly at the family doorstep one day. Nice relatives.

Once-successful author and discontented family man Henri Mohen (Yvan Attal) seeks to turn his life around through his impulsive adoption of a big, slobbering dog in the delightful new French comedy-drama, “My Dog Stupid” (“Mon chien Stupide”). Photo by David Koskas, courtesy of Distrib Films US.

The only family member who ever gives Henri the time of day is Noé, and even that support eventually becomes compromised for reasons outside of Henri’s control. The rest generally berate or ignore him, showering him with scorn or indifference. That leaves Henri alone with his thoughts much of the time, an opportunity to brood and to occasionally wax nostalgically about the one time in his life when he felt genuinely happy – his days in Rome when he was writing the book that would become his only success. He wishes he could return there and relive those glory days. But such hopes seem like a pipe dream now, leaving him to go back to the tasks that occupy his days – obsequiously fulfilling the family’s never-ending list of inconsequential shopping requests and attempting to write something meaningful.

Matters take a curiously quirky turn, however, when a surprise visitor shows up in Henri’s backyard one rainy evening – a big, slobbering dog that appears to be a stray. The canine, which resembles a shar-pei/mastif mix, wastes no time making himself at home, lumbering through an open door into the family residence and settling in, claiming a couch and gobbling virtually anything he can find to eat. This is in addition to his other voracious appetite: his need to indulge his insatiable libido, a hunger he readily inflicts on the human males he encounters, most notably, of all people, Hugues.

Needless to say, no one is particularly thrilled with the arrival of the unexpected house guest. Cécile, Pauline, Raphaël and Gaspard beg Henri to do something about the dog (just as they always seem to beg him to do something about anything they dislike), but, in this case, even Dad isn’t pleased with this new development. However, Henri’s attitude soon changes when he sees how lovable the dog can be. Admittedly, the pooch isn’t particularly bright, but he’s adorable nonetheless, a trait that becomes apparent when the only household member who takes a liking to him – Noé – manages to bring out his unique canine charm. At this point, Henri takes a shine to him as well and abandons all plans to pawn him off on the local SPCA. Instead, he adopts his newfound friend and names him, appropriately enough, Stupid.

Long-married couple Henri and Cécile Mohen (Yvan Attal, left, and Charlotte Gainsbourg, right) wrestle with the state of their relationship in the introspective French comedy-drama, “My Dog Stupid” (“Mon chien Stupide”). Photo courtesy of Distrib Films US.

Henri warmly welcomes Stupid into his life. As a longtime dog lover who has been without a canine pal for a while, he’s happy to have one in his life again (his last dog, Marcello, a beloved bull terrier, having been done in by the neighbor’s Doberman, Rommel). But, more than that, Henri sees the dog as a kindred spirit. Stupid was apparently thanklessly abandoned, with no one to care for his needs, for no good reason, circumstances to which Henri can readily relate. What’s more, since the family sees Stupid as an insufferable irritant, Henri’s adoption of his new friend represents a form of payback, a giant middle finger thrust into the faces of his ungrateful wife and children.

Even though Stupid gets on well with Henri and Noé, he’s seen as a royal pain by everyone else – so much so, in fact, that they gradually find reasons for moving out of the house to get away from him. In some regards, Henri quietly relishes these developments; with fewer people in the house, fewer demands are placed upon him, bringing him closer to retrieving what he believes to be the long-absent happiness he misses so much. But, as the house becomes emptier and emptier, it gives him pause to reflect upon himself, his life and what’s important, an exercise in introspection that proves revelatory. The canine catalyst prompts changes he never envisioned or considered. And now, with new insights in hand, he has an opportunity to reshape his destiny. Indeed, who would have thought so much could come out of adopting a big stinky dog?

By all accounts, Henri would appear to be the stereotypical hen-pecked husband (only, in his case, he would be more appropriately characterized as the stereotypical hen-pecked husband and father). The thoughtless treatment inflicted upon him is ostensibly egregious enough to generate heartfelt sympathy from even the most uncaring of onlookers. So why is this abuse happening to an apparently nice guy, one who is a good provider for his family and, as a successful author, should seemingly engender at least a modicum of respect?

Sunday brunch at the Mohen household turns contentious when family members (from left, Oscar Copp, Lola Marois, Adèle Wismes (back to camera), Ben Attal, Yvan Attal, Charlotte Gainsbourg) debate the future of an unexpected house guest in “My Dog Stupid” (“Mon chien Stupide”). Photo by David Koskas, courtesy of Distrib Films US.

The bad treatment Henri is being subjected to has been going on for a long time. As much as he dislikes it, he’s almost become used to it, accepting it as “just how things are.” But, in order for such circumstances to become so ingrained and persistent, something must be triggering them and enabling their perpetuation, a state of affairs that would appear to have been in place for quite some time. To that end, then, if Henri is convinced that this is his lot in life, then he must believe it to be so. And recognizing that is crucial, for those beliefs make this outcome possible, one of myriad potential results capable of being materialized through the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains we manifest the reality we experience through the power of our thoughts, beliefs and intents.

Henri’s case is indeed a curious one. One can’t help but ask, “Why would anyone want to create an existence like this?” For all practical purposes, Henri has manifested a state of unrelenting victimhood, one in which he’s continually taken advantage of, mercilessly put down and subjected to the ongoing capricious whims of others. Yet, at the same time, he’s thoroughly dissatisfied with what he’s wrought and would love to fight back. What’s going on with this seemingly contradictory conundrum?

As with any creation, our reasons for manifesting something are our own, and it’s nobody’s business to question or criticize them, no matter how pleasant or undesirable they may be. In many cases, difficult circumstances like these are often part of learning a particular life lesson, despite the hardships involved. Indeed, willingly allowing ourselves to be a victim is certainly one of the most challenging scenarios we can undergo. But, if we elect to endure such an experience, there’s got to be a purpose behind it. The question here, then, is, “What is it?”

Henri’s circumstances are further complicated by the fact that he doesn’t like being pigeonholed into the role of the victim. He wants to change it, even though he doesn’t appear to know how. It’s a frustrating stalemate, to be sure. So what can he do to get out of it?

Author and family man Henri Mohen (Yvan Attal, right) tries to motivate his weed-smoking, internet-surfing son, Raphaël (Ben Attal, left), to make something of his life in “My Dog Stupid” (“Mon chien Stupide”), now available for first-run online streaming. Photo by David Koskas, courtesy of Distrib Films US.

For starters, he must look to end the deadlock between these two sets of conditions, using his beliefs to draw the means into his life to make that possible. That calls for breaking the ice that has long been allowed to settle in, which is where Stupid comes in. The canine drastically shakes up life at the Mohen household, and that gets Henri’s foot in the metaphysical door so he can begin to assess the beliefs responsible for where he is and how he got there. The history behind Henri’s fate is crucial. If he wants to know how to change his life (and the beliefs that drive it), he must understand how he arrived where he’s at in the first place. That, in turn, means he needs to examine the beliefs that started this process and set it off on the autopilot it seems to have been on ever since.

Conducting such an analysis may not be easy, though. It truly can be a forest-for-the-trees experience. Which is why it’s so important to invoke beliefs that purposely shake things up, for such changes can expose manifesting thoughts and intents that we’ve been unable or unwilling to recognize, possibly for a very long time. That’s the process that Stupid helps initiate. It’s one that’s continued by the new developments that occur in Henri’s children’s lives. And it becomes most obvious in the relationship between Henri and Cécile, especially when she begins spending considerable time with one of Gaspard’s professors, Fabrice Mazard (Eric Ruf); what begins as a dialogue between them about the failing student’s grades soon morphs into something more, a change that certainly gets Henri’s attention.

With everyone dropping out of his life, Henri must ask himself what these changes represent. Even though he initially seems to enjoy the liberation that his newfound circumstances have provided, they also raise concerns, prompting him to question how he got to where he now is. While saying more here would reveal too much, suffice it to say that the roots of these conditions extend back far longer than he may have realized – long before he made the decision to adopt a big slobbering dog.

Bored housewife Cécile Mohen (Charlotte Gainsbourg) loathes the unexpected arrival of Stupid, the big, slobbering dog inexplicably adopted by her husband, in writer-director Yvan Attal’s delightful new French comedy-drama, “My Dog Stupid” (“Mon chien Stupide”), now available for first-run online streaming. Photo by David Koskas, courtesy of Film Distrib US.

Such introspection provides Henri much-needed perspective, as well as an opportunity to examine and rewrite the beliefs responsible for manifesting his reality. It gives him a chance to understand why his wife and family have treated him as they have, both in the past and presently. It helps unleash creativity in his writing that he hasn’t seen in some time, much to the delight of his publisher, Louise Breuvart (Pascale Arbillot). But, most of all, it enables an opportunity to reinvent his life, a goal he’s been chasing unsuccessfully for quite some time.

Those are significant developments. Some might say that it’s unfortunate it has taken Henri so long to discover the source of his discontent. And, on top of that, he may have some trouble coming to grips with that realization. But, if such revelations make it possible to implement changes that he has long sought to institute, isn’t it worth having to endure some personal growth pains to arrive at that outcome?

This French comedy-drama about the trials and tribulations of a foundering author and family man whose life takes an unexpected and quirky turn with his impulsive adoption of a dim-witted, perpetually randy, ever-slobbering dog serves up far more than what its premise would initially seem to offer. What starts off as a frothy farce gradually turns more introspective, providing characters and viewers much to consider, mixed with a wealth of hearty laughs along the way. With fine performances by writer-director Yvan Attal and Charlotte Gainsbourg, this often-hilarious yet thoughtful tale offers more than just another silly rambunctious dog movie, particularly when it comes to assessing our appreciation of what we have – and what we wish we had – as we enter the second half of our lives, a time to make adjustments while we still have the opportunity to get maximum fulfillment and enjoyment during our remaining years. This supremely delightful release is now available for first-run online streaming.

As many of us find out all too late in life, our time in this reality flies by far more quickly than we often realize, especially once we past the apparent midpoint. In light of that, it only makes sense that we don’t fritter away time and energy in unproductive and unsatisfying pursuits. Squandering our resources on undertakings, individuals and efforts that don’t provide a satisfying return simply isn’t wise. But we’re the only ones who can realistically alter what’s amiss. The sooner we get down to that, the sooner we’ll realize the satisfaction we seek, a process that may find us taking some unusual and unexpected steps – some of which, strangely enough, may come at the end of leash. But what those ventures unleash may genuinely astonish us – especially when life finally throws us some long-sought-after bones.

Copyright © 2020, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

Leave A Comment