‘Lamb’ serves up a morality play down on the farm

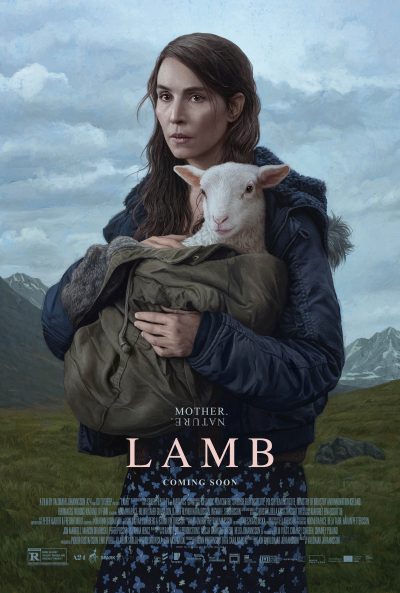

“Lamb” (“Dýrið”) (2021). Cast: Noomi Rapace, Hilmir Snær Guðnason, Björn Hlynur Haraldsson. Director: Valdimar Jóhannsson. Screenplay: Valdimar Jóhannsson and Sjón. Web site. Trailer.

It’s not always easy when it comes to doing the right thing. Then again, there are plenty of instances when it should be patently obvious what we’re supposed to do. But, if that’s really the case, then why do so many of us make questionable choices when confronted with such circumstances? These are among the issues explored in the unusual new, genre-crossing Icelandic offering, “Lamb” (“Dýrið”).

For Maria (Noomi Rapace) and Ingvar (Hilmir Snær Guðnason), an Icelandic farming couple living in the shadow of the North Atlantic island’s remote and imposing mountains, life is rather bleak. They spend their days methodically raising a flock of sheep and planting crops in the rough terrain, going about their work matter-of-factly in a practiced, no-nonsense manner. Beyond that, however, there seems to be little joy in their day-to-day existence, especially when it becomes apparent that the childless couple has experienced a devastating loss, one that they never speak of openly, despite the all-consuming role this tragedy has played in their lives.

With the onset of spring and the start of the lambing season, the mood on the farm lightens somewhat with the arrival of newborns to the herd. Their births bring occasional uncharacteristic smiles to the faces of Maria and Ingvar. They’re especially pleased that the numbers in their flock have increased impressively over previous years. Glimmers of optimism even appear to sprout. But, before long, something unexpected happens, drastically shaking up the couple’s normal routine. In fact, the magnitude of this event is so great that it drastically shakes up life on the farm.

(Note: Those who wish to be surprised about this bombshell should probably stop reading here, because describing its precise nature could conceivably be construed as a spoiler, a practice in which I ordinarily refuse to engage. However, because this development comes so early in the film and impacts its story line from this point onward, it’s fundamentally difficult to summarize this offering without revealing what transpires at this juncture. With that in mind, then, read on at your discretion; otherwise, switch over to one of my many other blogs or three published books.)

As Maria and Ingvar deliver their latest newborn, a shocked look comes over their faces. Viewers aren’t let in on the secret, not only initially, but even for some time thereafter. Nevertheless, it’s quite apparent that there’s something decidedly different about this birth. What’s more, despite the mysterious, almost sinister treatment of this event, Maria and Ingvar seem unexpectedly receptive – almost elated – in response to what’s happened. They’re seen smiling much more often, and they express an unusual amount of care and compassion toward this particular newborn, far more than what they show any of the other new arrivals. They even assume the nurturing process, moving the little one into their home and raising it like a child. But there’s a reason for that: As is eventually revealed, the newborn is, in fact, a lamb-human hybrid, a female whom the couple has named Ada.

With the passage of time, Ada grows and develops, her head and neck being that of a lamb and the remainder of her body assuming the form of a human. Even though she can’t speak in the same manner as her human companions, it’s clear she’s intelligent and comes to understand language just as any child gradually would. She’s able to respond to instructions, walk upright and even express affection toward her adoptive parents. For all practical purposes, Maria and Ingvar treat Ada as their daughter, dressing her in human clothing and treating her like a member of the family. This gives them great joy, the kind that they obviously haven’t experienced for some time.

However, the sanctity of this unconventional household soon becomes threatened on several fronts. For starters, Ada’s birth mother – an evidently aggravated ewe upset that her offspring had been taken away from her – begins exhibiting menacing behavior toward the couple and their trusty herding dog. Maria is particularly troubled by this development and begins weighing her options for how to respond.

Then there’s the unexpected arrival of Ingvar’s brother, Pétur (Björn Hlynur Haraldsson), a down-on-his-luck former musician with a seemingly dubious past. He has a history of periodically showing up when he needs something, like money or a place to stay, accommodations and resources that Maria and Ingvar are willing to trade in exchange for help on the farm. In essence, he truly is the black sheep of this family. But, when he discovers what’s going on with Ada, he’s appalled, looking upon the circumstances as wholly unnatural. When Pétur airs his concerns, Ingvar tells his brother that he’s welcome to stay as long as he wants provided he refrains from interfering in the family’s affairs. He begrudgingly agrees to these terms and eventually even comes to befriend his “niece.” But, despite outward appearances, it’s apparent that he’s also holding something back, as if he’s got a clandestine agenda that he’s looking to play out, and it’s unclear how the fulfillment of his plans might affect Maria, Ingvar and Ada.

With these elements in place, the stage is set for the unfolding of this modern-day fable. How matters transpire will depend on a variety of factors, including some whose seeds have already been sown, some that arise anew, and all of which assume startling and unanticipated forms. Life down on the farm clearly departs from expectations, including those of both the characters and viewers.

No matter how often or how many different ways it may be said, one of life’s truisms maintains that “Actions have consequences.” We may not always like the implications of that. In fact, we may go out of our way to distance ourselves from the fallout of such circumstances, fruitlessly attempting to rationalize the ramifications into oblivion. But, try as we might, they’re there nevertheless, and we ultimately have to deal with them – or face the music of our actions.

Those actions and resulting consequences are the handiwork of our own making, manifestations that emerge into existence as a result of our thoughts, beliefs and intents. This principle is the foundation of the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains we materialize the reality we experience through the power of these intangible resources. And, even though these ethereal, often-imperceptible building blocks may seem patently insubstantial, that’s not to suggest that they have no impact, for they are inherently powerful forces for bringing our existence into being in all of its myriad components – for better or worse.

If we’re to lead peaceful, contented, fulfilling lives, we must never lose sight of this, for, if we do, we may suffer some serious blowback. Employing our thoughts, beliefs and intents to achieve desired goals with no consideration for the consequences can be rife with problems. The unintended side effects alone can be hard to handle once they materialize, potentially making our challenges even more difficult than when we embarked on our manifestation efforts. This is the essence of un-conscious creation (otherwise known as creation by default), a perilous course, to be sure. And, for their part, Maria and Ingvar increasingly face the intricacies and complications of that prospect as events unfold.

It’s common knowledge in conscious creation circles – and just plain common sense elsewhere – that we reap what we sow. We may be able to choose what we wish to create, but we must subsequently accept responsibility for those creations once we bring them into existence, no matter what form those materializations may take. We can’t disavow ourselves from what originated with us. In essence, we can’t unscramble the egg, no matter how hard we may try or how justified we might feel in pursuing such a course in the first place. You can call it karma or payback or any of a number of other terms, but, in the end, the implications are the same in each case.

In many ways, it’s truly perplexing how someone can’t see this when they embark on what is obviously a dubious course. For example, how would Maria and Ingvar feel if a ewe took their child to claim it as her own? As the film so effectively shows in its reaction shots of the mother sheep, we’re not dealing with some dumb, emotionless farm animal here. Like any maternal figure, she has a vested stake in protecting the well-being of her offspring, and it’s not unreasonable to think she would just give up on that obligation, no matter how lovingly her adoptive human parents might treat the newborn.

From the moment Maria and Ingvar decide to start raising Ada as their own, they pursue a course of textbook un-conscious creation. Regardless of what care and compassion they invest in the newborn’s upbringing, their decision to proceed as they do is more about what suits them than anything else. They may believe they’re doing the right thing. They may even feel justified in what they do in light of their own past circumstances. But, in the end, they still fail to ask themselves the core question at the heart of this scenario – are they acting properly and in everyone’s best interests, both for man and beast?

At its heart, “Lamb” is thus a morality play down on the farm, a cautionary tale about the intrinsically intertwined relationship between actions and consequences. It urges us all to think before we act, to avoid the temptation of knee-jerk reactions that may feel good but are questionable at best, to consider the implications of what can result when we pursue a perilously problematic course. This truly is a case where putting thought into our actions up front can save us considerable anguish by failing to do so.

This is not to suggest that the film is all deadly serious drama, however. This deliciously refreshing surprise features an unusual (and I do mean unusual) blend of mystery, horror, folk tale, and dark, offbeat comedy that will easily tickle those whose funny bones lean toward the strange and macabre. Imagine a contemporary story told in the style of a Grimms fairy tale, and you’ve got a pretty good idea what’s in store in this stylish, hilarious, creepy and darkly charming release. Writer-director Valdimar Jóhannsson’s debut feature definitely won’t appeal to everyone, but those who appreciate fresh, inventive material will love this immensely creative offering, told with subtle, tongue-in-cheek wit, gorgeous cinematography and a style that successfully relies more on showing than telling. “Lamb” is further proof that the Icelandic film industry is indeed one of the most innovative on the planet these days, serving up entertaining and thought-provoking offerings that movie communities in other countries could learn a lot from. The film is currently playing in theaters.

Many of us often find ourselves lamenting, “If only life were easier….” Yet there are also times when it seems that condition is met and we still don’t live up to what’s expected of us. In those cases, maybe we need to step back and survey the ethical landscape before us before making any rash decisions that we’ll regret later. Some might see such hesitancy as sheepish; others will see it as prudent – and wise.

Copyright © 2021, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.