‘Bardo’ takes a long, introspective look at life

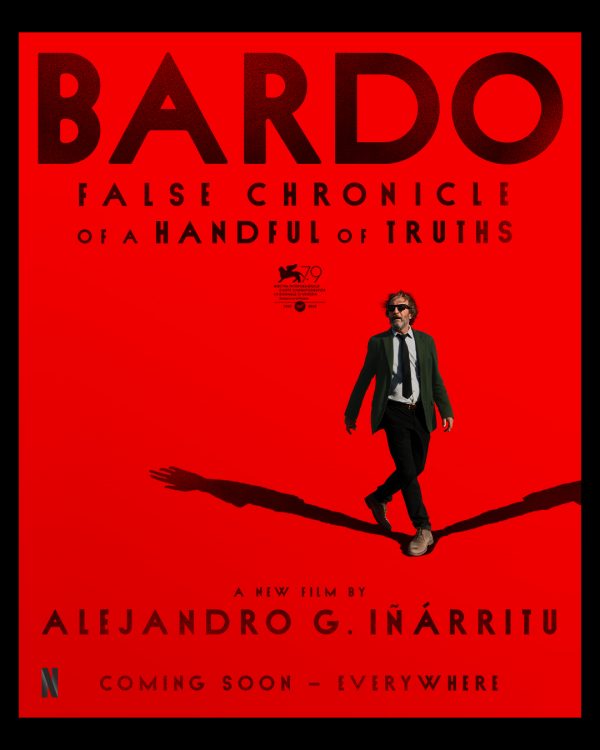

“Bardo: False Chronicle of a Handful of Truths” (“Bardo, falsa crónica de unas cuantas verdades”) (2022). Cast: Daniel Giménez Cacho, Griselda Siciliani, Ximena Lamadrid, Iker Solano, Francisco Rubio, Hugo Albores, Luis Couturier, Luz Jiménez, Jerónimo Guerra, Noé Hernández, Ivan Massagué, Jay O. Sanders, Clementina Guadarrama. Director: Alejandro G. Iñárritu. Screenplay: Alejandro G. Iñárritu and Nicolás Giacobone. Web site. Trailer.

At the same time, however, you also come upon a number of pleasant, unexpected experiences. You hear others paying you glowing compliments and even showering you with accolades. These occurrences, as enjoyable as they are, however, don’t seem to mesh with the other incidents, making you question the disparity, as well as how genuinely deserving you are of the honors being bestowed upon you.

The longer this goes on, the more you come to realize that you’re not in Kansas any more (or, for the protagonist in this story, Mexico). But where exactly are you? That’s the conundrum to be resolved here.

Such are the puzzling circumstances being faced by Silverio Gama (Daniel Giménez Cacho). The respected, late middle-aged journalist and documentary filmmaker is trying to figure out what’s unfolding around him. The Mexican-born broadcaster and auteur has been living in Los Angeles for years after making a name for himself while living south of the border. Once he amassed a bundle of notoriety, however, he headed north with his family to cash in on his marketability, both in terms of the financial and artistic opportunities it afforded him. And cash in he did, taking on a plethora of projects that essentially turned him into a workaholic, a choice that brought him considerable recognition but at a high cost.

As Silverio’s story opens, though, he’s away from his adopted California home, paying a visit to Mexico City, a place he hadn’t visited in years. While there, he has encounters with former colleagues like Carlos (Hugo Albores), Luis (Francisco Rubio) and Hortensia (Clementina Guadarrama), reunions that don’t quite go as planned. He even has some surreal experiences, such as a visit to the city’s historic Chapultepec Castle, a strange occurrence in which past and present appear to collide, leaving the bewildered protagonist and his baffled companion, the US Ambassador to Mexico (Jay O. Sanders), in stunned disbelief.

Silverio next finds himself experiencing what appear to be memories but as viewed from the perspective of his current age. He relives a series of events with his wife, Lucía (Griselda Siciliani), including moments of tenderness, eroticism and disguised tragedy. He engages in a series of conversations with his son, Lorenzo, first as a child (Jerónimo Guerra) and then as a young adult (Iker Solano), discussions that start out pleasant enough but take unexpected left turns, particularly when the talks veer into sociopolitical topics and matters of nationalistic pride. And then there’s the birth of his firstborn, Mateo, a sickly infant who somehow communicates with his mother’s obstetrician that he wants to crawl back into the womb and forego living in the real world, given all its problems, a comically depicted incident that symbolically conceals a darker truth that Silverio has apparently been unable to address.

Silverio’s personal memories are augmented by a review of his highly praised professional accomplishments, such as documentaries about the desperate exodus of migrants travelling northward to seek new opportunities in the US and a profile of an incarcerated drug lord (Noé Hernández) known for his savagery. It raises uneasy feelings for him, especially when he ruminates on the privileged opportunities he’s had in comparison to the lack thereof for most of his fellow countrymen. It also makes him wonder how much he can truly appreciate and adequately depict their experiences given how far removed he has been from them and what they have had to endure. Feelings of hypocrisy creep into his thinking, especially in light of how much he has been applauded by peers and gringos who can’t begin to realistically relate to the experiences of the average Mexican.

Such thoughts emerge in Silverio’s consciousness as he prepares to receive an award from an esteemed American journalism organization, the first foreign-born correspondent to be so honored. Part of him has to wonder whether he’s genuinely worthy of this distinction or whether it’s a move aimed at easing tensions related to US-Mexico immigration policies. In any event, the award presentation is celebrated at a huge, lavish party where Silverio is honored with all of his family members, including Lucía, Lorenzo and the daughter he adores, Camila (Ximena Lamadrid). However, the celebration proves to be a bittersweet affair, one where he’s sufficiently feted by many of his professional colleagues (mostly Americans) and berated by others, such as Luis, who essentially accuses him of being a sell-out to the Mexican journalism community.

Despite the mixed signals Silverio receives from peers, he takes great personal comfort from his family members, who revel in his success and accolades. He even has an opportunity to divert his attention away from the formal festivities to one of a more intimate nature, an encounter with his late father (Luis Couturier). Papá expresses his profound pride in his son’s accomplishments, a moment that’s expressed surrealistically where an adult Silverio is depicted with the stature of a young boy, a symbolic reflection of the nature of his relationship with his dad. A comparably loving encounter with his mother (Luz Jiménez) follows, one that takes him away from the party and gives him pause to start putting together the diversity of experiences he has had thus far.

Additional unusual experiences follow, including a dark, unsettling surrealistic journey to the movie set where Silverio was making a documentary about conquistador Hernan Cortes (Ivan Massagué), a family vacation to Baja California (which, by the way, Amazon has been seeking to purchase, a breaking news story that’s reported on routinely throughout the film), and a return to Los Angeles where an obviously tired Silverio seeks to resume his life and meditate on everything he’s been through of late.

But what does it all mean? Given the far-reaching introspection Silverio has just gone through and the extraordinarily fantastic events he witnessed and experienced, this was far from what one encounters in everyday life. It’s as if he was reliving his life, reviewing it for what it has been, what he might have done differently and who he really is – not what the public, publicists and the world at large say and think about him. If this sounds like something not of this world – especially when it explodes with visions and apparitions none of us typically encounter – you’d be right. And, if you’re wondering where that is, you need only look as far as the film’s title, “Bardo,” the world between worlds that many schools of Buddhist thought maintain we “visit” after passing from the physical plane.

Some might contend that revelation is a spoiler, but that’s an inflated characterization in my view. As noted above, one need only look at the title of the film to see what it’s all about (and, for those who are unfamiliar with the concept of the Bardo, a quick internet search will reveal the answer quickly enough). The more crucial issue at stake here is what do we do with what comes out of a Bardo experience? That’s what Silverio needs to figure out for himself in the wake of what he’s gone through, something that all of us must do after having our own Bardo experiences (or their equivalents as expressed in other spiritual traditions). Of course, determining that we’re having such an experience in the first place is the initial crucial step in this process. It’s something we must all go through in order for the experience to sufficiently grab our attention so that we can focus on and learn from it. Whether we call this process a Bardo experience or a “life review” or whatever other term best suits us, the principle is essentially the same in each case. And that’s what Silverio is now finding out for himself here. The big question, of course, is what will he do with the knowledge he gains from the experience – and takes with him as he moves on to whatever comes next.

But why is Silverio so seemingly confused by what he’s experiencing (at least initially)? There could be a number of reasons. The familiarity of the environment he finds himself in may be so strongly compelling that he might believe he’s still experiencing the physical existence from whence he just came. It’s only when anomalies begin to appear – the surrealistic images, the nonlinear timeline, the examination of issues he rarely if ever contemplated while in physical form – that he begins to suspect that something’s up, nudging him toward considering alternate explanations for what’s transpiring around him.

It should be noted that he’s probably not alone in this, either; many of us may have comparable experiences. This is driven in part by our lack of familiarity with the conscious creation process. Moreover, many of us may have allowed ourselves to have our beliefs conditioned about what to expect after death, frequently a product of religious doctrine. We may have thoroughly convinced ourselves that our afterlife experiences follow circumscribed cookie cutter patterns that we all undergo. But, if the purpose of a life review is to explore the existence we just experienced – one that’s different for each of us based on the beliefs we used to create it – is it realistic to expect that this process of assessment will be identical for all of us? It’s thus easy to see how we might easily become confused when our experience doesn’t jibe with our expectations.

However, if we follow Silverio’s lead, the answers should begin coming to us as we make our way through the experience. When our time in the Bardo begins to mirror where we came from (but in a more candid, more exaggerated form), we’re more likely to piece the puzzle together, just as Silverio does. In many regards, what we experience in the Bardo parallels what we went through in terrestrial existence, but, because the rules of manifestation operate with greater ease, speed and authenticity here than on the physical plane, we begin to see things with greater clarity. We have an opportunity to witness our true selves (and the authentic underlying nature of the life we just lived) with a heightened sense of transparency and lucidity. With the obscuring influence of camouflage now stripped away – an often-hindering force that clouds our beliefs and impacts a true understanding of our existence – we see things through a new set of eyes.

One of the potentially more difficult tasks we might face under these conditions has to do with the matter of judgment. Many of us may be quite surprised when we find that this is yet another afterlife expectation that’s different from what we had allowed ourselves to believe. When we learn that the responsibility for this is placed in our hands, we may be perplexed and overwhelmed. It’s clearly something that Silverio wrestles with as he looks back on his life. For example, he was a good provider for his family, but was he truly an accessible, loving husband and father in light of his workaholic tendencies? Similarly, was he really the sell-out that some of his Mexican professional peers saw him to be? But did their arguably jaded perspective invalidate the heartfelt views of others, like his father, who were genuinely proud of everything he accomplished?

What’s one to make of such seemingly contradictory assessments? Does this mean Silverio would have to repeat certain lessons in his next life to get them “right”? Or did the experiences he had actually live up to what he had intended to go through before incarnating? How does one adequately judge success or failure in circumstances like that? Is that not potentially ambiguous? And what do we do with that information as we prepare to move on to what’s to follow?

These are the kinds of thorny questions that “Bardo” raises, and answers aren’t readily forthcoming. Perhaps that’s because there are no pat, one-size-fits-all resolutions for addressing issues like this, something that many of us may never reflect upon to any significant degree. However, for those of us who are getting on in years, such considerations may cross our minds more readily, and, with the finish line in sight, we may be more tempted to want to prepare ourselves for such an impending eventuality.

“Bardo” is handily the most personal, introspective film that writer-director Alejandro G. Iñárritu has ever made. Perhaps that’s because he ultimately treats the Bardo more as a state of mind than a place, despite the similarity if its earth-like appearance and elements. Through this cinematic vehicle, he delves into a wealth of reflective, heady subjects not unlike those addressed in some of his earlier works, such as “21 Grams” (2003), “Biutiful” (2010) and “Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance)” (2014), as well as similarly themed releases made by other filmmakers, such as Bob Fosse’s “All That Jazz” (1979), Federico Fellini’s “8½” (1963) and Woody Allen’s “Stardust Memories” (1980). It’s also the most flamboyant offering Iñárritu has ever tackled, but that’s not surprising, given that he has a history of making flashy, unconventional movies. And, because of that, it’s easy to see how this release has come to be characterized as a less-than-subtle cinematic autobiography, one that, because of its outrageous nature, has prompted some critics and viewers to label it a self-indulgent vanity project.

But, even if true, is that an inherently bad thing, especially if it gets us thinking? He uses his signature filmmaking style, storytelling approach and singular worldview to examine subjects like personal integrity; relationships with family, friends, colleagues and significant others; regrets and accomplishments; fulfilling one’s potential; and what one might have done differently. In this outing, he takes these familiar themes and their treatment and puts them on steroids, but what better way is there to tackle subjects like these in a setting as innately open-ended and unconstrained as the Bardo? The result is an eye-opening experience for characters and viewers alike.

Admittedly, the picture’s 2:39:00 runtime could have used some judicious pruning (its length having already been scaled back from its even more protracted director’s cut version). That’s especially true for much of the picture’s first hour, which could have been trimmed significantly without losing much (had the director done so, I probably would have given this release an even more glowing recommendation). But, once this release finds its stride, it truly takes off as a great piece of cinema – one that’s inventive, gorgeous to look at and well-acted and that has something to say to boot. What more could a movie lover ask for? Iñárritu really is in his element here, at least for much of the final 90+ minutes, and that’s more than good enough for me. Even though this offering probably won’t appeal to everyone, I’d certainly love to see moviegoers give this one a fair shot. The film is currently playing in limited theatrical release and will be headed to online streaming in the near future.

Copyright © 2022, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.