‘Viking’ stresses the need for flexibility, resourcefulness

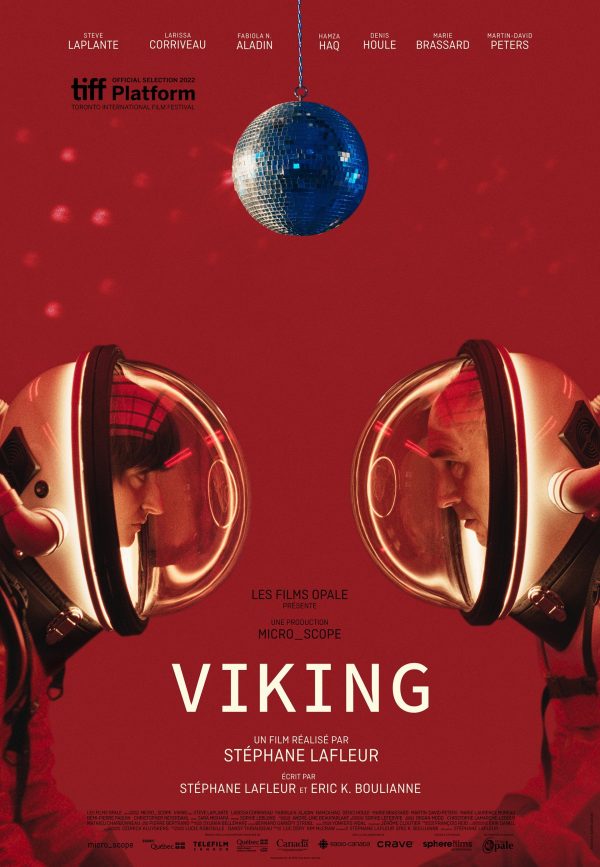

“Viking” (2022 production, 2023 release). Cast: Steve Laplante, Larissa Corriveau, Fabiola N. Aladin, Hamza Haq, Denis Houle, Marie Brassard, Martin-David Peters, Marie-Laurence Moreau, Christopher Heyerdahl, Eric Davis, Mélanie Elliott, Francis Lamarre, Adrienne Richards, Kevin Sin, Sam LaBrie, Spencer Streichert, Paarth Kelkar. Director: Stéphane Lafleur. Screenplay: Eric K. Boulianne and Stéphane Lafleur. Web site. Trailer.

Skip ahead to the present day, as humanity prepares to embark on its first manned mission to the Red Planet. Considering the even greater complexity of this venture – one that, despite extensive crew training, would still need to account for the unpredictable nature of human beings – the space agency decided that it needed to organize a psychological troubleshooting team to address unforeseen issues involving the astronauts, one whose essential mission would be patterned after its technological counterpart established during the Viking missions. It was believed that an Earth-based team of doppelgangers living under conditions similar to their Martian colleagues could be employed as a sort of test kitchen to analyze the problems at hand and to come up with solutions that could be recommended to the space-faring explorers.

Organizers of this undertaking sought to accomplish this by screening applicants whose personalities, likes, interests and character most closely resembled those of the mission members. These metrics were seen as the most important considerations in selecting candidates, with other concerns, like gender and ethnicity, assumed to be secondary. These “surrogates” would stand in for the astronauts as part of the ground-based team, essentially assuming the personas of their Martian colleagues. They were expected to play the parts of the crew members except when being officially debriefed by the organizers. It was a plan that all seemed so very logical and well thought out. However, given the aforementioned unpredictable quality of human nature, could such rational thought realistically be applied in a way that would guarantee success in troubleshooting problems?

As the film opens, the last of the Earth-based screening is under way. The story focuses on David (Steve Laplante), a high school gym teacher who applied for the program as a way to vicariously live out his long-cherished dream of becoming an astronaut. He has been designated as the stand-in for crewman John Shepard (Eric Davis). Joining “John” are his co-horts Steven (Larissa Corriveau, standing in for her Martian counterpart (Francis Lamarre)), Gary (Hamza Haq, standing in for his double (Kevin Sin)), Liz (Denis Houle, standing in for his colleague (Mélanie Elliott)) and crew leader Janet Adams (Fabiola N. Aladin, standing in for the real mission chief (Adrienne Richards)). Supervising the ground crew is the lead organizer, Christiane Comte (Marie Brassard), and her trusty assistant, Jean-Marc (Martin-David Peters). And, after an inspiring motivational speech about the importance of this Earth-based project given by Roy Walker (Christopher Heyerdahl), head of the American space agency in charge of the Mars mission, the five surrogate astronauts are off to their remote desert base to begin their 2½-year task, a momentous occasion for David as he finally realizes the fulfillment (sort of) of a long-held ambition.

The counterparts each live in quarters fitted with a device that prints out a daily briefing noting the mood and condition of his or her Martian colleague. This information, coupled with a summary of issues compiled by Janet, are presented for discussion at a morning breakfast meeting. But David soon finds out that the topics brought up for debate are anything but significant. The five team members discuss mundane matters like one of the crew members (John) flagrantly exceeding his daily sugar ration for use in his morning coffee – two lumps instead of the designated one. And, because David is standing in for John, the onus of coming up with a solution to this Mars-shattering issue is thrust upon him, a situation in which the simulated ridicule of the other astronauts is heaped upon him by their earthly stand-ins. This is followed by similar discussions involving the length of shower times, the promotion of suitable body hygiene and a borrowed but long-unreturned ballpoint pen, issues that get beaten to death during the morning meetings.

David soon begins having doubts about this Earth-bound mission. He speculates that such a disproportionate focus on these kinds of minutiae might be undermining the enthusiasm and effective functioning of their Martian counterparts, a suggestion that’s viewed as supposedly coming “out of character” for what the real John might say. To complicate matters, David begins to think that the criticisms leveled against his ideas are arising directly from the minds of his terrestrial colleagues and not from those of the astronauts they’re supposed to be portraying. In essence, the lines between David and “John” are becoming blurred, as is the case with all of his other earthly associates. He can’t help but wonder, what’s really going on here?

Turning to Christiane and Jean-Marc for guidance provides little clarity. They often communicate in what appears to be a circular, ambivalent form of double-speak. On the one hand, they encourage David to openly express his concerns to them, but, on the other hand, they continually assert his need to stay “in character.” But at what point is he to employ each approach? That’s something that’s not made especially clear. It’s almost as if Christiane, Jean-Marc and everyone else involved in this project are winging it as they go along, and that becomes more apparent the longer the mission goes on – and the issues up for examination and resolution grow progressively more ludicrous and, in some cases, extremely serious. Plan B, it would seem, just doesn’t exist, both for the organizers and their crew, as well as for the astronauts themselves. Devising practical, meaningful answers seems to become progressively more difficult, particularly when the astronauts themselves grow ever more leery of, and resistant to, the proposed solutions.

So what’s to become of all this? That’s hard to say, given that it appears everyone is increasingly flying by the seat of his or her pants, especially when issues related to such matters as leadership, communication, cooperation and staying in character grow ever more dubious and seemingly unsolvable. Will the hoped-for purpose behind the ground crew be fulfilled? Or will it begin to crumble over a lack of focus, guidance and logistics? And what will that mean for the astronauts and ground crew? Stay tuned.

When we embark on such grand planning schemes, we generally approach them from a standpoint of comprehensiveness and inclusivity, with these exercises being tests of our flexibility and resourcefulness to address all of the issues that arise. But what of the overlooked items? Why have such oversights become part of these plans? Perhaps it has to do with the foundation underlying such efforts – a belief that we possess the necessary flexibility and resourcefulness to address whatever issues come our way. However, that thinking implies we already have all the answers in hand, and that conceivably might prompt us to ask ourselves, “How much of a test of our flexibility and resourcefulness is that?” It’s akin to knowing all the questions on an exam before we take it. Is that really a meaningful assessment of our knowledge and wherewithal to solve problems?

If we’re to be truthful with ourselves in testing our abilities in these areas, it would seem that the only fair way to do so is to build in the unexpected up front. When confronted with such unforeseen circumstances, we’re forced into throwing out the rulebook and coming up with innovative approaches to resolving these unplanned-for issues. What’s more, if we’re truly convinced that we’re as flexible and resourceful as we think we are, that means we must also incorporate a belief that maintains we can indeed succeed at such tasks. And that’s important considering the role that our beliefs play in manifesting the reality we experience, a product of the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains we draw upon those intangible resources in materializing our existence.

Understanding this should be inherently crucial to undertaking a task like the one attempted in “Viking.” However, considering how often conditions go awry on so many fronts – both on Earth and Mars – it would seem that the organizers and participants in this venture have overlooked this consideration. While it’s true that they’re often thrust into having to tap into their flexibility and resourcefulness, they often experience assorted errors and conundrums when they do so, suggesting that, on some level, they might not be as sold on their level of expertise as they’d like to think they are. And that kind of intrinsic doubt can torpedo one’s efforts, no matter how seemingly convinced we are of their viability.

It goes without saying that thinking outside the box – surpassing fears, doubts and limitations – is essential in situations like this, especially when far-flung unexpected developments arise. This becomes apparent in the film, for example, when “John” and “Steven” embark on an outdoor assignment involving a Martian ATV in the surrounding terrestrial desert. First, the vehicle gets seriously stuck in the sand. And, while attempting to dislodge it, they have an unexpected encounter with a pair of local cowboys on horseback (Sam LaBrie, Spencer Streichert), a situation assuredly unlike anything the real astronauts might experience. How are the surrogates supposed to handle a scenario like that while remaining in character? (So much for replicating authenticity.)

Then there’s the matter of having to figure out when the Earth-bound crew members are supposed to be “themselves” versus when they’re supposed to stay in character. It’s a question that the organizers don’t seem to have figured out very well. The original plan called for the crew to remain true to the personas of their Martian counterparts at all times except during debriefings, but that plan goes out the window quickly and often, and Christiane and Jean-Marc don’t appear to have any viable solutions for addressing what should be a core component for carrying out this mission.

On top of this, the lack of clarity on this point creates confusion for the ground crew. They’re often left asking themselves, “How far do we take this?” For example, what’s supposed to transpire when a gender-related issue comes up for one of the surrogates who’s portraying a member of the opposite sex? That can be a seemingly insurmountable (and often quite hilarious) predicament for the woman playing Steven and the man playing Liz.

Similarly, what’s to happen when the Earth-based crew receives important news affecting their counterparts, such as developments affecting the well-being of the astronauts’ family members? Do they say something and cause potentially serious disruption of the Mars mission, or do they stay silent on these issues? What’s more, should the surrogates try to come up with solutions for their space-faring colleagues in these situations by staying in character and trying to imagine how their Martian doubles would react? And what if they’re wrong in their assessments and proposed solutions? Couldn’t that lead to devastating psychological harm for those trapped on a faraway planet and unable to get home? Suddenly, these matters don’t seem so funny anymore.

Meaningful solutions could be hard to come by under circumstances like these, especially if the underlying confidence needed to devise them is lacking due to insufficient belief support. This is where the power of discernment comes into play. When faced with such challenges like these, the astronauts, surrogates and organizers (as well as the rest of us for that matter) must learn how to tap into this skill to devise the means for carrying on. This can be tricky enough for those well versed in it, but it’s particularly critical for those who are flying by the seat of their spacesuits, as all these individuals are.

This is an important point for viewers, too, as this aspect of the film serves as a poignant metaphor for audience members. In many regards, the scenes in which the characters are working out their discernment issues serve as potent parables for what those sitting in the theater or in front of their computer screens need to be doing when it comes to resolving such similar matters in their own daily lives. This is especially true when it comes to analyzing the pertinence and relevance of things like official dictates handed down by authority figures, symbolized here by some of the dubious suggestions of the project’s organizers. We all went through our share of this, for example, with the many draconian measures implemented during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. Likewise, we’re seeing this coming through in matters related to free speech on the internet and social media, out-of-control political correctness, and even such areas as what kinds of cars we can drive and what kinds of stoves we can cook on. In essence, these measures are pushing us to assess these conditions and ask ourselves a number of questions: How far are we willing to allow ourselves to go when it comes to these kinds of matters? Are these orders being issued for our genuine well-being, or are they exercises in social conditioning to see how far we can be pushed (and controlled)? And what kind of long-term impact will they have on us, our sense of self and our aptitude for self-determination? That’s quite a lot to think about, especially coming from a comedy.

If nothing else, “Viking” should be seen as a cautionary tale about our need to preserve the means to chart our own paths, lest we lose our ability to ultimately do so. Maintaining that sense of independence, individuality, self-awareness and personal self-confidence is crucial if we hope to manifest the existence of our dreams. And keeping sight of the flexibility and resourcefulness necessary to make that possible can’t be overemphasized enough. Otherwise, our mission just might get scrubbed.

What would you do if you encountered problems while serving as a member of the first mission to Mars? Well, for starters, you’d probably want to watch this movie to figure out what not to do. This comedic what-if offering from writer-director Stéphane Lafleur is one of the most inventive and inspired films I’ve seen in quite some time. Its wry (and sometimes quite dark) humor is simultaneously hilarious, insightful and metaphorical, not to mention astoundingly original, with some of the best writing I’ve come across in ages. The film’s intriguing foundation and telling narrative speak volumes to us on multiple levels (some of which have nothing at all to do with space travel; in fact, one could think of this as a fusion of science fiction and a Stanley Milgram behavioral experiment). All of this is backed up by the picture’s fine performances, superb score, gorgeous photography and outstanding art direction/production design, along with more than a few cinematic homages to such otherworldly classics as “2001: A Space Odyssey” (1968). It’s so heartening to see a film these days that’s highly intelligent, raucously funny, supremely thoughtful and eminently entertaining all at the same time. This feature may not have received much fanfare thus far, but this truly is a picture well worth seeing (thankfully it’s available for streaming on multiple platforms). It’s sure to put you into orbit.

Considering how much “Viking” has going for it, it should come as no surprise that it has received more than its fair share of accolades. The film was nominated for a whopping 10 Canadian Screen Awards, including its achievements in sound editing, sound mixing, art direction/production design, costumes, hair and cinematography (for which it took home the top prize), as well as nods for its original screenplay, director, lead actor (Laplante) and best picture. And, in my view, it was a deserving candidate in all of those categories.

As this film so clearly illustrates, under the right conditions, it can be easy to lose oneself if we’re not vigilant. There’s much at stake if that happens, too, some of which might feel just as emotionally and psychologically devastating as being left out to dry far from home. Confidently preserving our sense of identity, remaining flexible and resourceful, and shrewdly applying our discernment skills can see us through, whether we’re tackling an everyday challenge or participating in a grand extraterrestrial adventure. In either such case, that could truly represent one giant leap for both man and mankind.

Copyright © 2023, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.