‘Petrunya’ offers hope where it’s absent

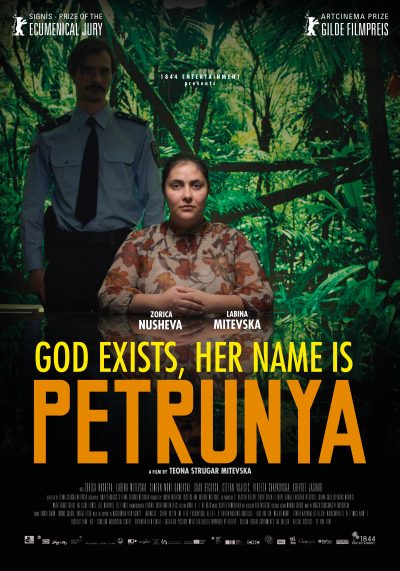

“God Exists, Her Name is Petrunya”(“Gospod postoi, imeto i’ e Petrunija”) (2019 production, 2021 release). Cast: Zorica Nusheva, Labina Mitevska, Simeon Moni Damevski, Suad Begovski-Suhi, Violeta Shapkovska, Petar Mircevski, Andrijana Kolevska, Nikola Kumev, Bajrus Mjaku, Xhevdet Jashari, Stefan Vujisić, Ilija Volcheski, Mario Knezović. Director: Teona Strugar Mitevska. Screenplay: Teona Strugar Mitevska and Elma Tataragic. Web site. Trailer.

When our lives stagnate or don’t turn out as hoped for, we often need a miracle to get on track. Out of cynicism and disbelief, that’s frequently seen as too much to hope for. But, then, all of a sudden, out of the blue, something happens to change all that, completely shifting our outlook and altering the circumstances in our favor. This is particularly beneficial when the stakes are high and many would be affected by a change in fortune. Such is the case in the uplifting and satirical new Macedonian morality play, “God Exists, Her Name is Petrunya”(“Gospod postoi, imeto i’ e Petrunija”).

Life is quite unfulfilling for Petrunya (Zorica Nusheva), a plus-sized, thirty-something unemployed college graduate who still lives at home with her parents, Vaska (Violeta Shapkovska) and Stoyan (Petar Mircevski). She has few prospects for work or for a meaningful social life, and some would say that it’s largely of her own doing, making little effort to improve herself or her lot in life. But, then, it’s not entirely surprising, either, given that she lives in the sleepy little community of Štip, Macedonia, a town with high unemployment levels and few jobs. There are particularly few opportunities for women, given the ensconced patriarchal culture of the former Yugoslav republic. Most women are relegated to comparatively menial jobs, such as garment workers and secretaries, often under the thumb of leering, sexist bosses.

Vaska tirelessly attempts to motivate her daughter to find work and a man, but she unwaveringly clings to the traditional outlook that women are supposed to be subservient to their bosses and husbands. This attitude flies in the face of Petrunya’s views; she’s a liberated free thinker who believes that women should stand up for themselves, even if her own lack of initiative in this regard often leaves something to be desired and undermines her noble contentions. Nevertheless, that doesn’t deter her maternal diehard control freak from trying to push her agenda, nagging Petrunya to get up off her behind and move on with her life instead of perpetually sponging off mom and dad. And, when she learns about an opening for a secretarial position at a nearby garment factory, she cows Petrunya into going for an interview.

Petrunya quickly discovers that her would-be boss (Mario Knezović) is the personification of an unrepentant letch. She leaves the interview disgusted and wanders aimlessly around Štip, trying to collect her thoughts. In the course of her meandering, she comes upon an Orthodox Christian priest (Suad Begovski-Suhi) leading a religious procession and, oddly enough, a group of men dressed only in swim trunks as they move toward the local river. The sight is strange, considering it’s January 19 and decidedly quite cold. However, given that it’s also the Epiphany religious holiday, it’s time for the latest edition of a longstanding tradition, one in which a cross is blessed and tossed into the river. And, once the cross splashes into the water, it’s a signal for all of the eager bathers to jump into the river to retrieve it. The one who is fortunate enough to find it is then said to be blessed with a year’s worth of happiness and good luck. Anyone can participate in this unusual religious sport, provided one condition is met – only men are allowed. But that doesn’t stop Petrunya.

Apparently unaware of the rules of the game, Petrunya impulsively jumps into the river, too. And, as fate would have it, she successfully recovers the cross, much to the amazement of all the onlookers. However, her retrieval of the icon sets off an immediate firestorm. Several male participants, including a particularly angry and vocal contestant (Ilija Volcheski), claim that Petrunya “stole” the cross, despite the fact that she obviously and legitimately came across it first. Before long, disgruntled competitors seek redress from both the priest and police authorities, including Chief Inspector Milan (Simeon Moni Damevski).

Petrunya is soon taken into custody for questioning, even though no formal charges are filed, primarily because no one can stipulate what, if any, laws she has broken. Frequent allegations are leveled against her that she broke “the rules,” but those rules are never fully enumerated (not to mention the fact that rules don’t have the force of law). In true patriarchal fashion, the priest, the inspector, disgruntled participants, and others, including an intimidating interrogator (Nikola Kumev) and potential prosecutor (Bajrus Mjaku), seek to bully Petrunya, gestures that increasingly empower her and galvanize her in her confrontational stance. She continually and aggressively demands to know what she did wrong and why she can’t rightfully retain possession of the cross, requests that repeatedly go unanswered.

As the situation heats up, it draws the attention of the media, most notably an ambitious journalist, Slavica (Labina Mitevska), intent upon raising awareness of Petrunya’s plight (and less than subtly seeking to bolster her own public profile). With her beleaguered cameraman (Xhevdet Jashari) in tow, she covers the story from as many angles as possible, zealously upping the scenario’s feminist message with each televised report.

In no time, the circumstances threaten to spiral out of control. The patriarchal old guard holds firm to its position, even receiving backing from sources like Vaska, who obsequiously and unquestioningly adheres to the view expected of her. Petrunya is virtually on her own, supported only by Slavica, her father and a sympathetic young police officer (Stefan Vujisić). But, the more her foes try to push their position, the more they realize they’re on shaky ground, especially when faced with an intractable adversary who appears to have the force of law on her side. Will Petrunya be able to hold on? Or will her opponents overrun her with threats, intimidation and even outright physical violence? Maybe she’d better hold on to that cross as tightly as she can.

In this day and age, many of us might assume that the sexist attitudes Petrunya faces have disappeared, but, as her experience shows, that’s obviously not the case. Societies that cling to unabashed, inherently biased patriarchal thinking still exist, making life difficult for women who are seeking to advance their status and fulfill aspirations that they believe aren’t in any way restricted by gender. As a consequence, those who feel oppressed have to work harder at making their voices heard to see their objectives realized.

In the face of such opposition, it can be difficult to stay committed. However, those who believe in their cause understand the need to remain focused and ardent in their pursuits. That’s crucial, because our beliefs, thoughts and intents ultimately work to shape what we experience through the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains we draw upon these resources in manifesting the reality around us. A commitment to those notions is thus essential to see those goals materialize.

Petrunya understands this, even if she’s not completely conscious of it, as some of her actions (or lack thereof) demonstrate, primarily before she becomes embroiled in the cross grabbing controversy. That changes, though, once she sees what she can accomplish, despite the relentless criticism she’s grown accustomed to and the oppressive, incessant bullying she experiences at the hands of the sore losers in the race for the icon. She realizes that she can accomplish certain goals, despite what others contend. She believes in herself, and that bolsters her confidence to succeed and to empower herself. She’s not the inferior, incompetent ne’er-do-well that her mother and the men of Štip make her out to be.

Through this experience, Petrunya genuinely begins to tap into the nature and power of her true self, and, with beliefs to back up that newly discovered self, she runs with what she’s found. While some might find her argumentative and gratingly confrontational, she’s actually just fighting for what she believes to be truly and rightfully hers, and who can blame her for that?

That this revelation occurs on the holiday of the Epiphany is a tremendous irony, to be sure. But that irony is actually rooted in Petrunya’s newfound ability to transform her beliefs into manifestations that are in line with her desires and her authentic self. She draws upon the tremendous faith she has quietly come to place in herself, an additional spiritual link to the practical developments that have emerged as a result of this experience. There’s something of an irony in that, too, given that Petrunya generally has had a secular outlook on life, but transformative events like this can do much to reshape one’s existence, both personally and in terms of how they impact the wider world.

While Petrunya seems to have a gradual and modest change of heart about spiritual matters as her story progresses – as evidenced by her mounting desire to retain the cross, something she previously would likely not have cared much about – this development illustrates the significance of divine input in the unfolding of events. As our collaborator in the conscious creation process, the divine spark helps to make possible what we seek to attain. Petrunya may not be consciously aware of this joint alliance, given her views on religion, but it’s present nevertheless, especially in the ways that things develop. There’s a genuineness about this, too, particularly when one witnesses how Petrunya fares in comparison to those who claim to speak for God as definitive authorities on spiritual matters. One could say that, in this context, the film’s title aptly reflects what’s at play in this story.

Based on Petrunya’s experience, as well as the message that Slavica seeks to promote through her broadcasts and the no-nonsense guidance offered by the protagonist’s best friend, Blagica (Andrijana Kolevska), one would likely characterize this movie as a feminist manifesto. However, as an interview with director Teona Strugar Mitevska in the film’s production notes indicates, calling this picture a story exclusively about women’s rights sells it short. Mitevska says that it’s a universal story, one that speaks to the search for justice, fairness and equality, regardless of gender or other defining characteristics. The core beliefs associated with manifesting and promoting these principles are essentially the same, no matter what the underlying issue may be. Petrunya’s efforts at challenging authority figures to seek the implementation of change may be primarily directed at benefitting women, but the process she employs could just as easily be used to better the circumstances of minorities, excluded constituencies or others who face comparable conditions.

Given how this story opens, Petrunya may seem an unlikely candidate to champion a cause such as this. But, then, considering how her life had been unfolding, perhaps she needed a catalyst like this to get her on track. And, in this case, it was one that had a greater purpose behind it, too, one that would benefit not only her, but also others similarly situated. It was as if she were living out her destiny, one that she had not consciously envisaged or anticipated, yet it was one whose impact would be significant and felt by others besides herself. In the process, Petrunya’s undertaking led to the betterment of not only herself, but also others around her, a practice in conscious creation circles known as value fulfillment. In a culture where women are often openly treated as second-class citizens, Petrunya’s righteous defiance sends a powerful signal to those who would support unjustified actions that try to thwart the legitimate aims of others. In the wake of events like this, it’s apparent there truly is a God – and He/She/It has collaborators who help to make initiatives like this possible.

Taking on an entrenched, centuries-old social, religious and political patriarchy is no easy feat, but the protagonist in this pan-European production unwittingly does just that. Director Mitevska’s latest crackles with intensity and biting satire, telling the fact-based story of a 2014 incident involving a similarly situated woman who was proclaimed to be “crazy,” “troubled” and “disturbed.” It delivers an important and empowering message, despite getting bogged down occasionally in repetitive, circular arguments, making the picture come across as a little heavy-handed and dogmatic at times (at least to those of us who reside in more tolerant and open-minded societies). Nevertheless, for a culture that has long fought against progressive social change, perhaps such a sledgehammer approach is what’s needed to get the message across to those who have staunchly resisted it and used whatever means available to them to reinforce such an archaic view against women. To many, it might seem that films like this should no longer be necessary, but the fact that it was made suggests the opposite and that there’s yet more work to be done. Fortunately, “God Exists” does a fine job in that regard. The film has been playing in limited theatrical release and is available for online streaming.

Miracles can work wonders to restore hope, especially when it seems irretrievably lost. They can lift our spirits and restore our faith in the notion that things can work out for us. For those particularly beset by misfortune, that can be a godsend – literally – as Petrunya discovers for herself. But, for these wonders to be truly effective, we must recognize the role we play in their manifestation, developments that wouldn’t occur without our involvement, no matter how much input our divine collaborator supplies. Realizing that is indeed significant, if not a miracle in itself.

Copyright © 2021, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.